George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

( 382 )

In vol. i. p. 160, I stated that, " in comparing the brains of the lower animals with the human brain, the Phrenologist looks solely for the reflected light of analogy to guide him in his researches, and never founds a direct argument in favour of the functions of the different parts of the human brain upon any facts observed in regard to the lower animals/'' I proceed to observe that, in comparing the bones, muscles, and bloodvessels of man with those of animals, we find a general analogy prevailing, and the nearer an animal approaches to the human race, in physical and mental condition and power, the more complete is the analogy between the structure and functions of particular organs in each, and the more numerous also are the organs in which this resemblance presents itself ; nor is any exception to this rule perceived in the nervous system. At certain points, however, the analogies fail, and good grounds may be assigned for this fact. Many persons reason on analogies between man and the lower animals, as if they imagined a man and a monkey to stand in the same relation to each other, as a large horse does to a diminutive pony ; they seem to expect that all the organs, or at least all the parts of the brain, should be moulded in the same form, and occupy the same relative positions, and differ only in size. But this is erroneous. A monkey is not a man made down into an inferior animal ; it is a creature of a distinct species. In so far as it possesses functions of mind and body similar to those of the human race, we may reasonably expect it to present organs of similar characters ; I say similar, and not perfect counter parts in the strictest sense of the word ; because the animal being a distinct creature, its organs will be modified to suit its particular condition. The non-professional reader will be enabled to appreciate the force of this remark by a single illustration. The function of a clock is to measure

COMPARATIVE PHRENOLOGY. 383

time, and that of a watch is the same : Is there any close analogy between their structures ? If the two machines were presented to a person ignorant of mechanics, and unacquainted with the uses of the clock and watch, it is probable that he might examine them in a general way, and declare that there was but a slight resemblance between them : But if we were to submit them to the examination of a philosophical watchmaker, he would declare that the analogies were numerous and striking ; he could point out wheels and pinions in each in which the resemblance was complete ; and he could add, that even between the weights and pendulum of the clock, and the mainspring and balance-wheel of the watch, a striking analogy is discernible by reflecting intellect, although to the eye their forms and appearances were widely different. He would draw these conclusions in consequence of his knowing accurately the structure and use of every part in each machine. It may well be conceived, that an observer, ignorant of all these particulars, might be blind to the analogies, not because they did not exist, but because, owing to his want of knowledge, he was not in a condition to perceive them. The watchmaker could without hesitation declare that the two machines acted on similar principles, and accomplish similar ends by similar means ; and that the differences between them bear an obvious relation to the different situations in which they are intended to act-the one stationary and perpendicular, the other subject to locomotion and to all varieties of position.

Keeping in view, then, that the inferior animals are not human beings made down by the mere omission of some organs, and the diminution of others, but distinct and independent creatures, whose parts, in so far as they resemble those of man, are modified to suit their own condition, and in whom special organs (wings and fins, for instance) exist, of which man is destitute,-I observe that the Phrenologist studies, in each class of animals, the structure of the brain and the manifestations of the mind. He selects, as subjects of observation, animals whose actions and brains he has the

384 COMPARATIVE PHRENOLOGY.

best opportunities of scrutinizing-individuals, also, in mature life and in full health. He compares in each the power of manifesting particular faculties with the size of particular portions of the brain ; and it is only when he has found, that in all cases (disease being absent) a large development of a particular part is accompanied with great power of manifesting a particular faculty, and vice versa, that he draws the inference that the part observed is the organ of that special power.

In applying this principle in the case of the lower animals, the process of observation must be the same as in man. It will not suffice to take up the brain of a sheep, a tiger, a fish, and a snake, and de piano compare them with the human brain, and jump to the conclusion, that there are, or are not, relations between their powers of manifesting the human faculties, and the size of corresponding parts of their brains. Before analogies in regard to particular qualities can be decided on, the student must know both of the things which he compares for then only can he be in a condition to judge whether analogies do or do not exist. The author of the article " Phrenology," in the " Penny Cyclopaedia," in urging objections against our views, overlooks this principle : He says,-" Yet this is so far from being the case, that phrenologists are compelled to rest their opinions almost exclusively on evidence derived from the comparison of the brains of different individuals of the same species, and to suppose that, though many faculties are the same in man and the lower animals, yet in each species they are manifested in some peculiar form and structure NOT ADMITTING OF COMPARISON with those of man" The " supposition" here ascribed to phrenologists is not entertained by them : they do not maintain that " the form and structure" of the brains of animals " do not admit of comparison with those of man." They have not affirmed that every brain possesses the same number of parts or organs, nor that all brains are alike perfect in their organization ; assumptions which the objection of the Cyclopsedist (without a shadow of reason) 2

COMPARATIVE PHRENOLOGY. 385

implies that they have made, or at least are bound to make. What they do affirm is-that the organic formation, be it ever so simple, which supplies the powers of perception, comparison, feeling, willing, and moving, is a brain, whether it be situated in the animal's head, back, belly, or tail, and whether it be round or square. But before the analogies in structure and functions between it and the human brain can be logically predicated, we must know the structure and functions of both. The correct statement, therefore, of their doctrine is,-that they insist on the necessity of understanding both of the things compared as an indispensable requisite to drawing sound inferences as to the existence or non-existence of analogies between them ; of studying each organ in each class of animals by itself, and then comparing them in order to decide on their analogies. They object to comparing the known with the unknown, which is what the Cyclopsedist insists on doing. Dr Vimont, under the head of " Cranioscopy of animals," says, " We should never commence the application of the principles of Phrenology on the crania of individuals belonging to different classes and orders of animals. They should always be on the crania of animals of the same species, and especially on animals the produce of the same parents. Every one who will take the trouble to repeat my experiments, by rearing before his own eyes, and during a long period, a large number of animals, and noting with care their most prominent faculties, will be qualified to make valuable cranioscopical observations on the chief vertebrated animals." After studying the faculties manifested by individuals of each class, and ascertaining the precise locality, appearance, and size, of the organ by means of which each faculty is manifested, and doing the same in man, the observer will be in a condition to judge of the analogies between them ; but not before.

Dr Vimont has followed

this course, and found numerous and striking analogies. The faculties, for

instance, of Ama-

vol. II. B b

386 COMPARATIVE PHRENOLOGY.

tiveness, Philoprogenitiveness, Combativeness, Destructiveness, Cautiousness, and others, not only are susceptible of comparison in man and the lower animals, but have been successfully observed in both ; then they have been compared ; and the analogies equally in the faculties and organs have been pointed out. Dr Kennedy, of Ashby-de-la-Zouch, communicated to me the following fact, of which he was a witness, and which may serve as one illustration of Dr Spurzheim's mode of studying the brains and faculties of the lower animals. " I spent a few days at Mr Strutt's of Belper, in Derbyshire, when Dr and Mrs Spurzheim were there on a visit. We used to walk a good deal over the lawn and shrubbery, where we had frequent opportunities of making observations on Mrs Strutt's pet family of tame pigeons, which, was numerous, and contained many varieties both British and foreign. Among them was a very beautiful one, to which our attention was always drawn by the extraordinary and elegant manifestation of an exorbitant Self-Esteem, the natural language of this organ being most prominently apparent. So much had this bird become an object of interest, that the conversation was often interrupted by the exclamation, ' Here comes Self-Esteem !' Well, by some accident poor Self-Esteem received an injury which ended in his death, and thus afforded us the advantage of a necrotomical inspection. Dr Spurzheim made a careful dissection of the brain, and clearly exhibited the organ which he had previously ascertained to be that of Self-Esteem, in a state of enormous preponderance in size relatively to the other cerebral parts. The Doctor proposed making a preparation of this brain in alcohol, and, if my recollections be correct, Mrs Spurzheim made a drawing of it." The Cyclopaedist's objection is, that phrenologists do not maintain that, after studying man, they are prepared to demonstrate direct analogies running through the orders, genera, and species of all the inferior animals, without studying each of them by

COMPARATIVE PHRENOLOGY. 387

itself. He objects that we do not regard a horse, an ass, a haddock, a frog, and a flea, as merely men made down ; that is to say, as manifesting precisely human faculties, by human organs, only omitting those which are unnecessary to their condition ! In no other sense have his words any rational meaning.

The real phrenological question is, Whether, in each species of animals, the size of each organ bears to that of the rest a proportion corresponding to the energy of each faculty in relation to the rest. No philosophical phrenologist compares the absolute size of the organs in one species with their absolute size in another, because to do so would be to transgress a very obvious rule of philosophy. The same cause, in the same circumstances', produces the same effects. When we apply this rule to Phrenology, we say that the same extent of size in an organ, in the same circumstances-L e. in individuals of the same species, age, health, and constitution, -will produce the same degree of energy of function. But the Cyclopsedist (correcting our philosophy) seems to expect that the same extent of size in the cerebellum, in different circumstances,-i, e. in individuals of every order, genus, and species, from man down to reptiles,-should produce the same energy of manifestations. Unless we hold this to be a philosophical principle, the comparison of the absolute size of the cerebellum (the mere size without regard to other circumstances) in the different species of animals is a mere waste of labour, which can lead to no result. Such a principle of comparison is condemned by the rules acknowledged by all cultivators of inductive science. That the phrenologists prosecute their researches by direct observations on individuals in each species is matter of public record. Dr Vimont's work on Comparative Phrenology is regarded as the highest authority ; and so far from founding his views on mere analogies, he has been led, for instance, by direct observations, to the opinion, that " the faculty of Destructiveness has been bestowed on vertebrated animals as well as on man, as a species of auxiliary to aid their other faculties.

388 CEREBRAL PHRENOLOGY.

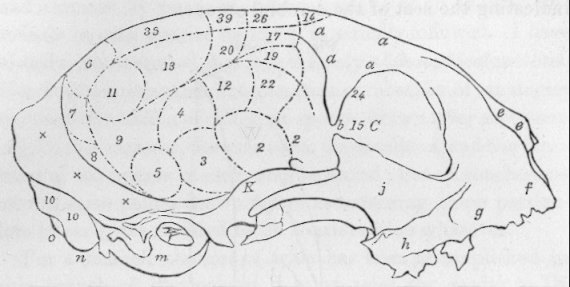

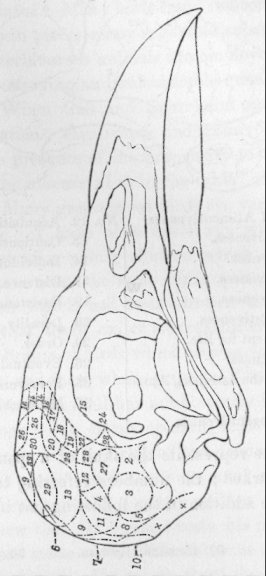

The beaver and the squirrel cut and tear in pieces the bark, leaves, and branches of trees, to construct a cabin or a nest. The marmot gnaws a great quantity of herbs to make a warm bed in winter. Many birds could not construct a nest unless they tore in pieces many vegetable substances. The whole lives of herbivorous animals are employed in cutting, dividing, and destroying an immeasurable quantity of vegetable matter. When Gall and Spurzheim cite, in support of their observations, carnivorous and granivorous birds, as examples of the presence of the propensity to destroy in the one case, and the absence of it in the other, they commit a double error. Many granivorous birds are very fond of animal substances. I have seen fowls run with avidity to flesh, even that of a young chicken which had been cut in pieces. I have seen the same birds quit grain in order to eat shell-fish which had been thrown to them. It is quite certain that there exists a great difference between the skulls and brains of birds which live exclusively on animal substances, and those whose principal food is vegetables, a difference which Dr Gall has not correctly indicated, as I shall demonstrate ; but, in my opinion, it is to be ascribed to the difference in the activity of the tendency to destroy in the different species, and not to its total absence in one of them." These remarks, be they well or ill founded in themselves, shew that Dr Vimont rests his opinions on direct observations made on the different races of animals, and not on loose analogies. He has observed the energy of particular mental powers in individuals of each species, and compared this power with the size of particular parts of the brain in each, and by this means assigned special localities to different faculties, and special functions to different parts of the brain, in the different races. The positions of the organs, as well as the size of each in relation to the others, he finds to be modified in each species. He gives, for example, in Figure 1., the skull of a full-grown cat, and delineates the organs on it as follows :

CEREBRAL

PHRENOLOGY. 389

Fig. 1. full-grown cat.

No. 2. Organ of Alimentiveness.

3. Destructiveness.

4. Secretiveness.

5. Combativeness.

6. Inhabitiveness.

7. Concentrativeness.

8. Attachment for life.

9. Adhesiveness.

10. 10. And the asterisks, Amativeness.

No. 12. Acquisitiveness.

13. Cautiousness.

14. Individuality. 17. Distance.

19. ^Resistance (Weight).

20. Locality.

22. Order.

26. Eventuality.

35. Perseverance (Firmness).

39. Mildness.

1 The scale of this figure is reduced one-half.

390 CEREBRAL PHRENOLOGY.

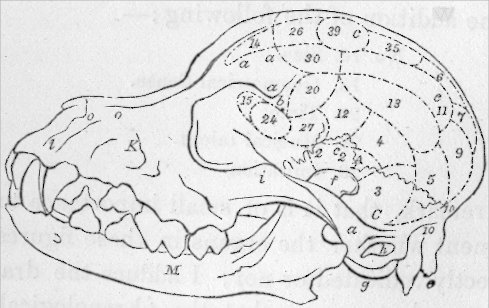

In fig. 3. he represents the skull of a crow with numbers indicating the seat of the cerebral organs. Fig. 3. crow.

The numbers refer to the same organs as in figures 1. and 2., with the addition of the following :-

No. 16. Size.

18. Geometrical Sense.

23. Time.

28. Musical talent.

29. Imitation.

I again remark, that it is of small importance to my present argument whether the organs in these figures have all been correctly indicated or not ; I adduce the drawings on this occasion only to prove that the phrenological mode of

CEREBRAL PHRENOLOGY. 391

studying the functions of different parts of the brain in man and animals, by means of observations made on known individuals in each species by itself, is actually followed. I have already demonstrated that it is the only philosophical method. Conclusions regarding the presence or absence of analogies between the brains of different species drawn after ascertaining, in this manner, the existence, the localities, and the functions of the organs in each, may be sound ; but all conclusions on the same points drawn before ascertaining these particulars in each, are entitled to no consideration whatever.

For a detailed account of what has been accomplished in this branch of Phrenology, I must refer the reader to Dr Vimont's valuable work, already so frequently referred to, " Traité de Phrenologie" and to the Phrenological Journal, vol. xiv. pp. 169 and 262, in which I have endeavoured to answer the objections against Phrenology founded on comparative anatomy.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.