George Combe, A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy

of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

ADVERTISEMENT

TO THE

FIFTH EDITION, REVISED.

Since the Fifth Edition of this work was printed, some advances have been made by Physiologists in their researches into the structure of the Brain ; and to present a popular view of these to the reader, the anatomical portion of the work has been revised, and in part rewritten, by James Coxe, M.D., who is known as editor of the works of the late Dr A. Combe. The portions reprinted extend from p. 81 to p. 96, both inclusive; from p. 113 to p. 144, both inclusive ; and from p. *141 to p. *144, both inclusive; the numbers of these last four pages being repeated with an asterisk to adapt them to page 145. The rest of the First and Second Volumes continues unaltered, no changes requiring notice having, as far as I am aware, taken place in Phrenology since they were printed.

The present stationary condition of the science

viii ADVERTISEMENT.

appears to me to arise from the circumstance that the individuals who first introduced it to the world, and also their coadjutors in elucidating, extending, and diffusing it, are either dead or so far advanced in life as to be no longer capable of new investigations ; while the body of facts and deductions which they have published have been, and still are, not only far "in advance of public opinion, but so imperfectly known to and appreciated by the class which labours to extend the boundaries of science, that fewer motives are presented to young men to cultivate this particular field, than to prosecute other more popular departments of investigation. The only advance which, in these circumstances, could be expected, has actually occurred, namely, a wider diffusion of a knowledge of Phrenology, and a juster estimate of its merits among the people at large. Its influence is now discernible in general literature, and in educational and other reforms.

45 MELVILLE STREET, EDINBURGH, 1853.

PREFACE

TO THE

SECOND EDITION.

THE following are the circumstances which led to the publication of the present Work.

My first information concerning the system of Drs Gall and Spurzheim, was derived from No. 49. of the Edinburgh Review. Led away by the boldness of that piece of criticism, I regarded the doctrines as contemptibly absurd, and their authors as the most disingenuous of men. In 1816, however, shortly after the publication of the Review, my friend Mr Brownlee invited me to attend a private dissection of a recent brain, to be performed in his house by Dr Spurzheim. The subject was not altogether new, as I had previously attended a course of demonstrative lectures on Anatomy by Dr Barclay. Dr Spurzheim exhibited the structure of the brain

ii PREFACE.

to all present (among whom were several gentlemen of the medical profession), and contrasted it with the bold averments of the Reviewer. The result was a complete conviction in the minds of the observers, that the assertions of the Reviewer were refuted by physical demonstration.

The faith placed in the Review being thus shaken, I attended the next course of Dr Spurzheim's lectures, for the purpose of hearing from himself a correct account of his doctrines. The lectures satisfied me, that the system was widely different from the representations given of it by the Reviewer, and that, if true, it would prove highly important ; but the evidence was not conclusive. I therefore appealed to Nature by observation ; and at last arrived at complete conviction of the truth of Phrenology.

In 1818, the Editor of the " Literary and Statistical Magazine for Scotland," invited me to a free discussion of the merits of the system in his work, and I was induced to offer him some essays on the subject. The notice which these attracted led to their publication in 1810, in a separate volume, under the title of " Essays on Phrenology." A second edition of these Essays has since been called for, and the present volume is offered in compliance with that demand. In the present work, I have adopted the title of " A System of Phrenology," on account of

PREFACE. iii

the wider scope, and closer connexion, of its parts ; but pretend to no novelty in principle, and to no rivalry with .the great founder of the science.

The controversial portions of the first edition are here almost entirely omitted. As the opponents have quitted the field, these appeared no longer necessary, and their place is supplied by what I trust will be found more interesting matter. Some readers may think that retributive justice required the continued republication of the answers to the attacks of the opponents, that the public mind, when properly enlightened, might express a just disapprobation of the conduct of those who so egregiously misled it : but Phrenology teaches us forbearance ; and, besides, it will be misfortune enough to the individuals who have distinguished themselves in the work of misrepresentation, to have their names handed down to posterity, as the enemies of one of the most important discoveries ever communicated to mankind.

In this work, the talents of several living characters are adverted to, and compared with the development of their mental organs,-which is a new feature in philosophical discussion, and might, without explanation, appear to some readers to be improper : But I have founded such observations on the printed works, and published lusts or casts, of the

iv PREFACE.

individuals alluded to ; and both of these being public property, there appeared no impropriety in adverting to them. In instances in which reference is made to the cerebral development of persons whose busts or casts are not published, I have ascertained that the observations will not give offence.

1825.

PREFACE

TO THE

FIFTH EDITION.

A STRIKING change has taken place in public opinion in regard to Phrenology since October 1819, when the first edition of this work appeared. Then, Phrenology and Phrenologists were assailed with every species of ridicule, and held in such contempt that few opponents considered it necessary to meet their statements either by adverse facts or by arguments. Now, a general impression prevails that there is more or less of truth in the doctrines, and that they merit a serious investigation. This opinion has been partly formed, and certainly is strongly supported, by the advocacy of the new views by three of the most influential Medical Journals of Great Britain. From an early date, Phrenology has been fully expounded, and its leading principles defended, in the Medico-Chirurgical Review and the London Lancet ; and more recently by the British

vi PREFACE.

and Foreign Medical Review.* With such aids, its eventual triumph over the still lingering prejudices of a part of the British public may be safely predicted. Nor has its progress in foreign countries been less satisfactory. In France, in the United States of America, and in Italy, the press affords evidence of the steady advance of the science; while in Germany also, where it was supposed to be extinct (but where, in point of fact, it scarcely had an existence beyond the persons of Drs Gall and Spurzheim, who left that country more than thirty years ago), it has at last taken root, and is diffused through the medium of a recently instituted German Phrenological Journal, and by a variety of individual treatises on its doctrines and applications. The fifth edition of this work, therefore, is presented to the public with less anxiety regarding the spirit in which it will be received than were any of its predecessors; but there is one preliminary point on which I consider it necessary to offer a few remarks.

I define Science to be a correct statement, methodically arranged, of facts in nature accurately observed, and of inferences from them logically deduced ; and add, that there is a difference between

* Vol. IX. No. 17, and Vol. XIV. p. 65.

PREFACE. vii

science and established science. When Newton published his discoveries regarding the composition of light, he recorded scientific truth; but his statements were at first denied and opposed ; next they were discussed and tested ; and it was only after a number of individuals, commanding public confidence by their talents and attainments, had concurred in testifying to their truth, that they were admitted as established. From the first, they were established in nature, but not in human opinion. The more difficult of proof a science is, the longer will be the time which will elapse before it is admitted as established.

Phrenology is not an exact, but an estimative science. It does not resemble mathematics, or even chemistry, in which measures of weight and number can be applied to facts ; but, being a branch of physiology, it, like medical science, rests on evidence which can be observed and estimated only. We possess no means of ascertaining, in cubic inches, or in ounces, the exact quantity of cerebral matter which each organ contains, or of computing the precise degree of energy with which each faculty is manifested ; we are able only to estimate through the eye and the hand the one, and by means of the intellect the other. It is true that when cases of large size and extreme deficiency in particular or-

viii PREFACE.

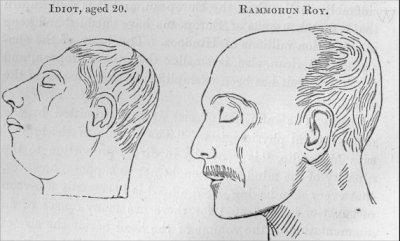

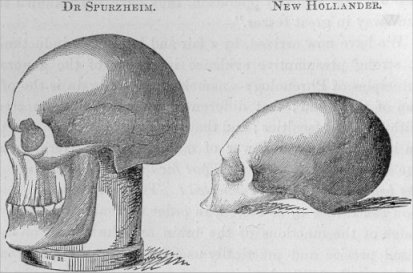

gans are selected as the tests of the truth of Phrenology, the differences are so palpable, that no observer, of ordinary acuteness, can fail to perceive them, nor can he, in such instances, easily mistake the degree of power with which the corresponding faculties are manifested. But still this evidence, palpable as it is, can be obtained by means only of observation and reflection, and cannot be substantiated by measurements of quantity and number.

This circumstance renders the value attached by inquirers to the reported evidence in favour of Phrenology dependent on their estimate of the talents of the reporter for accurate observation, for correct inference, and for faithful relation. Hence, although Phrenology may be a correct representation of truths existing in nature, and in this respect may actually be a science ; yet, from prejudice in the public mind, as well as from difficulties attending the evidence, it may be regarded by many as not yet an established science.

The history of science, indeed, shews that important discoveries have been rejected, and the discoverers opposed and ridiculed by their contemporaries, even in instances in which the truth of the new propositions was susceptible of ocular or mathema-

PREFACE. ix

tical demonstration. We cannot, therefore, reasonably be surprised that some individuals object to the evidence in favour of Phrenology, recorded in this and other works, as not being sufficient to produce in their minds conviction of its truth. To such persons I respectfully suggest, that, if the recorded evidence be not to them satisfactory, they should appeal to nature. Phrenologists do not rest the truth of the science solely on reported cases ; they do not affirm that the existing recorded evidence is sufficient to force the assent of all minds ; but state, that, in order to obtain philosophical conviction, the inquirer who doubts should resort to personal observations. Dr Spurzheim (in his Outlines, p. 222) very early said, " I again repeat, that I could here speak only of the results of the immense number of facts which we have collected. Several may complain of my not mentioning a greater number of those facts ; but in reply, I need only answer, that, were I to write as many books of cases as there are special organs, still no one could, on this subject, attain personal or individual conviction, before he had practically made the same observations. I may further remark, that the detailed narrative of a thousand cases, would not improve the science, more than that of a few characteristic ones, which state our meaning, and shew

x PREFACE.

what is to be observed, and how we are to observe. Self-conviction can be founded only on self-observation ; and this cannot be supplied by continually reading similar descriptions of configuration. Such a proceeding may produce confidence, but not conviction. This requires the actual observation of nature."

In regard to the means of proof, Phrenology does not differ materially from some of the other sciences. The testimony of its supporters to points of fact must be either received or rejected by the student : If he reject it as insufficient, he is entitled to suspend his belief, but not to deny the truth of what is asserted. If he wish to obtain positive conviction that it is true or false, no course is open to him except to resort to personal observation.

I confess that I was one of those who regarded the cases reported by Dr Spurzheim as not furnishing sufficient evidence of the truth of Phrenology ; but I acted according to his suggestion, and used them as guides to direct my own investigations. To obtain conviction, I made a direct appeal to nature. At first I found it difficult to discriminate the situations of the different organs, to estimate their relative proportions, to distinguish the manifestations

PREFACE. xi

of particular faculties, and to judge of the degrees of their energy; but I perceived that difficulties of the same kind beset the student of medicine, and that no man had ever learned to distinguish diseases, to form accurate diagnosis and prognosis of them, by merely reading descriptions and reported cases of their treatment and cure. As the medical student learns anatomy only by the patient and direct application of his eye and hand to the structure of the body, and acquires skill in practical medicine only by resorting to the sick-beds of public hospitals and private families, so I saw that it was only by applying the hand and the eye to distinguish the situations and relative magnitudes of the cerebral organs, and by observing, in active life, the mental manifestations, that I could hope to become really skilled in Phrenology ; and I followed this course accordingly. The result, after falling into many errors, and surmounting numerous difficulties, was the attainment of a deep conviction of the truth and importance of the doctrines, and it was only after reaching this point, that I became acquainted with the writings of Dr Gall.

But, as I had regarded in this light the facts reported by Dr Spurzheim, I could not, in consistency with reason, wish or expect that future inquirers

xii PREFACE.

should view the cases reported by me as sufficient to supply the desideratum. I, therefore, mentioned them in the same spirit, and with the same objects, as those avowed by Dr Spurzheim in the foregoing quotation. This, however, in several instances has not been understood : While some individuals have, without hesitation, embraced Phrenology on the faith of the reported cases ; others, also actuated by a sincere desire to arrive at truth, have complained of the insufficiency of this evidence to produce a scientific conviction in their minds, and they have in consequence objected to the statement as unwarranted, that certain of the organs are " regarded as established." I beg leave to explain, that by this expression I mean, that the evidence which I have met with has produced the conviction in my own mind that the organs are established in nature ; but I do not intend to affirm, that the facts and arguments adduced in this work, are of themselves sufficient to establish the reality of the organs to the satisfaction of every reader. In these circumstances, no better means of advancing the cause occurs to me, than to request every one in whom the recorded evidence fails to produce conviction, to resort to actual observation in the great field of nature.

I am aware of the unfavourable reception which

PREFACE. xiii

this request will meet with from the inquirer whose practice it is to sit in his library and read reports of scientific experiments and observations, to submit them to the searching analysis of a critical logic, and to admit or reject them, and the conclusions deduced from them, according to the results of this investigation. Such a person shrinks from examining heads, as a vulgar and ludicrous occupation; and from mingling in the din of busy life, as annoying to his habits of retirement, and distracting to his attention. He insists not only on trying Phrenology solely by the reported cases, but on including all who call themselves Phrenologists in the list of the witnesses on whose testimony he is entitled to decide. Nay, further, he considers himself authorized, on the result of this scrutiny, not only to suspend his belief, but positively to deny the truth of the whole, or of a greater or smaller portion of the doctrines. As reasonably might a scientific inquirer pass sentence on the value of Medical Science after merely reading the works of physicians, and studying cases reported by the most cautious practitioners and the most ignorant and unprincipled quacks, and assigning to them all an equal value.

Again, other inquirers, who have proceeded a cer -

xiv PREFACE.

tain length in making direct observations, have admitted, as ascertained,-some of them, the three great divisions of the brain into the organs of the animal propensities, the moral sentiments, and the intellectual faculties ;-others of them, not only these, but the functions of several of the larger individual organs ;-while they have dogmatically rejected all the other subdivisions, as unsupported by sufficient evidence. There are individuals, also, who deny the adequacy of the evidence to prove particular organs, which in their own brains are so small, that they experience great difficulty in comprehending the functions assigned to them. To such objectors I can reply only, in the words of Dugald Stewart, that the point reached by the end of their own sounding-line is not necessarily the bottom of the ocean. In 1819, the public, by almost universal acclamation, denounced the whole doctrines of Phrenology as sheer quackery and nonsense ; seven years afterwards, some influential individuals and public Journals admitted that there was some truth in the principles on which Phrenology was based ; after other seven years, the same authorities acknowledged that the division of the brain into the three great regions before mentioned, seemed to be supported by considerable evidence ; and at the close of a third period of seven

PREFACE. xv

years, many competent judges admit that there are satisfactory proofs for several of the larger organs. During all this time, there has been no restriction of the limits, and no important variation in the doctrines, of Phrenology : The change that has taken place has been in public opinion ; and it has arisen from the greater degree of attention with which the public, or the individuals whom it recognises as its guides, have devoted themselves to the study of the principles, and to the observation of the facts, on which the doctrines are founded. Nor will this onward progress stop at its present point : I rest confident, that, at the end of the next seven years, still more of the details will be admitted to be true. Indeed, it appears to me, that the great facts and inductions of Phrenology, like those of many other sciences, will be ultimately received into the category of established truths, not in consequence of any rigidly scientific demonstration presented in the form of recorded evidence, but by general acquiescence, founded on the testimony of men on whose talents, judgment, and opportunities of observation, public reliance will be placed.

Far from either denying or undervaluing the importance of accurately reported evidence as a means of advancing the doctrines to the rank of an ES-

PREFACE. xvi

TABLISHED science, I desire to see this testimony increased ; but in the mean time I respectfully maintain, that Phrenology does contain a goodly array of correctly observed facts, and justly drawn conclusions, and that in this sense it is actually a science. I do not, however, condemn those who affirm that, from the paucity of well-qualified observers and reporters, it is not yet established in their opinion : all I urge is, that such persons are not entitled to deny the truth of the phrenological facts and inferences, but only to suspend their own judgment until they shall have resorted to personal observations.

Although I am far from asserting, for Phrenologists or myself, freedom from inaccuracy in observation and from error in induction, and farther still from deprecating the most rigid scrutiny into the cases which I have reported ; yet I do venture to say, that any inquirer, who will proceed, patiently and without bias, to interrogate Nature, and to observe cases of great size and marked deficiency in the development of individual organs (which afford the most certain and unequivocal proofs), will find the phrenological conclusions to be drawn with a degree of accuracy equal at least to that which is presented by other sciences that have been culti-

PREFACE. xvii

vated only for the same length of time, and which depend for their advancement on the observation and estimation of complicated natural phenomena*

Large additions have been made to the present edition ; some new plates and cuts are given ; and, in treating of topics of interest, I have added references to other phrenological works in which they are discussed or illustrated, so as to render this -edition an index, as far as possible, to the general literature of the science. The Appendix contains Testimonials in favour of the truth of Phrenology, and of its utility in the classification and treatment of criminals, presented in February 1836 by Sir George S. Mackenzie, one of the earliest and most zealous advocates of the science, to Lord Glenelg, Secretary for the Colonies. His Lordship subsequently transmitted the documents to Lord John Russell, Secretary for the Home Department, who promised to Sir George to bestow on them due consideration ; but up to the present time no movement has taken place on the subject. As truth cannot

* See an article on " The Nature of the Evidence by which the Functions of different parts of the Brain may be established," in the Phrenological Journal, vol. x. p. 556 ; and in " Gall on the Cerebellum," p. 181 ; also, the Phren. Journ,, vol. xii. p. 150, 346-7 ; vol. xiii. p. 97, 339 ; and vol. xiv. p. 4, 343.

b

xviii PREFACE.

die, I have been requested to continue the circulation of these documents along with the present edition, in the expectation that sooner or later they will lead to practical results.

Dr Spurzheim, in the American Edition of his " Phrenology," published at Boston in 1832, adopted a new arrangement of the organs, different from any which he had previously followed. It will be impossible, however, to arrive at a perfect classification and numeration of the organs until the whole of them shall have been discovered, and the primitive or elementary faculties shall have been ascertained. Any order, therefore, adopted in the mean time, must be to some extent arbitrary. Dr Spurzheim has shewn this to be the case by the frequent alterations which he has made in the numeration of the organs, without having added any corresponding discoveries to the science. The difficulties attending a correct classification are stated in the Appendix, No. II., and for the present I retain, as a matter of convenience, the order followed in the third and fourth editions of this work.

EDINBURGH, 31st March 1843.

A

SYSTEM

of

PHRENOLOGY

_____

INTRODUCTION.

PHRENOLOGY, (derived from the Greek word ...., mind, and λογς, discourse,) professes to be a system of Philosophy of the Human Mind, founded on the physiology of the brain. It was first offered to public consideration on the continent of Europe in 1796, but in Britain was almost unheard of till the year 1815. It has met with strenuous support from some individuals, and determined opposition from others ; while the great body of the public remain uninstructed as to its merits. On this account, it may be useful to present, in an introductory form, 1st, A short notice of the reception which other discoveries have met with on their first announcement ; 2dly, A brief outline of the principles involved in Phrenology; 3rdly, An inquiry into the presumptions for and against these principles, founded on the known phenomena of human nature ; and, 4thly, An historical sketch of the discovery of the organs of the mind.

I shall follow this course, not with a view of convincing the reader that Phrenology is true, (because nothing short of patient study and extensive personal observation can produce this conviction,) but for the purpose of presenting him

2 OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERIES.

with motives to prosecute the investigation for his own satisfaction.

First, then-one great obstacle to the reception of a discovery is the difficulty which men experience in at once parting with old notions which have been instilled into their minds from infancy, and become the stock of their understandings. Phrenology has encountered this impediment, but not in a greater degree than other discoveries which have preceded it. Locke, in speaking of the common reception of new truths, says : " Who ever, by the most cogent arguments, will be prevailed with to disrobe himself at once of all his old opinions and pretences to knowledge and learning, which with hard study he hath all his time been labouring for, and turn himself out stark naked in quest afresh of new notions'? All the arguments that can be used, will be as little able to prevail as the wind did with the traveller to part with his cloak, which he held only the faster." 1

Professor Playfair, in his historical notice of discoveries in physical science, contained in the third Preliminary Dissertation in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, observes, that " in every society there are some who think themselves interested to maintain things in the condition wherein they have found them. The considerations are indeed sufficiently obvious, which, in the moral and political world, tend to produce this effect, and to give a stability to human institutions, often so little proportionate to their real value or to their general utility. Even in matters purely intellectual, and in which the abstract truths of arithmetic and geometry seem alone concerned, the prejudices, the selfishness, or vanity of those who pursue them, not unfrequently combine to resist improvement, and often engage no inconsiderable degree of talent in drawing back, instead of pushing forward, the machine of science. The introduction of methods entirely new must often change the relative place of the men engaged in scientific pursuits ; and must oblige many, after descending from the stations they formerly oc-

1 Locke On the Human Understanding, b. iv. c. 20, sect. 11.

OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERIES. 3

cupied, to take a lower position in the scale of intellectual advancement. The enmity of such men, if they be not animated by a spirit of real candour, and the love of truth, is likely to be directed against methods by which their vanity is mortified, and their importance lessened." '

Every age has afforded proofs of the justness of these observations. " The disciples of the various philosophical schools of Greece inveighed against each other, and made reciprocal accusations of impiety and perjury. The people, in their turn, detested the philosophers, and accused those who investigated the causes of things of presumptuously invading the rights of the Divinity. Pythagoras was driven from Athens, and Anaxagoras was imprisoned, on account of their novel opinions. Democritus was treated as insane by the Abderites for his attempts to find out the cause of madness by dissections ; and Socrates, for having demonstrated the unity of God, was forced to drink the juice of hemlock." *

But let us attend in particular to the reception of the three greatest discoveries that have adorned the annals of philosophy, and mark the spirit with which they were hailed.

Mr Playfair, speaking of the treatment of Galileo, says :- " Galileo was twice brought before the Inquisition. The first time, a council of seven cardinals pronounced a sentence which, for the sake of those disposed to believe that power can subdue truth, ought never to be forgotten : viz. That to maintain the sun to be immoveable, and without local motion, in the centre of the world, is an absurd proposition, false in philosophy, heretical in religion, and contrary to the testimony of Scripture ; and it is equally absurd and false in philosophy to assert that the earth is not immoveable in the centre of the world, and, considered theologically, equally erroneous and heretical." The following extract from Galileo's Dialogue on the Copernican

1 Encydapodia, Britannica, 7th edit. i. 533.

2 Dr Spurzheim's Philosophical Principles of Phrenology. London 1825, p. 96.

4 OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERIES.

System of Astronomy, shews, in a very interesting manner how completely its reception was similar to that of Phrenology.

" Being very young, and having scarcely finished my course of philosophy, which I left off as being set upon other employments, there chanced to come into those parts a certain foreigner of Rostoch, whose name, as I remember, was Christianus Urstitius, a follower of Copernicus, who, in an academy, gave two or three lectures upon this point, to whom many flocked as auditors ; but I, thinking they went more for the novelty of the subject than otherwise, did not go to hear him : for I had concluded with myself that that opinion could be no other than a solemn madness ; and questioning some of those who had been there, I perceived they all made a jest thereof, except one, who told me that the business was not altogether to be laughed at : and because the man was reputed by me to be very intelligent and wary, I repented that I was not there, and began from that time forward, as oft as I met with any one of the Copernican persuasion, to demand of them if they had been always of the same judgment. Of as many as I examined, I found not so much as one who told me not that he had been a long time of the contrary opinion, but to have changed it for this, as convinced by the strength of the reasons proving the same ; and afterwards questioning them one by one, to see whether they were well possessed of the reasons of the other side, I found them all to be very ready and perfect in them, so that I could not truly say that they took this opinion out of ignorance, vanity, or to shew the acuteness of their wits. On the contrary, of as many of the Peripatetics and Ptolomeans as I have asked (and out of curiosity I have talked with many) what pains they had taken in the book of Copernicus, I found very few that had so much as superficially perused it, but of those who I thought had understood the same, not one : and, moreover, I have inquired amongst the followers of the Peripatetic doctrine, if ever any of them had held the contrary opinion, and likewise found none that

OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERT 5

had. Whereupon, considering that there was no man who followed the opinion of Copernicus that bad not been first on the contrary side, and that was not very well acquainted with the reasons of Aristotle and Ptolemy, and, on the contrary, there was not one of the followers of Ptolemy that had ever been of the judgment of Copernicus, and had left that to embrace this of Aristotle ;-considering, I say, these things, I began to think that one who leaveth an opinion imbued with his milk and followed by very many, to take up another, owned by very few and denied by all the schools, and that really seems a great paradox, must needs have been moved, not to say forced, by more powerful reasons. For this cause I became very curious to dive, as they say, into the bottom of this business."

It is mentioned by Hume, that Harvey was treated with great contumely on account of his discovery of the circulation of the blood, and in consequence lost his practice. An eloquent writer in the 94th Number of the Edinburgh Review, when speaking of the treatment of Harvey, observes, that " the discoverer of the circulation of the blood-a discovery which, if measured by its consequences on physiology and medicine, was the greatest ever made since physic was cultivated-suffers no diminution of his Reputation in our day, from the incredulity with which his doctrine was received by some, the effrontery with which it was claimed by others, or the knavery with which it was attributed to former physiologists by those who could not deny and would not praise it. The very names of these envious and dishonest enemies of Harvey are scarcely remembered ; and the honour of this great discovery now rests, beyond all dispute, with the great philosopher who made it." This shews that Harvey, in his day, was treated exactly as Dr Gall has been in ours ; and if Phrenology be true, these or similar terms may one day be applied by posterity to him and his present opponents.

Again, Professor Playfair, with reference to the discovery of the composition of light by Sir Isaac Newton, says :

6 OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERIES,

" Though the discovery now communicated had every thing to recommend it which can arise from what is great, new, and singular ; though it was not a theory or a system of opinions, but the generalization of facts made known by experiments ; and though it was brought forward in the most simple and unpretending form ; a host of enemies appeared, each eager to obtain the unfortunate pre-eminence of being the first to attack conclusions which the unanimous voice of posterity was to confirm. . . . Among them one of the first was Father Pardies, who wrote against the experiments, and what he was pleased to call the hypothesis, of Newton. A satisfactory and calm reply convinced him of his mistake, which he had the candour very readily to acknowledge. A countryman of his, Mariotte, was more difficult to be reconciled, and, though very conversant with experiment, appears never to have succeeded in repeating the experiments of Newton."1 ' A farther account of the hostility with which Newton's discoveries were received by his contemporaries, will be found in his Life by Brewster, p. 171.

Here, then, we see that persecution, condemnation, and ridicule, awaited Galileo, Harvey, and Newton, for announcing three great scientific discoveries. In mental philosophy the conduct of mankind has been similar.

Aristotle and Descartes " may be quoted, to shew the good and bad fortune of new 'doctrines. The ancient antagonists of Aristotle caused his books to be burned ; but in the time of Francis I. the writings of Ranrus against Aristotle were similarly treated, his adversaries were declared heretics, and, under pain of being sent to the galleys, philosophers were prohibited from combating his opinions. At the present day, the philosophy of Aristotle is no longer spoken of. Descartes was persecuted for teaching the doctrine of innate ideas ; he was accused of atheism, though he had written on the existence of God ; and his books were burned by order of the University of Paris. Shortly after-

1 Encyc. Brit. i. 551.

OPPOSITION TO DISCOVERIES. 7

wards, however, the same learned body adopted the doctrine of innate ideas ; and when Locke and Condillac attacked it, the cry of materialism and fatalism was turned against them. Thus the same opinions have been considered at one time as dangerous because they were new, and at another as useful because they were ancient. What is to be inferred from this, but that man deserves to be pitied ; that the opinions of contemporaries on the truth or falsehood, and the good or bad consequences, of a new doctrine, are always to be suspected ; and that the only object of an author ought to be to point out the truth."1

To these extracts many more might be added of a similar nature ; but enough has been said to demonstrate, that, by the ordinary practice of mankind, great discoveries are treated with hostility, and their authors with hatred and contempt, or at least with neglect, by the generation to which they are originally published.

If, therefore, Phrenology be a discovery at all, and especially if it be also important, it must of necessity come into collision, on the most weighty topics, with the opinions of men hitherto venerated as authorities in physiology and the philosophy of mind ; and, according to the custom of the world, nothing but opposition, ridicule, and abuse, could be expected on its first announcement. If we are to profit, however, by the lessons of history, we ought, after surveying these mortifying examples of human weakness and wickedness, to dismiss from our minds every prejudice against the subject before us, founded on its hostile reception by men of established reputation of the present day. He who does not perceive that, if Phrenology shall prove to be true, posterity will regard the contumelies heaped by the philosophers of this generation on its founders as another dark speck in the history of scientific discovery,-and who does not feel anxious to avoid all participation in this ungenerous treatment,-has reaped no moral improvement from the re-

1 Dr Spurzheim's Philosophical Principles of Phrenology, p. 97.

8 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

cords of intolerance which we have now contemplated : But every enlightened individual will say, Let us dismiss prejudice, and calmly listen to evidence and reason ; let us not encounter even the chance of adding our names to the melancholy list of the enemies of mankind, by refusing, on the strength of mere prejudice, to be instructed in the new doctrines submitted to our consideration ; let us inquire, examine, and decide.

These, I trust, are the sentiments of the reader ; and on the faith" of their being so, I shall proceed, in the second place, to state very briefly the principles of Phrenology.

It is a notion inculcated-often indirectly no doubt, but not less strongly-by highly venerated teachers of intellectual philosophy, that we are acquainted with Mind and Body as two distinct and separate entities. The anatomist treats of the body, and the logician and moral philosopher of the mind, as if they were separate subjects of investigation, either not at all, or only in- a remote and unimportant degree, connected with each other. In common society, too, men speak of the dispositions and faculties of the mind, without thinking of their close connexion with the body.

But the human mind, as it exists in this world, cannot, by itself, become an object of philosophical investigation. Placed in a material world, it cannot act or be acted upon, but through the medium of an organic apparatus. The soul sparkling in the eye of beauty transmits its sweet influence to a kindred spirit only through the filaments of an optic nerve ; and even the bursts of eloquence which flow from the lips of the impassioned orator, when mind appears to transfuse itself almost directly into mind, emanate from, and are transmitted to, corporeal beings, through a voluminous apparatus of organs. If we trace the mind's progress from the cradle to the grave, every appearance which it presents reminds us of this important truth. In earliest life the mental powers are feeble as the body ; but when manhood conies, they glow with energy, and expand with power ; till

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND. 9

at last the chill of age makes the limbs totter, and the fancy's fires decay.

Nay, not only the great stages of our infancy, vigour, and decline, but the experience of every hour, remind us of our alliance with the dust. The lowering clouds and stormy sky depress the spirits and enerve the mind ;-after short and stated intervals of toil, our wearied faculties demand repose in sleep ;-famine or disease is capable of levelling the proudest energies with the earth ;-and even the finest portion of our compound being, the Mind itself, apparently becomes diseased, and, leaving nature's course, flies to self-destruction to escape from wo.

These phenomena must be referred to the organs with which, in this life, the mind is connected : but if the organs exert so great an effect over the mental manifestations, no system of philosophy can be looked on as complete, which neglects their influence, and treats the thinking principle as a disembodied spirit. The phrenologist, therefore, regards man as he exists in this world ; and desires to investigate the laws which regulate the connexion between the mind and its organs, but without attempting to discover the essence of either, or the manner in which they are united.

The popular notion, that we are acquainted with mind unconnected with matter, is therefore founded on an illusion. In point of fact, we do not in this life know mind as one entity, and body as another ; but we are acquainted only with the compound existence of mind and body. A few remarks will place this doctrine in its proper light.

In the first place, we are not conscious of the existence of the organs by means of which the mind operates in this . life, and, in consequence, many acts appear to us to be purely mental, which experiment and observation prove in-contestibly to depend on corporeal organs. For example, in stretching out or withdrawing the arm, we are conscious of an act of the will, and of the consequent movement of the arm, but not of the existence of the apparatus by means of which our volition is carried into execution. Experi-

10 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

ment and observation, however, demonstate the existence of bones of the arm curiously articulated and adapted to motion ; of muscles endowed with the power of contraction ; and of three sets of nervous fibres all running in one sheath

-one communicating feeling, a second exciting motion, and a third believed to convey to the mind information of the state of the muscles, when in action ; all which organs, except the nerve of feeling, must combine and act harmoniously before the arm can be moved and regulated by the will. All that a person uninstructed in anatomy knows, is, that he wills the motion, and that it takes place ; the whole act appears to him to be purely mental, and only the arm. or thing moved, is conceived to be corporeal. Nevertheless, it is positively established by anatomical and physiological researches that this conclusion is erroneous-that the act is not purely mental, but is accomplished by the instrumentality of the various organs now enumerated. In like manner, every action of vision involves a certain state of the optic nerve, and every act of hearing a certain state of the tympanum ; yet of the existence and functions of these organs we obtain, by means of consciousness, no knowledge whatever.

Now, I go one step farther in the same path, and state, that every act of the will, every flight of imagination, every glow of affection, and every effort of the understanding, in this life, is performed by means of the cerebral organs, unknown to us through consciousness, but the existence of which may be demonstrated by experiment and observation ; in other words, that the brain is the organ of the mind

-the material condition without which no mental act is possible in the present world. The greatest physiologists admit this proposition without hesitation. The celebrated Dr Cullen of Edinburgh states, that " the part of our body more immediately connected with the mind, and therefore more especially concerned in every affection of the intellectual functions, is the common origin of the nerves ; which I shall, in what follows, speak of under the appellation of

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND,

the brain." Again, the same author says : " We cannot doubt that the operations of our intellect always depend upon certain motions taking place in the brain." The late Dr James Gregory, when speaking of memory, imagination, and judgment, observes, that " Although at first sight these faculties appear to be so purely mental as to have no connexion with the body, yet certain diseases which obstruct them prove, that a certain state of the brain is necessary to their proper exercise, and that the brain is the primary organ of their internal powers." The great physiologist of Germany, Blumenbach, says : " That the mind is closely connected with the brain, as the material condition of mental phenomena, is demonstrated by our consciousness, and by the mental disturbances which ensue upon affections of the brain." l According to Magendie, a celebrated French physiologist, " the brain is the material instrument of thought : this is proved by a multitude of experiments and facts."

" I readily concur," says Mr Abernethy, " in the proposition, that the brain of animals ought to be regarded as the organization by which the percipient principle becomes variously affected. First, because, in the senses of sight, hearing, &c. I see distinct organs for the production of each perception. Secondly, because the brain is larger and more complicated in proportion as the variety of the affections of the percipient principle is increased. Thirdly, because disease and injuries disturb and annul particular faculties and affections without impairing others. And, fourthly, because it seems more reasonable to me to suppose that whatever is perceptive may be variously affected by means of vital actions transmitted through a diversity of organization, than to suppose that such variety depends upon original differences in the nature of the percipient principle."

" If the mental processes," asks Mr Lawrence, " be not the functions of the brain, what is its office ? In animals which possess only a small part of the human cerebral struc-

1 Elliotson's translation of Blumenbach's Physiology, 4th edit. p. 196.

12 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

ture, sensation exists, and in many cases is more acute than in man. What employment shall we find for all that man possesses over and above this portion-for the large and prodigiously-developed human hemispheres I Are we to believe that these serve only to round the figure of the organ, or to fill the cranium?" l And in another place he says :- " In conformity with the views already explained respecting the mental part of our being, I refer the varieties of moral feeling, and of capacity for knowledge and reflection, to those diversities of cerebral organization which are indicated by, and correspond to, the differences in the shape of the skull." 2

Dr Mason Good, speaking of intellect, sensation,' and muscular motion, says :-" All these diversities of vital energy are now well known to be dependent on the organ of the brain, as the instrument of the intellectual powers, and the source of the sensific and motory ; though, from the close connexion and synchronous action of various other organs with the brain, and especially the thoracic and abdominal viscera, such diversities were often referred to several o* the latter in earlier ages, and before anatomy had traced them satisfactorily to the brain as their fountain-head. And of so high an antiquity is this erroneous hypothesis, that it has not only spread itself through every climate on the globe, but still keeps a hold on the colloquial language of every people ; and hence the heart, the liver, the spleen, the reins, and the bowels, generally are, among all nations, regarded, either literally or figuratively, as so many seats of mental faculties or moral feeling. . . . The study of anatomy, however, has corrected the loose and confused ideas of mankind upon this subject ; and while it distinctly shews us that many of the organs popularly referred to as the seat of sensation, do, and must, from the peculiarity of their nervous connexion with the brain, necessarily participate in the feelings and faculties thus generally ascribed to them, it also demonstrates that the primary source of these attri-

1 Lectures on Phyinoloyy, &c. Lect. 4. 2 Ibid. Sect. ii. ch. 8.

THE BRAIN THE. ORGAN OF THE MIND. 13

butes, the quarter in which they originate, or which chiefly influences them, is the brain itself." '

Dr Neil Arnott, in his Elements of Physics, writes thus : -" The laws of mind which man can discover by reason, are not laws of independent mind, but of mind in connection with body, and influenced by the bodily condition. It has been believed by many, that the nature of mind separate from body, is to be at once all-knowing and intelligent. But mind connected with body can only acquire knowledge slowly, through the bodily organs of sense, and more or less perfectly according as these organs and the central brain are perfect. A human being born blind and deaf, and therefore remaining dumb, as in the noted case of the boy Mitchell, grows up closely to resemble an automaton ; and an originally misshapen or deficient brain causes idiocy for life. Childhood, maturity, dotage, which have such differences of bodily powers, have corresponding differences of mental faculty : and as no two bodies, so no two minds, in their external manifestation, are quite alike. Fever, or a blow on the head, will change the most gifted individual into a maniac, causing the lips of virgin innocence to utter the most revolting obscenity, and those of pure religion to speak the most horrible blasphemy : and most cases of madness and eccentricity can now be traced to a peculiar state of the brain." (Introduction, p. xxiii.) Let it be observed, that most of these authors are not among the supporters of Phrenology.2

The fact that the mental phenomena of which we are conscious are the result of mind and brain acting together, is farther established by the effects of swooning, of compression of the brain, and of sleep. In profound sleep consciousness is entirely suspended : this fact is explicable on the principle of the organ of the mind being then in a state of

1 Good's Study of Medicine, 2d edit. iv. 3, 4.

2 Additional authorities are cited by Mr Wildsmith, in his excellent Inquiry concerning the Relative Connexion which subsists between the Mind and the Brain, London, 1828,

14 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

repose ; but it is altogether inconsistent with the idea of the immaterial principle, or the mind itself, being capable of acting independently of the brain-for if this were the case, thinking could never be interrupted by any material cause. In a swoon, blood is rapidly withdrawn from the brain, and consciousness is for the moment obliterated. So also, where part of the brain has been laid bare by any injury inflicted on the skull, it has been found that consciousness could be suspended at the pleasure of the surgeon, by merely pressing on the brain with his fingers, and that it could be restored by withdrawing the pressure. A few such cases may be cited :-

M. Richerand had a patient whose brain was exposed in consequence of disease of the skull. One day, in washing of the purulent matter, he chanced to press with more than usual force ; and instantly the patient, who, the moment before, had answered his questions with perfect correctness, stopped short in the middle of a sentence, and became altogether insensible. As the pressure gave her no pain, it was repeated thrice, and always with the same result. She uniformly recovered her faculties the moment the pressure was taken off. M. Richerand mentions also the case of an individual who was trepanned for a fracture of the skull, and whose faculties and consciousness became weak in proportion as the pus so accumulated under the dressings as to occasion pressure of the brain.1 A man at the battle of Waterloo had a small portion of his skull beaten in upon the brain and became quite unconscious and almost lifeless ; but Mr Cooper having raised up the depressed portion of bone, the patient immediately arose, dressed himself, became perfectly rational, and recovered rapidly.2 Professor Chapman of Philadelphia mentions in his Lectures, that he saw an individual with his skull perforated and the brain exposed, who used to submit himself to the same experiment of pressure as that performed on Richerand's patient, and who was

1 Nouveaux Elément de Physiologie, 7th edit., ii. 195-6.

2 Hennen's Principles of Military Surgery.

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND. 15

exhibited by the late Professor Wistar to his class. The man's intellect and moral faculties disappeared when pressure was applied to the brain : they were literally " held under the thumb," and could be restored at pleasure to their full activity.1 A still more remarkable case is that of a person named Jones, recorded by Sir Astley Cooper. This man was deprived of consciousness, by being wounded in the head, while on board a vessel in the Mediterranean. In this state of insensibility he remained for several months at Gibraltar, whence he was transmitted to Deptford, and subsequently to St Thomas's Hospital, London. Mr Cline, the surgeon, found a portion of the skull depressed, trepanned him, and removed the depressed part of the bone. Three hours after this operation he sat up in bed, sensation and volition returned, and in four days he was able to get up and converse. The last circumstance he remembered was the capture of a prize in the Mediterranean thirteen months before.-A young man at Hartford, in the United States of America, was rendered insensible by a fall, and had every appearance of being in a dying condition. Dr Brigham removed more than a gill of clotted blood from beneath the skull ; upon which " the man immediately spoke, soon recovered his mind entirely, and is now, six weeks after the accident, in good health both as to mind and body."2

The question may present itself, Why did these injuries, which were inflicted only on a small portion of the brain, induce general insensibility, instead of disturbing only a single faculty ? Answer.-The brain is soft and pulpy ; and is very full of bloodvessels, which during life contain a large quantity of blood. It is enveloped in air-tight membranes, so that it approaches very closely to the condition of a fluid mass contained within a hollow sphere. By the law which

1 Principles of Medicine, by Samuel Jackson, M.D.

2 Remarks on the Influence of Mental Cultivation, &c. upon Health. By Amariah Brigliam, M.D. 2d edit. p. 23. Boston, U. S. 1833. Several of the cases in the text have already been collected by this very intelligent writer.

16 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

regulates the pressure of fluids, force applied to any portion of such a mass, diffuses itself equally over the whole of it ; and every part is pressed with the same degree of force. This law applies to the brain ; und all the faculties are suspended, because all the brain is compressed. If a blow cut the skull and integuments, so as to allow the blood to flow outwardly, and the brain to protrude, general insensibility will not ensue.

PINEL relates a case which strikingly illustrates the connexion of the mind with the brain. " A man," says he, " engaged in a mechanical employment, and afterwards confined in the Bicêtre, experiences at regular intervals fits of madness characterized. by the following symptoms. At first there is a sensation of burning heat in the abdominal viscera, with intense thirst, and a strong constipation ; the heat gradually extends to the breast, neck, and face,-producing a flush of the complexion ; on reaching the temples, it becomes still greater, and is accompanied by very strong and frequent pulsations in the temporal arteries, which seem as if about to burst : finally, the nervous affection arrives at the brain ; the patient is then seized with an irresistible propensity to shed blood ; and if there be a sharp instrument within reach, he is apt to sacrifice to his fury the first person who presents himself."1 The same writer speaks of another insane patient, whose manners were remarkably mild and reserved during his lucid intervals, but whose character was totally altered by the periodical morbid excitement of his brain ; for, says Pinel, " on the return of the paroxysm, particularly when marked by a certain redness of the face, excessive heat in the head, and a violent thirst, his walk is precipitate, his look is full of audacity, and he experiences the most violent inclination to provoke those who approach him, and to fight with them furiously."2 Dr Richy has recorded the case of a Madagascar negro, who had an attack of an intensely ferocious delirium, in consequence

1 Pinel, surr l'Aliénation Mentale, p. 157, § 160.

2 Op. cit. p. 101. § 116.

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND. 17

of a wound on the head near the lower part of the left parietal bone. When recovering, he was calmer, and less blood-thirsty ; but an overpressure of his bandage on the wound brought back his furious paroxysms.1

That the brain is the organ of the mind, is strongly confirmed by the phenomena observed when it is exposed to view, in consequence of the removal of a part of the skull. Sir Astley Cooper mentions the case of a young gentleman who was brought to him after losing a portion of his skull just above the eyebrow. " On examining the head," says Sir Astley, " I distinctly saw the pulsation of the brain ; it was regular and slow ; but, at this time, he was agitated by some opposition to his wishes, and directly the blood was sent with increased force to the brain, and the pulsation became frequent and violent. If, therefore," continues Sir Astley, " you omit to keep the mind free from agitation, your other means will be unavailing" in the treatment of injuries of the brain.2

In a case of a similar description, which fell under the notice of Blumenbach, that physiologist observed the brain to sink whenever the patient was asleep, and to swell again with blood the moment he awoke.3

A third case is reported by Dr Pierquin, as having been observed by him in one of the hospitals of Montpelier, in the year 1821. The patient was a female, who had lost a large portion of her scalp, skull, and dura mater, so that a corresponding portion of the brain was subject to inspection. When she was in a dreamless sleep, her brain was motionless, and lay within the cranium. When her sleep was imperfect, and she was agitated by dreams, her brain moved, and protruded without the cranium, forming cerebral hernia. In vivid dreams, reported as such by herself, the protrusion was considerable ; and when she was perfectly awake, especially if engaged in active thought or sprightly

1 Journal de la Société Phrénologigue de Paris, No. 2. p. 171.

2 Sir A. Cooper's Lectures on Surgery, by Tyrrel, i. 279.

3 Elliotson's Blumenbach, 4th edit. p. 283.

B

18 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

conversation, it was still greater,1 A writer in the Medico-Chirurgical Review, after alluding to this case, mentions that many years ago he had " frequent opportunities of witnessing similar phenomena in a robust young man, who lost a considerable portion of his skull by an accident which had almost proved mortal. When excited by pain, fear, or anger, his brain protruded greatly, so as sometimes to disturb the dressings, which were necessarily applied loosely ; and it throbbed tumultuously, in accordance with the arterial pulsations."2

The cause of these appearances obviously was, that the brain, like the muscles and other organs of the body, is more copiously supplied with blood when in a state of activity than while at rest ; and that when the cerebral bloodvessels were filled, the volume of the brain was augmented, and the protrusion above noticed took place.

On 15th May 1839, I saw, in New York, a girl of eight years of age, who four years before that time had fallen from a height of two stories, and fractured her skull extensively at the crown. Dr Matt removed a large portion of the two parietal bones, and found the brain and pia mater uninjured. I saw the pieces of the skull which had been removed. They might be about three inches by three and a half in superficial extent. The external integuments were replaced, and re-united over the wound. On placing my hand on the head, I felt that the skull was absent over the organs of Self-Esteem and Love of Approbation.; also over a small part of Conscientiousness, and the posterior margin of Firmness. Her father, James Gmapes, Esq. mentioned that before the accident, he considered her rather dull. Her mother did not concur in this opinion, but both agreed that since her recovery, she had been acute, and fully equal to children of her own age in ability. Her brain is favourably developed. Her father said that when the brain was visible, he distinctly saw particular parts of

1 Annals of Phrenology, No. 1. Boston, U. S., Oct. 1833, p. 37. ' Medico-Chirurgical Review, No. 46. p. 366. Oct. 1835.

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND. 19

it move when the child was agitated by particular feelings.1 A very striking argument in favour of the doctrine that the brain is the organ of the mind, is found in the numerous cases in which changes of character have been produced by injuries inflicted on the head. In this way the action of the brain is sometimes so much altered, that high talents are subsequently displayed where mediocrity or even extreme dulness existed before ; in other instances, the temper from being mild and amiable becomes irritable and contentious ; while in others, again, it occasionally happens (in consequence of the injury depressing instead of exalting the tone of the brain), that talents formerly enjoyed are obscured or lost. Dr Gall refers to a case reported by Hildanus, of a boy ten years old, a portion of whose skull was accidentally driven in ; nothing was done to remedy the injury, and the boy, who had previously given promise of excellent parts, became altogether stupid, and in that condition died at the age of forty. He adds a similar case of a lad whose intellectual vivacity was destroyed by cerebral disease accompanied with fever.2 The aeronaut Blanchard had the misfortune to fall upon his head, and thenceforward his mental powers were evidently feeble ; after death Dr Gall found his brain diseased.3

Even in the Edinburgh Review, where the dependence of the mind upon the brain was formerly held to be exceedingly questionable,4 the doctrine is now admitted in all its latitude. " Almost from the first casual inspection of animal bodies," says a writer in No. 94, " the brain was regarded as an organ of primary dignity, and, more particularly in the human subject, the seat of thought and feeling, the centre of all sensation, the messenger of intellect, the presiding organ of the bodily frame." " AU this superiority (of man over the brutes), all these faculties which elevate and dig-

1 See a more particular report of this case in the present volume vane 366-7.

* Gall, ii. p. 172. s Id- p 1?3

4 See No. 48. Article 10 ; also No. 88, cited below.

20 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

nify him, this reasoning power, this moral sense, these capacities of happiness, these high aspiring hopes, are felt, and enjoyed, and manifested, by means of his superior nervous system. Its injury weakens, its imperfection limits, its destruction (humanly speaking) ends them. "

More recently one of the most esteemed medical journals, viz., The British and Foreign Medical Review, says, " We must reiterate our decided conviction that the proposition, that the brain is the organ of the mind, forms peculiarly a principle of phrenological science, and that, however general the assent yielded to the same in the present day, even by parties who would disdain to be considered phrenologists, it is not the less a principle strictly phrenological. Gall was the first who interrogated nature, in all her departments, to ascertain the fallacy or soundness of the principle in question ; and he was the first successfully to investigate certain facts that had seemed to militate against the proposition, and to show their entire accordance with the general rule. Hence we conceive, that whoever admits the function of the brain to be to develope the attributes of the conscious principle, is, pro tanto, a phrenologist, and a disciple of Gall. In fine, Phrenology, as a science, has, in our estimation, established, by the method of induction, the soundness of its first principle, that the brain is the organ of the mind.''''1

Besides referring to these facts and authorities, I may remark, that consciousness localizes the mind in the head, and gives us a full conviction that it is situated there ; but consciousness does not reveal what substance is in the interior of the skull. It does not tell whether the mind occupies an airy dome, a richly furnished mansion, one apartment, or many ; or in what state or condition it resides in its appointed place. It is only on opening the head that we discover that the skull incloses the brain ; and then, by

1 The objection that this doctrine leads to Materialism is considered in vol. ii., page 407.

Additional evidence that the brain is the organ of the mind will be found in the Appendix, No. I,

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND. 21

an act of the understanding, we infer that the mind must have been connected with it in its operations.

It is worthy of observation also, that the popular notions of the independence of the mind on the body are modern, and the offspring of philosophical theories that have sprung up chiefly since the days of Locke. In Shakspeare, and our older writers, the word " brain" is frequently used as implying the mental functions ; and, even in the present day, the language of the vulgar, which is less affected by philosophical theories than that of polite scholars, is more in accordance with nature. A stupid person is vulgarly called a numbskull, a thick-head ; or said to be addle-pated, badly furnished in the upper-story ; while a clever person is said to be strong-headed or long-headed, to have plenty of brains ; a madman is called wrong in the head, touched in the noddle, &c. When a catarrh chiefly affects the head, we complain of stupidity, because we have such a cold in the head.1

The principle which I have so much insisted on, that we are not conscious of the existence and functions of the organs by which the mind acts, explains the source of the metaphysical notion which has affected modern language, that we know the mind as an entity by itself. The acts which really result from the combined action of the mind and its organs, appear, previously to anatomical and pathological investigation, to be produced by the mind exclusively ; and hence have arisen the neglect and contempt with which the organs have been treated, and the ridicule cast upon those who have endeavoured to shew their importance in the philosophy of mind. After the explanations given above, the reader will appreciate the real value of the following statement by Lord Jeffrey, in his strictures on the second edition of this work, in the 88th number of the Edinburgh Review. His words are: "The truth, we do not scruple to say it, is, that there is not the smallest reason for supposing that the mind ever operates through the

1 Elliotson's Blumenbach, p. 66.

22 THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

agency of any material organs, except in its perception of material objects, or in the spontaneous movements of the body which it inhabits." And, " There is not the least reason to suppose that any of our faculties, but those which connect us with external objects, or direct the movements of our bodies, act by material organs at all :" that is to say, feeling, fancy, and reflection, are acts so purely mental, that they have no connection with organization.

Long before Lord Jeffrey penned these sentences, however, Dr Thomas Brown had written, even in the Edinburgh "Review, that " memory, imagination, and judgment, may be all set to sleep by a few grains of a very common and simple drug ;" and Dr Cullen, Blumenbach, Dr Gregory, Magendie, and in short all physiological authors of eminence, had published positive statements, that the mental faculties are connected with the brain.

Lord Brougham also, in his Discourse of Natural Theology, argues in favour of the mind's independence of matter in this life, and adduces in support of his position the phenomena of dreaming, and the allegation that " unless some unusual and violent accident interferes, such as a serious illness or a fatal contusion, the ordinary course of life presents the mind and the body running courses widely different, and in great part of the time in opposite directions." (P. 120.) But Mr Stewart has furnished a satisfactory answer to this remark. " In the case of old men," says he, " it is generally found that a decline of the faculties keeps pace with the decay of bodily health and vigour. The few exceptions that occur to the universality of this fact, only prove that there are some diseases fatal to life, which do not injure those parts of the body with which the intellectual operations are more immediately connected."1 Lord Brougham, moreover, is glaringly inconsistent with himself. He first maintains that the mind is wholly independent of the body, and then admits that " a serious illness" is capable of impairing its

1 Outlines of Moral Philosophy, p. 233.

THE BRAIN THE ORGAN OF THE MIND.

power. Yet how, on his hypothesis, can it be affectable by this any more than by the slightest disease ?

It is a popular opinion, that in pulmonary consumption, and other lingering diseases attended with waste of the body, the mind nevertheless continues to act with entire vigour up to the very day or hour of dissolution. This notion, if true, would militate against the doctrine of the mind being affected by the state of the organs ; but it is really unfounded. There is a difference between derangement of an organ and mere weakness in its functions. In pulmonary consumption the lungs alone are disorganized ;-the brain and other organs, remaining entire in their structure, are sound although weakened in their functions. The mind in such patients, therefore, does not become disordered ; but its vigour is unquestionably impaired. In the case of the patient's legs, the bones and muscles remaining entire, he can -walk : In health, however, he could have accomplished a journey of many miles without fatigue, whereas he cannot in disease do more than cross his bed-room. It might certainly be said that he could walk to the last, but it could not with truth be maintained that his power of perambulation was as great at his death as in health ; and so it is with the brain and the mind.

What, then, does the proposition that the brain is the organ of the mind imply ? Let us take the case of the eye as somewhat analogous. If the eye be the organ of vision, it will be conceded, first, That sight cannot be enjoyed without its instrumentality ; secondly, That every act of vision must be accompanied by a corresponding state of the organ, and, vice versa, that every change of condition in the organ must influence sight ; and, thirdly, That the perfection of vision will be in relation to the perfection of the organ. In like manner, if the brain be the organ of the mind, it will follow that the mind does not act in this life independently of its organ-and hence, that every emotion and judgment of which we are conscious, is the result of the mind and its organ acting together ; secondly, that every mental affection

24 PLURALITY OF FACULTIES AND ORGANS.

must be accompanied by a corresponding state of the organ, and, vice versa, every state of the organ must be attended by a certain condition of the mind ; and, thirdly, that the perfection of the manifestations of the mind will bear a relation to the perfection, of its organ. These propositions appear to be incontrovertible, and to follow as necessary consequences from the -simple fact that the mind acts by means of organs. But if they be well-founded, how important a study does that of the organs of the mind become ! It is the study of the" mind itself, in the only condition in which it is known to us ; and the very- fact that in past ages the mind has been studied without reference to organization, accounts for the melancholy truth, that, independently of Phrenology, no mental philosophy suited to practical purposes exists.

Holding it then as established by the evidence of the most esteemed physiologists, and also by observation, that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that the state of the brain influences that of the mental powers, the next question which presents itself is, Whether the mind in every act employs the whole brain as one organ, or whether separate mental faculties are connected with distinct portions of the brain as their respective organs? The following considerations may throw light on this question.

lst, In all ascertained instances, different functions are never performed by the same organ, but the reverse ; each function has an organ for itself: the stomach, for instance, digests food, the liver secretes bile, the heart propels the blood, the eyes see, the ears hear, the tongue tastes, and the nose smells. Nay, on analyzing these examples, it is found that wherever the function is compound, each element of it is performed by means of a distinct organ : thus, to accomplish the lingual duties, there is one nerve whose office is to move the tongue, another nerve whose duty it is to communicate the ordinary sense of feeling to the tongue, and a third nerve which conveys the sensation of taste. A similar combination of nerves takes place in the hands, arms, and

PLURALITY OF FACULTIES AND ORGANS. 25

other parts of the body which contain voluntary muscles : one nerve gives motion, another bestows feeling, while a third conveys to the mind a knowledge of the state of the muscle ; and, except in the case of the tongue, all these ' nerves are blended in one common sheath.

In the economy of the human frame, there is no ascertained example of one nerve performing two functions, such as feeling and communicating motion, or seeing and hearing, or tasting and smelling. The spinal marrow consists of three double columns : the anterior column of each lateral division is for motion, the posterior for sensation, and the middle for respiration.1 In the case of the brain, therefore, analogy would lead us to expect, that if reasoning be an act essentially different from loving or hating, there will be one organ for reasoning, another for loving, and a third for hating.

2dly? It is an undisputed truth, that the various mental powers of man appear in succession, and, as a general rule, that the reflecting or reasoning faculties are those which arrive latest at perfection. In the child, the emotions of fear and of love appear before that of veneration ; and the capacity of observing the existence and qualities of external objects arrives much sooner at maturity than that of abstract reasoning. Daily observation shews that the brain undergoes a corresponding change ; whereas we have no evidence that the immaterial principle varies in its powers from year to year. If every faculty of the mind be connected with the whole brain, this successive development of mental powers is utterly at variance with what we should expect a priori ; because, if the general organ is fitted for manifesting with success one mental faculty, it ought to be equally so for manifesting all. On the contrary, observation shews that dif-

1 The function of the middle column is disputed, but the connection of the others with sensation and motion is admitted by the best physiologists.

2 Most of the following arguments are taken from Dr Andrew Combe's Observations on Dr Barclay's Objections to Phrenology, published in the Transactions of the Phrenological Society (Edinburgh, 1824), page 413.

26 PLURALITY OF FACULTIES AND ORGANS.

ferent parts of the brain are really developed at different periods of life, corresponding with the successive evolution of the faculties. In infancy, according to Chaussier, the cerebellum forms one-fifteenth of the encephalic mass, and, in adult age, from one-sixth to one-eighth ; its size being thus in strict accordance with the energy of the sexual propensity, of which it is the organ. In childhood, the middle part of the forehead generally predominates ; in later life, the upper lateral parts become more prominent-which facts also are in strict accordance with the periods of unfolding of the observing and reasoning powers.

3dly, Genius is almost always partial, which it ought not to be if the organ of the mind were single. A genius for poetry, for mechanics, for drawing, for music, or for mathematics, sometimes appears at a very early age in individuals who.'in regard to all other pursuits, are mere ordinary men, and who, with every effort, can never attain to any thing above mediocrity.