George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

5.-COMBATIVENESS.

THIS organ is situated at the posterior-inferior angle of the parietal bone, a little behind and up from the ear.

Dr Gall gives the following account of its discovery. After he had abandoned all the metaphysical systems of mental philosophy, and become anxious to discover, by means of observation, the primitive propensities of human nature, he collected in his house a number of individuals of the lower classes of society, following different occupations, such as coach-drivers, servants, and porters. After acquiring their confidence, and disposing them to sincerity, by giving them

244 COMBATIVENESS.

wine and money, he drew them into conversation about each other's qualities, good and bad, and particularly about the striking characteristics in the disposition of each. In the descriptions which they gave of each other, they adverted much to those individuals who everywhere provoked quarrels and disputes ; they also distinguished those of a pacific disposition, and spoke of them with contempt, calling them poltroons. Dr Gall became curious to discover, whether the heads of the bravoes whom they described differed in any respect from those of the pacific individuals. He ranged them on opposite sides, and found, that those who delighted in quarrels had that part of the head immediately behind and a little above the ear much larger than the others.

He observes, that there could be here no question about the influence of education, and that this prominent feature in the character of each could never be attributed to the influence of external circumstances. Men in the rank to which they belonged, abandon themselves without reserve to the impulses of their natural dispositions.

The spectacle of fighting animals was, at that time, still existing at Vienna. An individual belonging to the establishment was so extremely intrepid, that he frequently presented himself in the arena quite alone, to sustain the combat against a wild boar or a bull. In his head, the organ was found to be very large. Dr Gall next examined the heads of several of his fellow-students, who had been banished from universities for exciting contentions and continually engaging in duels. In them, also, the organ was large. In the course of his researches, he met with a young lady who had repeatedly disguised herself in male attire, and maintained battles with the other sex ; and in her head, also, the organ was large. On the other hand, he examined the heads of individuals who were equally remarkable for want of courage, and in them the organ was small. The heads of the courageous persons varied in every other point, but resembled each other in being broad in this place,

COMBATIVENESS. 24-5

Equal differences were found in the other parts of the heads of the timid, when compared with each other, but all were deficient in the region of Combativeness.

This faculty has fallen under the lash of ridicule, and it has been objected that the Creator cannot have implanted in the mind a faculty for fighting. The objectors, however, have been as deficient in learning as in observation of human nature. The profoundest metaphysicians admit its existence, and the most esteemed authors describe its influence and operations. The character of Uncle Toby, as drawn by Sterne, is in general true to nature ; and it is a personification of the combative propensity, combined with great benevolence and integrity. " If," says Uncle Toby, " when I was a school-boy, I could not hear a drum beat but my heart beat with it, was it my fault ? Did I plant the propensity there ? Did I sound the alarm within, or Nature" He proceeds to justify himself against the charge of cruelty supposed to be implied in a passion for the battle-field. " Did any one of you," he continues, " shed more tears for Hector ? And when King Priam came to the camp to beg his body, and returned weeping back to Troy without it,-you know, brother, I could not eat my dinner. Did that bespeak me cruel ? Or, because, brother Shandy, my blood flew out into the camp, and my heart panted for war, was it a proof that it-could not ache for the distress of war too ?"

Tacitus, in his history of the war by Vespasian against Vitellius, mentions, that " Even women chose to enter the capitol and abide the siege. Amongst these, the most signal of all was Verulana Gracilia, a lady, who followed neither children nor kindred, nor relations, but followed only the war."-Lib. iii. " Courage," says Dr Johnson, " is a quality so necessary for maintaining virtue, that it is always respected, even when it is associated with vice."

Mr Stewart and Dr Reid admit this propensity under the name of "sudden resentment ;" and Dr Thomas Brown, under the name of " instant anger," gives an accurate and beautiful description of it when acting in combination with Destruc-

246 COMBATIVENESS.

tiveness. " There is a principle in our mind" says he, " which is to us like a constant protector ; which may slumber, indeed, but which slumbers only at seasons when its vigilance would be useless, which awakes therefore at the first appearance of unjust intention, and which becomes more watchful and more vigorous in proportion to the violence of the attack which it has to dread. What should we think of the providence of nature, if, when aggression was threatened against the weak and unarmed, at a distance from the aid of others, there were instantly and uniformly, by the intervention of some wonder-working power, to rush into the hand of the defenceless, a sword or other weapon of defence ? And yet this would be but a feeble assistance, if compared with that which we receive from those simple emotions which Heaven has caused to rush, as it were, into our mind, for repelling every attack."-Vol. iii. 324. This emotion is exactly the phrenological propensity of Combativeness aided by Destructiveness. The chief difference between Dr Brown's views and ours is, that he regards it as a mere susceptibility of emotion, liable to be called into action when provocation presents itself, but slumbering in quiescence in ordinary circumstances ; while we look upon it as also a spontaneously active impulse, exerting an influence on the mental constitution, independently of unjust attack. It is to express this active quality, that the term Combativeness is used to designate the faculty.

Combativeness, then, confers the instinctive tendency to oppose. In its lowest degree of activity it leads to simple resistance ; in a higher degree to active aggression, either physical or moral, for the purpose of removing obstacles. Courage is the feeling which accompanies the active state of this propensity. Hence an individual with predominating Combativeness anticipates in a battle the pleasure of gratifying his ruling passion, and is blind to all other considerations. His love of contention is an instinct. He is a fighting animal. Courage, however, when properly directed, is useful to maintain the right. On this account, a consider-

COMBATIVENESS. 247

able endowment of it is indispensable to all great and magnanimous characters. Even in schemes of charity, or in plans for the promotion of religion or learning, opposition will arise, and Combativeness inspires its possessor with that instinctive boldness which enables him to look undaunted on a contest in virtue's cause, and to meet it without shrinking. Were the organ very deficient in the promoters of such schemes, they would be liable to be overwhelmed by contending foes, and baffled in all their exertions. Indeed, I have observed that the most actively benevolent individuals of both sexes-those who, in person, minister to the relief of the poor, and face poverty and vice in their deepest haunts, to relieve and correct them-have this organ fully developed.

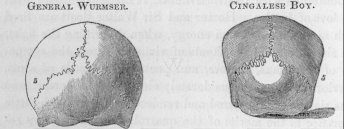

The organ is large in valiant warriors. In the skulls of King Robert Brace,1 and General Wurmser, who defended Mantua against Bonaparte, and whom the latter described as a fighting dragoon, it is exceedingly conspicuous. The subjoined figures represent Wurmser's skull contrasted at this organ with the skull of a Cingalese boy, in which it is small. The figures of Hare and Melancthon, on p. 141,

exhibit Combativeness largely and moderately developed. and the reader will find additional examples of its great development in the heads of Caracalla and the Roman Gladiator, delineated in Dr Spurzheim's Physiognomy, plates 14 and 32. It is very large in Linn, and moderate in the Rev. Mr M., whose heads are represented on p. 184 of the present volume.

1 Trans Phren. Soc., p. 247.

248 COMBATIVENESS.

In feudal times great Combativeness was more essential to a leader than it is in modern warfare. Richard Cour de Lion, Brace, and Wallace, could command the fierce barbarians whom they led to the field, only by superior personal prowess ; and, indeed, hope of victory was then founded, to a great extent, on the dexterity with which the chief could wield his sword. In modern warfare comprehensiveness of intellect is more requisite in a general ; but still Combativeness is a valuable element in his constitution. Napoleon distinguished accurately between these two qualities. He describes Ney and Murat as men in whom animal courage predominated over judgment ; and notices their excellence in leading an attack or a charge of cavalry, accompanied by incapacity for conducting great affairs. The most perfect military commander, he says, is formed when courage and judgment are in equilibria-in phrenological language, when the organs of Combativeness, moral sentiment, and reflection, are in just proportion to each other.

This faculty is of great service to a barrister : it furnishes him with the spirit of contention, and causes his energies to rise in proportion as he is opposed.

Combined with Destructiveness, it inspires authors with the love of battles. Homer and Sir Walter Scott are fired with more than common energy, when describing the fight, the slaughter, and the shouts of victory. From the sympathy of historians, orators, and poets, with deeds of arms, warriors are too inconsiderately elevated into heroes, and thus slaughter is fostered and rendered glorious, with little reference to the merits of the quarrel. Phrenology, by revealing the true source of the passion for war, will, it is to be hoped, one day direct the public sentiment to mark with its highest disapprobation every manifestation of this faculty that is not sanctioned by justice, and then we shall have fewer battles and inflictions of misery on mankind.

When too energetic and ill-directed, it produces the worst results. It then inspires with the love of contention for its own sake. In private society it produces the controver-

COMBATIVENESS. 249

sial opponent, who will wrangle and contest every point, and, "even though vanquished, who will argue still." When thus energetic and active, and not directed by the Moral Sentiments, it becomes a great disturber of the peace of the domestic circle : Contradiction is then a gratification, and the hours which should be dedicated to pure and peaceful enjoyment are embittered by strife. On the great field of the world, its abuses-lead to quarrels, and, when combined with Destructiveness, to bloodshed and devastation. In all ages, countless thousands have thronged round the standard raised for war, with an ardour and alacrity which shewed that they experienced pleasure in the occupation.

" Dr Parr was the admirer and advocate of pugilistic encounters among the boys who were his pupils ; and he defended the practice by the usual arguments, such as the exercise of a manly and useful art, calculated to inspire firmness and fortitude, and to furnish the means of defence against violence and insult. It was amusing to hear him speak of the tacit agreement which subsisted, he said, between himself and his pupils at Stanmore, that all their battles should be fought on a certain spot, of which he commanded a full view from his private room ; as thus he could see without being seen, and enjoy the sport without endangering the loss of his dignity. It is mentioned that his hind head was remarkably capacious."

Persons in whom the propensity is strong, and not directed by superior sentiments, are animated by an instinctive tendency to oppose every measure, sentiment, and doctrine, advocated by others ; and they frequently impose upon themselves so far, as to mistake this disposition for an acute spirit of philosophising, prompting them to greater rigour of investigation than other men. Bayle, the author of the Historical Dictionary, appears to have been a person of this description ; for, in writing, his general rule was to take the

1 Field's Memoir of Dr Parr, vol. i. p. 102. Phren. Journ., vol. xii. p. 159.

250 COMBATIVENESS.

side in opposition to every one else ; and hence it has been remarked, that the way to make him write usefully, was to attack him only when he was in the right, for he would then combat in favour of truth with all the energy of a powerful mind. William Cobbett mentions, that, in his youth, the rattle of the drum inviting him to war was enchanting music to his ears, and that he ardently became a soldier. In his maturer years, the combative propensity seemed to glow with equal activity in his mind, although exerted in a different direction. By speech and writing he contended in favour of every opinion that was interesting for the day. To Combativeness was owing no small portion of that boldness which even his enemies could not deny him to possess.

The organ is large also in persons who have murdered from the impulse of the moment, rather than from cool deliberate design. The casts of Haggart and Mary Machines are examples in point. The same is the case in several casts of Caribs' skulls, a tribe remarkable for the fierceness of their courage. The ancient artists have represented it large in their statues of gladiators. The practice of gladiatorship, as also the prize-fights of England, have for their object the gratification of this propensity.

When the organ is very large and active, it gives a hard thumping sound to the voice, as if every word contained a blow. Madame de Staël informs us, that Bonaparte's voice assumed this kind of intonation when he was angry ; and I have observed similar manifestations in individuals whom I knew to possess this part of the brain largely developed. When predominant, it gives a sharp expression to the lips, and the individual has the tendency to throw his head backwards, and a little to the side, in the direction of the organ, or to assume the attitude of a boxer or fencer.

When the organ is small, the individual experiences great difficulty in resisting attacks ; and he is not able to make his way in paths where he must invade the prejudices or encounter the hostility of others. Excessively timid children are generally deficient in this organ and possess a large

COMBATIVENESS. 251

Cautiousness ; their heads resembling the figure of the Cingalese boy on p. 247. I conceive the extreme diffidence and embarrassment of Cowper the poet to have arisen from such a combination ; and in his verses he loathes war with a deep abhorrence. Deficiency of Combativeness, however, does not produce fear ; for this is a positive emotion, often of great vivacity, which cannot originate from a mere negation of an opposite quality.

Combativeness is generally more developed in men than in women ; but, in the latter, it is sometimes large. If it predominates, it gives a bold and forward air to the female ; and when a child she would probably be distinguished as a romp.

In society it is useful to know the effects of this faculty, for then we can treat it according to its nature. When we wish to convince a person in whom the organ is large and Conscientiousness deficient, he will never endeavour to seize the meaning or spirit of our observations, but will pertinaciously put these aside, catch at any inaccuracy of expression, fly to a plausible although obviously false inference, or thrust in some extraneous circumstance, as if it were of essential importance, merely to embarrass the discussion. Individuals so constituted are rarely convinced of any thing ; and the proper course of proceeding with them, is to state our propositions clearly, and then drop the argument. This, by withdrawing the opportunity for exercising their Combativeness, is really a punishment to them ; and our views will have a better chance of sinking into their minds, unheeded by themselves, than if pertinaciously urged by us, and resisted by them, which last would infallibly be the case if we shewed anxiety for their conversion. A good test for a combative spirit is to state some clear and almost self-evident proposition as part of our discourse. The truly contentious opponent will instinctively dispute or deny it ; and we need proceed no farther.

When the organ is large, and excited by strong potations, an excessive tendency to quarrel and fight is the conse-

252 COMBATIVENESS.

quence. Hence some individuals, in whom it is great, but who, when sober, are capable of restraining it, appear, when inebriated, to be of a different nature, and extremely combative.1 The organ is liable also to excessive excitation through disease. Pinel gives several examples of monomania clearly referrible to it and Destructiveness. " A maniac,'' says he, " naturally peaceful and gentle in disposition, appeared inspired by the demon of malice during the fit. He was then in an unceasingly mischievous activity. He locked up his companions in their cells, provoked and struck them, and at every word raised some new quarrel and fighting." Another individual, who, during his lucid intervals, was mild, obliging, reserved, and even timid in his manners, became, during the fit, highly audacious, " and experienced the most violent propensity to provoke those who approached him, and to irritate and fight them avec outrance." On visiting London Bedlam in 1824,1 examined the head of a male patient, and pronounced Combativeness and Destructiveness to be uncommonly large. I was desired to look at his hands. They were fastened to rings in an iron girdle round his waist. He had committed murder in an access of fury, and was liable to relapses, in which he manifested these propensities with inordinate vehemence.

On the 16th day of July 1836, I was present at the post mortem examination of the brain of an old gentleman, who had long been remarkable for the mildness of his dispositions and the courtesy of his manners, until suddenly, in August 1832, he became extremely irritable and violent in temper. The son of his gardener describes his character as follows :-" Before Mr N. was taken ill in 1832, he was remarkable for mildness of temper ; and, in speaking to his servants, he was kind and civil. At that time, a striking change took place in his temper. In coming into the garden, if he saw a straw or a leaf on the walk, he flew into a

1 On the question, why intoxication excites in a particular manner the organs of Combativeness and Destructiveness, see The Phren. Journ. ix. 306.

COMBATIVENESS. 253

passion. He became extremely irritable towards my father, and at one time struck him ; at another time, he threw a lock at him ; and on a third occasion spat in his face. I felt myself obliged to go out of the way occasionally when I saw him coming, and hid myself among the bushes to avoid him. My father and myself did every thing possible to please him. The same occurrences took place with his other servants, and-1 could give a great many similar examples." In the left posterior lobe of his brain a cavity was found, of two inches in length, lined with a yellowish membrane, into which blood had been effused and afterwards absorbed. Its centre was in Combativeness, but it extended also into Adhesiveness, and a small portion into Philoprogenitiveness. The corresponding portions of the brain on the opposite side of the brain were sound.*

The question here naturally occurs, Why was there in this case excitement of the function from disease of the organ, and almost extinction of the function from diseases of the organs of the domestic affections in the case reported on page 243, under Adhesiveness \ In the present case, there was only effusion of blood, without disorganization of the substance, and the injury was confined to one side of the brain ; while, from the great number of cavities which occurred in the former case, we are led to infer that in it there was destruction, of the organs, and probably on both sides. I may, however, farther remark, that the connection between particular morbid conditions of the brain, and certain morbid manifestations of the faculties, is still little understood. '' Great excitement of the brain," says Dr Combe, "arises from an exhausted as well as from an over-stimulated state of the

* See a full report and discussion of the case in the Phrenological Journal, vol. x. p. 355, 565, 632, 710. This case is reported also in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, No. 129, by a non-phrenological medical practitioner. The reader who will peruse both reports will find that they afford an illustration of a remark previously made in this work, that it is not possible to report, with precision and accuracy, pathological cases of injuries of the brain, so long as the healthy functions of its different parts are unknown.

254 COMBATIVENESS.

system, and is then appeased by food and wine, which, in the opposite state, would be destructive of life. This is seen even in the delirium of fever, which, in the commencement of the disease, is generally caused by excess, and in the later stages more frequently by deficiency of stimulus. Similar phenomena occur in the other organs. Mr Parker mentions several patients in whom epigastric pain aggravated on pressure, strong pulsations, fulness, and all the usual symptoms of inflammatory excitement, were produced by the opposite morbid state, and consequently aggravated by leeches and low diet, while they were cured by wine, nourishing food, and tonics."

This organ is found also in the lower animals ; but there are great differences among them in respect to its energy. Rabbits, for instance, are more courageous than hares ; and one dog looks incessantly for an opportunity of fighting, while another always flies from the combat. The bull-dog forms a contrast in this propensity to the greyhound ; and the head of the former is much wider between and behind the ears than the latter. " This also," says Dr Spurzheim, "is an unfailing sign to recognise if a horse be shy and timid, or bold and sure. The same difference is observed in game-cocks and game-hens, in comparison with domestic fowls. Horse-jockeys, and those who are fond of fighting cocks, have long made this observation." I have frequently verified Dr Spurzheim's remark in regard to horses.

The name given to this faculty by Dr Gall is the instinct of self-defence and defence of property ; but Dr Spurzheim justly regards this appellation as too narrow. " According to the arrangement of nature," says he, " it is necessary to fight in order to defend. Such a propensity must therefore exist for the purposes of defence ; but it seems to me that it is, like all others, of general application, and not limited to self-defence : I therefore call the cerebral part in which it inheres the organ of the propensity to fight or of Combativeness." Mr Robert Cox has published a minute analysis of the faculty in the ninth volume of The Phrenological Jour-

DESTRUCTIVENESS. 255

nal (p. 147), and arrives at the conclusion that, when stripped of all accidental modifications, it is " neither more nor less than the instinct or propensity to oppose, or, as it may be shortly expressed, Opposiveness." He regards " Combativeness," or the tendency to fight, as the result of the combined action of the organ now under discussion,' and that of Destructiveness.

Sir George. Mackenzie, unknown to Mr Cox, had previously expressed a similar view in his Illustrations of Phrenology, published in 1820. " We are inclined," says he, " to consider a propensity to fight as a compound feeling ; and also that desire which some persons appear to have, of being objects of terror to others. A propensity to fight implies a desire to injure. No man can feel a desire to attack another, and say that he has no desire to hurt him." P. 99. Cases illustrative of the organ of Combativeness will be found in The Phrenological Journal, v. 570 ; vii. 638 ; viii. 206,406, 596; ix. 61 ; x. 213 ; xi. p. 333 ; xii. 193 ; xv. p. 56; and on p. 366, a case of excitement of the organ by means of mesmerism.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.