George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

21.-IMITATION.

DR GALL gives the following account of the discovery of this faculty and organ. One day, a friend with whom he was conversing about the form of the head, assured him that his had something peculiar about it, and directed his hand to the superior anterior region of the skull. This part was elevated in the form of a segment of a sphere ; and behind the protuberance there was a transverse depression in the middle of his head. Before that time Dr Gall had not ob-

criminate between primitive faculties and their modes of action, runs through almost all his writings. Sometimes he recognises original principles distinctly, as in pp. 367, 371, 372. On other occasions, he loses sight of the distinction between them and modes of action, I shall revert to this subject when treating of Association.

512 IMITATION.

served such a conformation. This man had a particular talent for imitation. Dr Gall immediately repaired to the institution for the deaf and dumb, in order to examine the head of a pupil named Casteigner, who only six weeks before had been received into the establishment, and, from his entrance, had attracted notice by his amazing talent for mimicry. On the mardigras of the carnival, when a little play was performed at the institution, he had imitated so perfectly the gestures, gait, and looks of the director, inspector, physician, and surgeon, of the establishment, and above all of some women, that it was impossible to mistake them. This exhibition was the more amusing, as nothing of the kind was expected from the boy, his education having been totally neglected. Dr Gall states, that he found the part of the head in question as fully developed in this individual as in his friend Hannibal, just mentioned.

Is the talent for mimicry, then, said Dr Gall, founded on a particular faculty and organ ? He sought every opportunity of multiplying observations. He visited private families, schools, and public places, and everywhere examined the heads of individuals who possessed a distinguished talent for mimicry. At this time, Monsieur Marx, secretary to the minister of war, had acquired a great reputation, by playing several characters in a private theatre. Dr Gall found in him the same part of the head swelling out as in Casteigner and Hannibal. In all the other persons whom he examined, he found the part in question more or less elevated in proportion to the talent for imitation which they possessed. It is told of Garrick, says Dr Gall, that he possessed such an extraordinary talent for mimicry, that, at the court of Louis XV., having seen for a moment the King, the Duke d'Aumont, the Duke d'Orléans, Messrs d'Aumont, Brissac, and Richelieu, Prince Soubise, &c., he carried off the manner of each of them in his recollection. He invited to supper some friends who had accompanied him to court, and said, " I have seen the court only for an instant, but I shall shew you the correctness of my powers of ob-

IMITATION. 513

servation, and the extent of my memory :" and placing his friends in two files, he retired from the room, and on his immediately returning, his friends exclaimed, "Ah ! here is the king, Louis XV. to the life !" He imitated in succession all the other personages of the court, who were instantly recognised. He imitated not only their walk, gait} and figure, but also the expression of their countenances. Dr Gall, therefore, easily understood how greatly the faculty of Imitation would assist in the formation of a talent for acting ; and he examined the heads of the best performers at that time on the stage of Vienna. In all of them he found the organ large. He got the skull of Junger, a poet and comedian, and afterwards used it to demonstrate this organ. Subsequently, he and Dr Spurzheim, in their travels, met with many confirmations of it. In particular, in the house of correction at Munich, they saw a thief who had it large. Dr Gall said he must be an actor ; surprised at the observation, he acknowledged that he had for some time belonged to a strolling company of players. This circumstance was not known in the prison when Dr Gall made the observation. On these grounds, Dr Gall conceived himself justified in admitting the existence of a special talent for imitation ; that is to say, a faculty which enables the possessor in some degree to personify the ideas and sentiments of others, and to exhibit them exactly by gestures ; and he considered this talent to be connected with the particular organ now pointed out. I am acquainted with a lady in whom the organ is largely developed, and she has a strong tendency to imitate every sound she hears. If she be alone, or with a familiar friend, and she hear a cock crow, she will crow too. One day I sat beside her while she was reading. The growl of distant thunder reached her ear, and, to my amazement, I heard the very echo of its roar given forth by her throat. She did not think what the sound was which she imitated, until she saw me smile. She was then a little shocked at her own unintentional want of reverence in mimicking the thunder.

514 IMITATION.

This faculty appears to me to confer the tendency to represent by sounds, gestures, looks, and forms, the ideas and emotions generated by all the other faculties. It is a power essentially of expression ; and does not originate any special sentiment or emotion.

Dr Vimont remarks that this organ is large in persons addicted to affectation. " Nobody/' says he, " knows better than they how to reproduce the gestures which express a lively joy or poignant grief ; and if Secretiveness be well developed, they will not fail to assume those expressions and gestures which are best calculated to render themselves objects of interest to the spectators.5' This result follows only when Love of Approbation also predominates. I know great mimics who are not affected.

This organ contributes to render a poet or author dramatic ; such as Shakspeare, Corneille, Molière, Voltaire, &c. It is large in the portraits of Shakspeare, and also in the bust of Sir Walter Scott, whose productions abound in admirable dramatic scenes.

Mr Scott observes, that, in perfect acting, there is more than imitation,-there is expression of the propensities and sentiments of the mind in all the truth and warmth of natural excitement ; and this power of throwing real expression into the outward representation he conceives to depend upon Secretiveness.1 Thus, says Mr Scott, a person with much Imitation and little Secretiveness, could represent what he had seen, but he would give the externals only in his representation ; add Secretiveness, and he could then enter into any given character as it would appear if existing in actual nature : he could, by means of this latter faculty, call up all the internal feelings which would animate the original, and give not a copy merely, but another of the same, -a second edition, as it were, of the person represented. In this analysis of acting, perhaps too much influence is ascribed to Secretiveness, and too little to Imitation ; my

1 Trans. of the Phren. Soc, p. 169.

IMITATION. 515

own opinion, as expressed on p. 305, is, that Secretiveness produces chiefly a restraining effect, and that Imitation enables its possessor to enter into the spirit of those whom it represents.

As imitation, strictly considered, consists in reproducing pre-existing appearances, this faculty is greatly aided by a large endowment of Individuality and Eventuality. In the heads of Garrick, and of the late Mr Charles Mathews, the comedian, these organs were very largely developed in addition to Imitation. Mr Mathews, in his autobiography, speaks of " that irresistible impulse I had to echo, like a mocking-bird, every sound I heard.''

While, however, Secretiveness and Imitation together may thus be regarded as general powers, without which no talent for acting can be manifested, it is proper to observe, that the effect with which they can be applied in representing particular characters, will depend on the degree in which other faculties are possessed in combination with them. For example ; an actor very deficient in Tune, however highly he may be endowed with Secretiveness and Imitation, could not imitate Malibran, or, what is the same thing, perform her parts on the stage ; neither could an individual possessing little Self-Esteem and Destructiveness, represent with just effect the fiery Coriolanus ; because the original emotion of haughty indignation can no more be generated by Imitation and Secretiveness, without Destructiveness and Self-Esteem, than can melody without the aid of Tune. Hence, to constitute an accomplished actor, capable of sustaining a variety of parts, a generally full endowment of the mental organs is required. Nature rarely bestows all these in an eminent degree on one individual ; and, in consequence, each performer has a range of character in which he excels, and out of which his talents appear greatly diminished. I 'have found, in repeated observations, that the lines of success and failure bear reference to the organs fully or imperfectly developed in the brain. Actors incapable of

516 IMITATION.

sustaining the dignity of a great character, but who excel in low comedy, will be found deficient in Ideality ; while, on the other hand, those who tread the stage with a native dignity of aspect, and seem as if born to command, will be found to possess, with a generally large brain, Intellect largely developed ; and also Firmness, Self-Esteem, and Love of Approbation large. It does not follow, however, from these principles, that an actor, in his personal conduct, must necessarily resemble most closely those characters which he represents to the best advantage on the stage. To enable an individual to succeed eminently in acting Shylock, for example, Firmness, Acquisitiveness, and Destructiveness are indispensable ; but it is not necessary, merely because Shylock is represented as deficient in Benevolence, Conscientiousness, Veneration, and Love of Approbation, that the actor also should be so. The general powers of Imitation and Secretiveness, although they do not supply the place of faculties that are deficient, are quite competent to suppress the manifestations of incongruous sentiments. Hence, in his private character, the actor may manifest in the highest degree the moral sentiments ; and yet, by shading these for the time, by the aid of Secretiveness, and bringing into play only the natural language of the lower propensities, which also we suppose him to possess, he may represent the scoundrel to the life.

This faculty is indispensable to the portrait-painter, the engraver, and the sculptor ; and, on examining the heads of Mr W. Douglas, Mr Joseph, Mr Uwins, Sir W. Allan, Mr James Stewart, Mr Selby the ornithologist, and Mr Lawrence Macdonald, I found it large in them all. Indeed, in these arts, Imitation is as indispensable as Constructive-ness. It also aids the musician and linguist, and, in short, all who practise arts in which expression is an object. On this faculty, in particular, the power of the ventriloquist depends.1 In The Phrenological Journal, vol. xv. p. 80, the

1 See " Phrenological Explanation of the Vocal Illusions commonly

IMITATION. 517

organ is stated to have been very large in Mr Nightingale a very remarkable mimick, who, at the Adelphi Theatre of London, imitated the celebrated actors.

Dr Spurzheim, alluding to Imitation, Wonder, Ideality, Wit, and Tune, observes, that " it is remarkable that the anterior, lateral, and upper region of the brain contains the organs of such powers as seem to be given particularly for amusements and theatrical performances.''

Imitation gives the power of assuming those gestures which are expressive of the thoughts and feelings of the mind, and hence is requisite to the accomplished orator. In private life, some individuals accompany their speech with the most forcible and animated expressions of countenance ; -the nascent thought beams from the eye, and plays upon the features, before it is uttered in words ;-this is produced by much Imitation and Ideality.

In The Phrenological Journal., vol. xiv. pp. 138 and 342, will be found a very able essay on the " Functions of Imitation,5' by Mr Hudson Lowe. He is disposed to regard it as the organ of sympathy. In vol. xv. p. 358, the effect of Mesmerism in exciting the organ is described.

In children, Imitation is more active than in adults. Young persons are very apt to copy the behaviour of those with whom they associate ; and hence the necessity of setting a good example before them, even from the earliest years. " Children,'1 says Locke, " (nay men too) do most from example ; we are all a sort of chameleons, that still take a tincture from things near us."2 In several skulls of Russians in the collection of Dr Seiler, at Dresden, which I examined, this organ was considerably developed ; and this people is prone to imitation.

Cabanis relates a case in which the organ of Imitation seems to have been diseased. The patient felt himself uncalled Ventriloquism," by Mr Simpson, Pin-en. Journ., vol. i. p. 466 ; and additional illustrations, vol. ii. p. 582.

3 Locke's Thoughts concerning Education, § 67.

518 IMITATION.

pelled to repeat all the movements and attitudes which he witnessed. " If at any time they prevented him from obeying that impulse, either by constraining his limbs, or obliging him to assume contrary attitudes, he experienced insupportable anguish ; here, it is plain, the faculty of imitation was in a state of morbid excitement."1 " A young idiot girl," says Pinel, " whom I have long had under my care, has a most decided and irresistible propensity to imitate all that is done in her presence ; she repeats automatically every thing she hears said, and imitates the gestures and actions of others with the greatest accuracy."2 A case somewhat similar is recorded in The Philosophical Transactions, No. 129, and transferred into The Phrenological Journal, vol. x., p. 370.

This organ is possessed by some of the lower animals, such as parrots and monkeys, which imitate the actions of man. The faculty is very powerful in the Turdus Polyglottus, or mocking-bird. " Its own natural note," says Dr Good, " is delightfully musical and solemn ; but, beyond this, it possesses an instinctive talent of imitating the note of every other kind of singing-bird, and even the voice of every bird of prey, so exactly as to deceive the very kinds it attempts to mock. It is, moreover, playful enough to find amusement in the deception, and takes a pleasure in decoying smaller birds near it by mimicking their notes, when it frightens them almost to death, or drives them away with all speed, by pouring upon them the screams of such other birds of prey as they most dread.'13

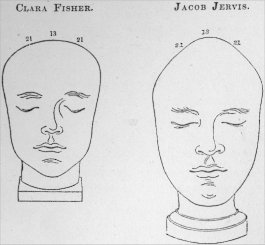

When this organ and that of Benevolence are both large, the anterior portion of the coronal region of the head rises high above the eyes, is broad, and presents a level surface, as in Miss Clara Fisher, who, at eight years of age, exhibited great talents as an actress. "When Benevolence is

1 Cabanis, Rapports du Physique et du Moral de l'Homme, tome i. p. 195.

" De l'Aliénation Mentait, 2d edit. p. 99, § 115.

s Good's Study of Medicine, 2d edit. vol. i. p. 463.

IMITATION. 519

large, and Imitation small, there is an elevation in the middle, with a rapid slope on each side, as in Jacob Jervis.

In both of these figures the head rises to a considerable height above the organs of Causality ; but in Jervis it slopes rapidly on the two sides of 13, Benevolence, indicating Imitation deficient ; whereas in Miss Clara Fisher it is as high at 21, Imitation, as at -Benevolence, indicating both organs to be large.

I beg leave to refer the reader to what is said on pp. 141-2, in regard to the method of estimating correctly the size of the organs which lie in the coronal region of the brain. I have known many mistakes committed in judging of the size of Imitation, in consequence of not attending to the rules there laid down. The organs of Causality lie at the points of ossification of the frontal bone, and in almost every head they may be distinctly recognised.

END OF VOLUME I.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.