George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

84 GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

BEFORE entering upon the special study of the brain and its functions, it will be useful to give a general idea of the Structure of the nervous system ; and as my object is to introduce non-medical readers to a knowledge of the subject, I shall omit all particulars necessary only for those who purpose studying medicine, for whom professional treatises form the proper source of instruction.

The nervous system consists of the brain and spinal cord, of the nerves which proceed from these organs to the muscles and surface of the body, and of the nervous expansions on the skin and organs of the senses. In other words, it consists of central and peripheral systems, linked together by cords or nerves. When the brain, or any considerable nervous mass, is cut, it is seen to be composed of two different kinds of nervous matter, the gray and the white, and minute examination shews that these two substances are of very different structure. The gray matter, when examined with the microscope, appears to be formed of innumerable granules or minute vesicles, while the white matter is seen to have a tubular or fibrous structure. The gray matter chiefly abounds in the convolutions of the brain ; but it is found also in the nervous structures at the base of the brain, and in the spinal marrow. It is generally regarded by physiologists as the source or generator of nervous power, while the white or tubular matter is considered simply as its conductor. The vesicles of gray matter differ in appearance in different parts of the nervous system ; and it is on very plausible grounds conjectured that on their varying structure the different nervous powers, at least in some degree, depend.

Broadly considered, the functions of the nervous system may be divided into those which subserve the purposes of the mind, and those which in their nature are purely physi-

GENERAL VIEW OF THE 5TERVOUS SYSTEM. 85

cal. It is by means of the former that we have our mental being, our consciousness and volition, while it is through the operation of the latter that we receive the impressions of external objects ; that we move, and breathe, and perform all the physical operations of our body. True, the physical functions are in great measure subject to the control of the mind, but the mental system is still more dependent upon the physical organs ; for it is only through them that the mind is placed in communication with the external world, and that it executes its behests. It is to the physical nervous system that we shall for the moment confine our attention, as the consideration of the organ of the mind will afterwards constitute the chief subject-matter of the present work.

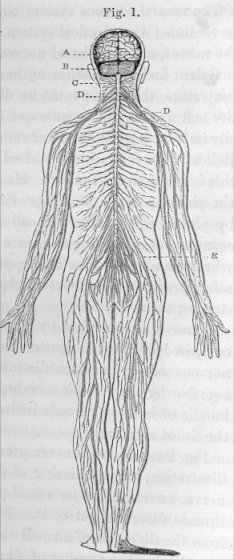

The accompanying figure, though having no pretensions to minute anatomical accuracy, furnishes a good general view of the connection of the different parts of the nervous system. A is the brain, exposed by the removal of the back part of the skull, B the cerebellum, and CC the spinal marrow, which, at its superior extremity,' passes upwards in front of the cerebellum, to join the cerebrum or brain proper.

86 GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

but, on its way, forming a communication also with the cerebellum. D D and E are the nerves proceeding from the spinal cord to the muscles and surface of the body. The nervous expansion on the latter may be considered as represented by the dark line which forms the border of the figure ; and the reality and universality of this expansion is apparent, in the simple fact that it is impossible to pass the point of the finest needle through the skin, without injuring a nerve and producing pain.

The mental nervous system comprises the cerebrum and cerebellum ; the physical system consists of the spinal cord, the nerves, and peripheral nervous expansions.

Galen, and many other authors, long ago published the conjecture, that there must be different nerves for sensibility and for motion, because one of these powers is occasionally impaired, while the other remains entire ; but Sir Charles Bell was the first who furnished demonstrative evidence of this being actually the fact. He also gave due prominence to the philosophical principle previously urgently insisted upon by phrenologists : That, in all departments of the animal economy, each organ performs only one function ; and that wherever complex functions appear, complex organs may be safely predicated, even anteriorly to the possibility of demonstrating them,

A nerve, as described by Sir Charles, is a firm white cord composed of nervous matter and cellular substance. The nervous matter exists in distinct threads, which are bound together by the cellular membrane, and may be likened to a bundle of hairs or threads inclosed in a sheath composed of the finest membrane.

Fig. 2 represents a nerve greatly magnified for the sake of illustration, and consisting of distinct filaments. A is the nerve, enveloped in its membranous sheath ; B one of the threads dissected out of it. The nerves vary in thickness, from the diameter of a small thread to that of a whip-cord, according to the number of fibres included in them. They

GENERAL VIEW 0V THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. 87

are dispersed through the body, and extend to every part which enjoys sensibility or motion, or which has a concatenated action with another part.

When a nerve is examined, there is nothing perceptible in its filaments to distinguish them from each other, or to shew that some are subservient to sensation, and others to motion. It has been proved, however, that some filaments are conductors of a stimulus which produces sensation only, and others of a stimulus which produces motion only ; but this difference of function in the filaments does not depend on any hitherto discerned difference in their structure, but simply on one of relation. A filament of sensation has its origin on a so-called sensitive surface, as on the skin ; it transmits the impression which it here receives inwards to the spinal cord, where a molecular change ensues in certain granules, or vesicles, of the gray matter with which the sensitive filament is associated, the result of which is sensation. A filament of motion, on the contrary, starts from certain other granules of the gray matter of the spinal cord, a molecular change in which imparts a stimulus to the motor filament, which propagates it to the muscles, causing them to contract. Sensation and motion, then, so far as has yet been discovered, are nowise dependent upon the structure of the nerves, but appear to be caused by the central and centripetal relations of the different filaments. A nerve of motion must terminate in a muscle, because it is by muscles only that our movements are performed ; and a nerve of sensation must spring from a sensitive surface, otherwise it could not possibly receive an impression. The filaments of sensation and motion have therefore different centripetal relations or tor-

88 GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

ruinations. In proceeding from the exterior to the interior parts, however, they soon join or coalesce, and then, inclosed in one sheath, appear to form a single nervous cord, and as such pursue their course to the spinal cord. This junction, however, is only a matter of physical arrangement, and is by no means essential to the due performance of the functions of the nerve. We have already seen that one organ performs only one function ; and, in accordance with this principle, we should naturally expect, that the gray matter of the spinal cord which is subservient to motion, should not also be subservient to sensation ; and that therefore the central as well as the centripetal relations of the filaments should be different. This is, in reality, found to be the case. Immediately before reaching the spinal cord, the united nerve of sensation and motion divides, and passes into it by different bundles ; the filaments of sensation becoming associated with the gray matter of the posterior columns, and the filaments of motion with that of the anterior columns.

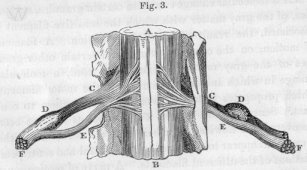

The division of the compound nerve is seen in the accompanying woodcut.

AB represents the spinal marrow seen in front ; the division into lateral portions or columns appearing at the line AB. The compound nerve F divides into E the anterior or motor portion, and C the posterior or sensitive portion, which proceed as described to join the spinal cord

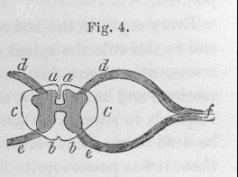

This subject will be further elucidated by the accompany-

GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. 89

ing diagram, which represents a transverse section of the spinal cord.

It is seen to be composed of an Fig. 4. internal gray or vesicular nervous mass, and an external white or fibrous nervous substance, and thus presents the characters both of an originator and a conductor of nervous power. It consists, further, of two symmetrical halves, of which a a form the anterior, and b b the posterior columns; consequently dd constitute the motor, and ee the sensitive branches of the common nerves f f. The middle columns co are composed of fibres, partly motor and partly sentient. But to what, it will now be asked, are we to ascribe this difference of function ? It does not, as we have seen, appear to depend upon any difference in the structure of the nervous filaments, and we must therefore look for it in that of the organs from which those filaments proceed. If we can establish that different nervous functions are dependent on the varying physical structure of the organs, we shall have gained a great step towards establishing the truth of the phrenological doctrines. And that this step has been made, appears from the following passage :- " The difference of structure," says Dr Todd, " of the anterior and posterior horns of the vesicular matter of the spinal cord, may be appropriately referred to as indicating a difference in functions between these horns. The anterior horns contain large caudate vesicles of a remarkable and peculiar kind, containing a considerable quantity of pigmentary matter ; the posterior horns resemble very much in structure the vesicular matter of the cerebral convolutions, and of other parts of the cerebrum, and do not contain caudate vesicles, except near the base. Here, then, we find associated with the well-attested difference in the functions of the anterior and posterior roots, a striking difference in the structure of the anterior and posterior horns of

90 GENERAL VIEW OP THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

the spinal gray matter, in which they are respectively implanted."*

Every organ in the body has its own. independent powers, and to this rule the spinal cord forms no exception. It possesses, as we have just seen, foci of sensation, and foci of motion ; and accordingly, so long as its vitality is kept up, it responds to stimuli, although other organs of the body may be dead or may have been removed. As a nervous centre, then, it has powers quite independent of those of the brain, the functions of which may be destroyed while those of the spinal cord still remain uninjured. We have several means of proving this fact, which at first sight appears in opposition to daily experience. We are so accustomed to consider all the motions of the body as voluntary, that is, as dependent upon cerebral influence, that we are at first at a loss to understand how the muscles should be called into action by means of the action of the spinal cord alone. But this difficulty disappears as soon as it is understood that the spinal cord responds to other stimuli besides that of the will ; and that it really does so, is seen in infants who have been born without brains. Several cases are on record in which the spinal cord, with its continuation, the medulla oblongata were normally developed, but where the brain was entirely wanting. Such infants cried, voided urine and fasces, closed the fingers upon any object placed in their hands ; swallowed the food put into their mouths ; and sucked the breast or fingers. These actions could not be due to volition, for volition is a cerebral function, and must therefore have taken place through means of a physical stimulus. The object placed in the hand, or the finger put to the lips, communicated an impression to the extremities of the nerves of these parts, which was propagated along their trunks to the spinal cord, and there produced a change in the gray matter of the posterior columns of the cord, which the brain under normal circumstances would have recognised as a sensation. But the

*Clyclopodia of Anatomy and Physiology, vol. iii., p. 722, F.

GENERAL VIEW OP THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. 9l

change thus caused is not confined to the gray matter of the posterior columns ; it is propagated or diffused to that of the anterior columns, and thence passes along the motor filaments to the muscles, producing muscular contraction independently of all cerebral influence. Thus muscular motion may be the result of the action of an external physical stimulus, without the brain taking any cognisance of the matter ; and we see this exemplified whenever we tickle the foot of a person asleep. The extremity is withdrawn by means of spinal nervous action, without any intervention of consciousness or of will. In the lower animals, which are much more retentive of life than man, existence is occasionally prolonged for months after removal or destruction of the brain. In such cases, the animal remains in a state of quiescence, as if sunk in deep sleep, till the action of the spinal cord is roused by the application of a stimulus.

A person suffering from an attack of apoplexy is in a position analagous to that of an animal deprived of its brain. The cerebral functions are suspended by the pressure of the blood, and all conscious existence is at an end. Yet the patient moves on being physically irritated, swallows when food is put into his mouth, and continues to breathe for days or weeks in perfect unconsciousness. It is evident, then, that the brain is not the source of muscular nervous power, but is only its conscious director.

The mechanism of motion consists of the spinal cord, nerves and muscles, but the power of conscious guidance resides in the brain.

The physical stimuli which excite the spinal cord to action, vary for different segments of the cord. Its powers or functions are different in kind, and the nature of its excitors varies likewise. And here it may be well to repeat, that under the term spinal cord, we comprehend not only that portion of the nervous centre which is lodged in the vertebral canal, but also its continuation in the skull, till it joins the cerebrum, or brain properly so called. The whole por-

92 GENERAL VIEW OP THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

tion which lies in the vertebral canal responds to the stimulus of touch, that is, of the contact of solid bodies ; but the medulla oblongata, which is the name of the succeeding portion, has acquired a more complex structure, and therewith the power of responding to more subtle stimuli. It constitutes the nervous centre of respiration, and through its action, though in what manner is not yet clearly established, respiration is carried on as an involuntary and unconscious act. The presence of carbonic acid in the air-vessels, or that of black blood in the pulmonary capillaries, is supposed to produce an impression on the extremities of the nerves of the lungs, whereby the medulla oblongata is stimulated to action ; but considerable obscurity still veils the manner in which the respiratory function is performed. Proceeding upwards, we meet with nervous structures which respond to the stimulus produced by sapid substances, by vibrations of the air, by light, and by odours ; thus giving rise to the sensations of taste, hearing, sight, and smell. The nerves of the special senses, accordingly, have their central terminations in structures analogous to those from which the power of common sensation proceeds ; but unlike them, they are unaccompanied in their course by motor filaments. The reason of this deviation in arrangement is obvious. The optic nerve, for instance, carries the stimulus of light to a structure which is solely a sensory ganglion, and from which no motive power emanates ; consequently, any arrangement to bind up the nerve of sight in the same sheath with the motor nerves of the eyeball, coming from distant sources and pursuing various courses, instead of being a convenience, as in the case of the spinal nerves, would have led only to unnecessary complication.

As the mind is conscious of all the impressions which affect the terminations of the nerves and which are propagated to the spinal centres, it is obvious that the brain must have some means of communicating with these centres, so as to receive cognisance of the sensations produced, and be enabled to exercise its control. Accordingly, we find that

GENERAL VIEW OP THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. 93

the fibres of the posterior columns of the cord proceed upwards to the brain, while the anterior fibres proceed downwards. Thus the former constitute the sensitive columns, and the latter the motor columns of the spinal cord ; for all stimuli proceeding upwards must give rise to sensation, and all that proceed downwards must cause motion. Accordingly, when an impression reaches the spinal cord from the skin, the gray matter of the cord is excited, and a knowledge of this excitement is propagated upwards to the brain by means of a filament, which some physiologists regard as a continuation of the identical filament which conveyed the impression from the skin, while others think a new filament springs from the gray matter of the cord to propagate the sensation upwards. - Be this as it may, the excited state of the gray matter is made known to the brain, which thus becomes conscious of the sensation ; and it despatches by the down or motor fibre its mandate to the anterior gray matter, to call into action the muscles necessary for the willed movement.

There are some physiologists, however, of whom Dr Marshall Hall is the chief, who are of opinion that the filaments which transmit impressions from the surface to the brain are entirely distinct from those which convey them to the spinal cord. They consider that two filaments proceed inwards from the periphery, one of which terminates in the gray matter of the cord, while the other continues its course to the brain ; and that two other filaments proceed outwards, one coming from the brain, and the other from the spinal cord. According to this theory, each spinal nerve consists of four different kinds of filaments, of which the two in connexion with the brain constitute the nerves of sensation and voluntary motion ; while the other two constitute the excito-motory system of Dr Marshall Hall, and are supposed to convey impressions from the surface to the spinal cord, and a contractile stimulus from that organ to the muscles, without any intervention on the part of the brain. Thus, the nerves

94 GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

of respiration would be considered as belonging to the excito-motory system. Physiology is not sufficiently advanced to enable us to determine which of these theories is the correct one, but the greater number of its investigators incline to consider the adoption of a distinct set of filaments for the excito-motory functions as an unnecessary complication of structure.

We have adverted to the change produced in the gray matter of the spinal cord by means of a stimulus, as a sensation ; but, strictly speaking, it becomes a sensation only when it is recognised by the brain, for it is through this organ only that we feel. We have retained the term, however, from inability to supply a more suitable word; but the reader will understand that a spinal sensation is not necessarily accompanied by conscious perception.

When we examine that portion of the spinal centres which is lodged in the vertebral canal, we perceive that it is not of uniform thickness, but that it swells out in the region which gives origin to the nerves of the upper and lower extremities. This fact is in accordance with the law, that, coteris paribus, size is a measure of power. The gray matter of the cord is especially increased, for it is upon it, as we have seen, that the spinal powers chiefly depend. This arrangement is uniformly found throughout the whole animal kingdom, and is particularly well seen in birds of great power of flight, in which the spinal cord at the origin of the nerves of the wings, acquires a comparatively large development.

The sensitive and motor filaments are not equally distributed in the compound nerves, but vary accordingly as the chief functions of the nerve are sensation or motion. Thus, according to Desmoulins, the sensitive fibres of the upper extremities of man, are much more numerous than the motor fibres, while the reverse is the case in the lower extremities. It is scarcely necessary to point out how completely this arrangement is in accordance with the respective functions of the organs. Few persons, who have not reflected on the sub-

GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. 95

ject, are aware to how great an extent the harmonious action of the sensitive and motor functions of the nerves is reciprocally dependent. But, in reality, so much is this the case, that an animal deprived of sensation, though retaining its motor powers entire, would probably perish from hunger, through inability to feel its food. In one of his experiments, Sir Charles Bell cut that division of the fifth nerve which goes to the lips of an ass. The sensibility of the lips was in consequence destroyed, so that when the animal pressed them against its oats, it did not feel them, and thus made no effort to gather them. When, on the other hand, the seventh nerve was cut, the motive power of the lips was destroyed ; and then, though the animal felt the oats, it made no effort to gather them, from inability to contract the muscles. A man who has been deprived of sensation by disease, may to a certain extent direct his movements by the eye, but as soon as it is averted, he loses control over his muscles, and stumbles in walking, or drops whatever he may hold in his hand.

When a nerve of motion is injured, motive power is lost, because the stimulus to contract no longer reaches the muscles ; but when a sensitive nerve is cut, though the part which was supplied by the nerve loses its sensibility, sensation is still conveyed to the brain by the part of the nerve situated above the injury. All sensations are perceived in the brain, and thus a stimulus, though in the normal state always applied to the peripheral extremities of the nerves, may, in abnormal conditions, be perceived when affecting the cut extremities of nerves. Thus, individuals who have suffered amputation of a limb, frequently fancy that they still perceive sensations in their toes or fingers, and this arises from some irritation of the divided filaments of the nerve whose branches formerly supplied these portions of the amputated limb. Or sensation may be perceived, or imagined, through disease of the central ganglia of sensation, without the application of any stimulus whatever to the nerves. In this way imaginary sounds are heard, imaginary visions seen

96 GENERAL VIEW OP THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

and imaginary odours perceived, giving rise to what are called hallucinations. Occasionally, when the brain is healthy, the subject of these phenomena recognises their abnormal origin, and does not allow his actions to be determined by them ; but frequently the power of correctly appreciating their origin is destroyed. In this case the imaginary sensations are not distinguished from normal nervous action, and the patient acting upon them becomes virtually insane.

Hitherto we have spoken only of the cerebro-spinal system- of nerves, as constituting that which alone interests us in our present inquiry ; but it may be well, in order to prevent misunderstanding, to say a few words on the sympathetic or ganglionic nervous system. This system is generally supposed to preside over the functions of nutrition, and hence it receives also the name of the system of organic life, in contradistinction to that of animal life, which is bestowed upon the cerebro-spinal system. Its operations are entirely beyond our control, though it is affected by certain mental conditions. It is by its means that the heart contracts and circulates the blood, and that the bowels propel their contents. Over these functions, it is well known, we exercise no volition ; but nevertheless, we are all familiar with the fact, that they are occasionally greatly influenced by the state of the mind. The nervous ganglia of the system of organic life consist of numerous small bodies, about the size of peas or beans, which are situated in different parts of the body, but chiefly in the chest and abdomen, and from which filaments issue to be distributed to the various thoracic and abdominal organs. They are composed of gray matter, and thus constitute independent nervous centres. It is supposed that the blood and the contents of the bowels afford a stimulus to the sensitive nervous filaments distributed on the heart and alimentary canal, and that this is reflected back from their respective ganglia as a motor stimulus. The true nature and mode of action of the ganglionic system, however, are still very imperfectly known, and it would not accord with our present purpose to pursue the subject further.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.