J.G. Spurzheim, The Anatomy of the Brain, with a General View of the Nervous System. Translated at the request, and under the immediate superintendence of the author from the unpublished French M.S. by R[obert] Willis, MRCS, London, 1826. [Preface & plates only]

In

this work Spurzheim made bold claims about

what he represented as his own discoveries and techniques in the anatomy of

the brain. How much he in fact borrowed from F.J.

Gall, his long term master, is yet to be demonstrated. Spurzheim also

reproduced in this work portions of text written by Gall in his earlier work.

Below are the 11 plates, many of which Spurzheim took from the 1812 atlas

to Anatomie et physiologie du système nerveux published together

with Gall.

In

this work Spurzheim made bold claims about

what he represented as his own discoveries and techniques in the anatomy of

the brain. How much he in fact borrowed from F.J.

Gall, his long term master, is yet to be demonstrated. Spurzheim also

reproduced in this work portions of text written by Gall in his earlier work.

Below are the 11 plates, many of which Spurzheim took from the 1812 atlas

to Anatomie et physiologie du système nerveux published together

with Gall.

The preface, reproduced below, provides interesting details about Spurzheim's

relations with Gall and claims to independence from the shadow of the more

famous Gall.

Compare Spurzheim's plates with those from William Carpenter's Principles of mental physiology, 1874, Appendix pp. 709-722.

-------------------------

PREFACE.

_____

THE affective and intellectual faculties of man, both in their

healthy and diseased condition, are unquestionably dependent on the body ;

and, among the various branches of anthropology, anatomy is the basis of all

the others. The organic apparatuses, which are indispensable to the mental

manifestations, consist of the brain, cerebellum, spinal cord, and the nerves

of the external senses and voluntary motion. To make known the structure of

these parts is the special object of this volume.

History proves that the structure and destination of the nerves were long

unknown. Hippocrates and Aristotle, for instance, confounded, under the same

general title, ligaments, tendons, nerves, and even blood-vessels. Hippocrates

believed that the nerves terminated in muscles and bones, and produced voluntary

motion. Herophilus, who lived nearly three centuries before the com-

viii PREFACE.

mencement of the vulgar era, was the first who discovered the

connexion of the nerves with the brain, and who looked on them as the instruments

of sensation. Erasistratus divided the nerves into those of sensation and

those of motion; the first he derived from the brain, the second from the

membranes. Galen held that the nerves of sensation arose from the brain, and

those of voluntary motion from the spinal cord. In the sixteenth and succeeding

centuries the brain and nerves were subjects of much research, but it is only

in our own times that they have begun to be understood,-that their true structure

has been discovered, and that new and unthought-of functions have been proved

to belong to them.

The nervous being the most delicate tissues of the body necessarily required

extremely careful and often-repeated examination to be understood, and this

they could not receive during ages when prejudice opposed insurmountable obstacles

to the dissection of dead bodies. It is therefore easy to conceive why such

slow progress was made in the anatomical knowledge of the nervous system.

PREFACE. ix

Dr. Gall is the original author of a new physiological doctrine

of the brain. The discovery of the ground-work of this is all his own, and

he had even gone very far in rearing the superstructure before the year 1804,

when I became his colleague. From this period we continued labouring in common,

until 1813, when our connexion ceased, and each began to pursue the subject

for himself. The works which Dr. Gall has published in his own name fix the

extent of his phrenological knowledge. My ideas, too, are developed in my

own publications: history will assign to each of us his share in the works

that have issued under our joint names.

It was in the year 1800 that I attended for the first time the private course

of lectures which Dr. Gall had been in the habit of delivering occasionally

at his house for four years. At this time he spoke of the necessity of the

brain to the manifestations of mind, of the plurality of the mind's organs,

and of the possibility of discovering the development of the brain by the

configuration of the head. He pointed out several particular organs of different

memories, and of several sentiments, but he had not yet begun to examine the

X PREFACE.

structure of the brain*. Between 1800 and 1804 he modified his

physiological ideas and brought them- to the state in which he professed them

at the commencement of our travels.†

Dr. Gall haying met with a woman, fifty-four years of age, who from her infancy

had laboured under dropsy of the brain, and who, nevertheless, was as active

and intelligent as the generality of females in her own rank of life and being

convinced that the brain was the indispensable organ of the soul, expressed

himself in terms similar to those which Tulpius had used before him, on observing

a person afflicted with hydrocephalus, who exhibited good intellectual faculties,

viz., the structure of the brain must be different from what it is commonly

supposed to be. He now felt the necessity of examining the mind's organ anatomically.

As his medical practice occupied his time, he employed M. Niclas, a student,

to dissect for him ; but the

* Exposition de la Doctrine de Gall, par Froriep, 3me edit,

1802.

† Bischoff Exposition de la Doctrine de M. Gall, sur le Cerceau et le

Crane, Berlin, 1805 ; et Blœde, la Doctrine de Gall Sur les fonctions

du Cerveau, Dresden, 1805,

PREFACE. XI

spirit of this gentleman's researches was merely mechanical,

as is allowed in our joint work, entitled " Anatomie et Physiologie du

Systeme nerveux en général, et du Cerveau en particulier*."

Having completed my studies in 1804, I was associated with Dr. Gall, and devoted

myself especially to anatomical inquiries. At this period, Dr. Gall, in the

Anatomy, spoke of the decussation of the pyramidal bodies, of their passage

through the pons Varolii, of eleven layers of longitudinal and transverse

fibres in the pons, of the continuation of the optic nerve to the anterior

pair of the quadrigeminal bodies, of the exterior bundles of the crura of

the brain diverging beneath the optic nerves in the direction which Vieussens,

Monro, Vicq d'Azyr, and Reil† had followed, the first, by means of scraping,

the others, by cutting the substance of the brain. Dr. Gall shewed further,

the continuation of the anterior commissure across the striated bodies ; he

also spoke of the unfolding of the brain that happens in hydrocephalus. The

notion he had conceived of this, however,

* Preface to the first vol. p 16.

† Gren's Journal, 1795, i. p. 102.

b 2

xii PREFACE.

was not correct ; for he thought that the convolutions resulted

from the duplicature of a membrane, believing that the cerebral crura entered

the hemispheres on one side, expanded there, and then folded back on themselves

by the juxtaposition of the convolutions. The true structure of the convolutions,

and their connexion with the rest of the cerebral mass, were not described

until our joint Memoir was presented to the French Institute in 1808.

The mechanical direction which the anatomical investigations had taken did

not appear to me satisfactory. Guiding myself in my inquiries by physiological

views, always comparing structure with function, I discovered the law of the

successive additions to the cerebral parts ; the divergence in every direction

of the crural bundles towards the convolutions ; the difference between the

diverging fibres and those of union ; the generality of commissures ; the

true connexion of the convolutions with the rest of the cerebral mass, and

the peculiar structure which admits of the convolutions being unfolded (an

event that occurs in hydrocephalus of the cavities), whilst the mass lying

at their bot-

PREFACE. xiii

toms, and belonging, for the most part, to the apparatus of

union, or of the commissures, is pushed by the water between the two layers

composing them ; lastly, I demonstrated the structure of the nervous mass

of the spine, and I flatter myself with having arrived at the best method

of dissecting the brain, and exposing its parts.

What is my object then in publishing this volume ? Our large work is too expensive

for the generality of medical students, and, further, the method pursued in

the discussions there is only calculated for professed anatomists; whilst

this book will be both less costly, and it will be adapted to the student

as well as to the more advanced anatomist. Moreover, many new ideas, possessing

a great share of interest, may now be added; for since Dr. Gall and I first

published, the study of the nervous system has engaged the especial attention

of anatomists and physiologists. I have, myself, continued inquiring, and

conceive that I have made several new discoveries. I have, however, copied

some passages from the first volume of the large work already mentioned, and

also given reduced drawings of several of its

xiv PREFACE.

plates because I think I have acquired a right to this volume,

by its publication in our joint names, by my discoveries that form its principal

object, and by all I did in furtherance of its publication. All the drawings

were executed under my superintendence from anatomical preparations, made

and determined on by me ; the engraver worked by my directions ; no plate

was sent to press without my approval; the descriptions of the plates, and

the anatomical details are mine ; and I furnished the literary notices in

regard to the nerves of the abdominal thorax, to those of the cerebral column,

of the five senses, of the cerebellum, and of the brain.

Whoever desires more copious historical details than this volume will be found

to contain, I refer to our Memoir, addressed to the French Institute, and

to the first volume of our great work, commenced in common, and continued

by Dr. Gall singly, after the middle of the second volume.

The influence our labours have had on the study of the nervous system is incontestable.

To be convinced of this, it is enough to examine the state of knowledge in

regard to the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the

PREFACE. xv

brain and spinal marrow, when Dr. Gall and I developed our ideas on these matters, whether it was by teaching orally, by dissecting publicly, or by means of our writings. I confess there is great satisfaction in the consciousness of having contributed to the important reform that has been effected in regard to the nervous system. I am only sorry to observe, that many of our ideas are appropriated by the authors of recent publications, without any mention of the source whence they were derived, or of the individuals who first struck them out, or reduced them to certainty by direct proofs. We are commonly enough mentioned, it is true, when such of our assertions as appear weak are the subjects of criticism, but our names are kept in the background when points of importance become the matter of discussion. The public, for instance, by referring to the proper place, may judge whether Mr. J. Cloquet, in his "Anatomy of Man," has been sufficiently explicit in stating, that he has copied every one of the plates of the human brain contained in our large work. M. Serres, whose Memoir was deemed worthy of its prize by the Academy of Sciences of

PREFACE. xvi

Paris, in the first volume of his work, uses our names no fewer

than fifteen times, in connexion with a single idea, which he fancies he can

refute; and generally along with every fact that looks unfavourable to our

opinion, he names us, but he always forgets to cite us in relation to very

many fundamental conceptions which we had announced at the same time. They

who have written to the following effect:—" M. Serres has proved

clearly the erroneousness of M. Gall's observations, and replaced them by

others," may undeceive themselves by attending to the remark I have just

made.

M. Serres's publication forces me likewise to request the reader to distinguish

between a multitude of words and facts on the one hand and the corollaries

which result on the other. I agree with those who, in works of science, pay

especial regard to truths demonstrable to others, to ideas available in practical

life, and to clearness and simplicity of style. To what purpose may serve

the following passage, which occurs in the preliminary discourse of M. Serres,

where, after having said that a monster may be a vegetation of its like, that

it may have,

PREFACE. xvii

two heads, two tails, and six or eight extremities, but that

it would remain strictly confined to the limits of its class, he exclaims

:—" This wonderful phenomenon is undoubtedly connected with the

general harmony of creation. What may be its cause ? We know it not, and in

all likelihood we shall remain ignorant of it for ever. It is one of the mysteries

of creation, whose surface is meted by man, but whose depths are sounded,

and known to God alone *."

This phenomenon does not appear to me more extraordinary than that a kitten

is not a puppy, or that the crab-tree does not produce pears. If the egg of

a bird in its ordinary state cannot produce a mammiferous animal, why should

the germ of this same egg, if it chance to be imperfectly developed, produce

a deformity like to one of the mammalia ? Were the case thus, there would

be some cause for an amazement, but the universal fact of every animal producing

its kind,

* " Cet étonnant phénomène est sans doute hé à l'harmcmîe générale de la création. Quelle peut en être la cause ? Nous l'ignorons et vraisemblablement nous l'ignorerous toujours. C'est un des mystères de la création, dont l'homme mesure la surface, mais dont Dieu &eul sonde et counatt la profondeur."

xviii PREFACE.

is not, in my eyes, more astonishing than any other natural

event.

Further, the mass of facts cited, the number of dissections made, ought never

to impose on us, nor be made a means of concealing the truth. Many of the

anatomists who had lived before us dissected some hundreds of brains, and

they made a boast of their doings in this way ; but they did not perceive

that which I pledge myself to have discovered before I had dissected a dozen

; for instance, the successive additions to the cerebral parts, and the two

kinds of fibres, to wit, the diverging, and the fibres of union. Anatomists

and physiologists had certainly looked upon heads without number ; but before

Dr. Gall's appearance, had failed to discover the seat of a single cerebral

organ. A solitary individual, a beggar, enabled him to detect the organ of

self-esteem, precisely as the fall of a single apple revealed the law of gravitation

to Newton. Anatomists had seen many human brains without remarking any differences

among them; these, however, are, to say the least, as constant as similarities.

The point that essentially interests science is, the

PREFACE. xix

discovery of the truth, and this is then confirmed and established

by all ulterior observations.

The anatomy of the peculiar system necessary to the affective and intellectual

manifestations, as well as anatomy in general, admits of consideration in

several ways.

First, it is simply descriptive, that is, physical appearances alone are examined,

such as the form, the size, and colour of parts, the tissues which compose

them, and their connexions.

The nomenclature of the encephalon, of itself suffices to shew that such views

had principally guided anatomists in their study of its structure. We still

speak of the brain, of the cerebellum, of hemispheres, lobes, convolutions,

and anfractuosities ; of a fornix, an infundibulum or funnel, and of pisiform

and striated, and quadrigeminal and pyramidal, and olivary and harrow-shaped

bodies ; of a pineal gland, of a hippocampus's foot, of a writing-pen, and

many other parts, some with very offensive names. Such views are easily conceived

to be but little useful in medicine. This is the reason why the gene-

xx PREFACE.

ality of practitioners are satisfied with knowing the membraneous

envelopes of the encephalon the large blood-vessels, the sinuses, the great

masses of the brain and cerebellum, and the principal cavities. Of these views,

however, I shall only take such notice as may be necessary to recognize the

parts spoken of in my physiological and pathological considerations.

M. Serres, in the first page of his work on the Anatomy of the Brain, says,

"Up to the present time, (1824,) no one has dreamt of uniting into a

body of doctrine all the knowledge acquired on the anatomy, the physiology

and the pathology of the brain and nervous system. I enter on the attempt

to overtake this vast subject *." Dr. Gall's and my own works belie this

assertion, and they have only to be consulted to prove that all our inquiries

were directed into this very channel. We have constantly insisted on the importance

of studying the nervous system under all relations at once. From the year

1817 to 1823,

* "Jusqu'à ce jour (1824) personne n'a songé à rCunir en corps de doctrine les connaissances acquises sui Panatomie, la physiologie et la pathologie du system nerveux. Je vais essaye de parcourir ce vaste sujet."

PREFACE. xxi

I regularly delivered " a Course of Lectures on the Anatomy,

Physiology, and Pathology of the Brain and External Senses," twice a

year. My course was always so announced, according to the custom in Paris,

by public placards ; and my auditors must recollect that in my introductory

discourse, I uniformly insisted on the importance and necessity of studying

these branches in connexion. From the above, it will be evident that M. Serres

was mistaken when he published himself " the first to attempt to overtake

(essayer de parcourir) this vast subject." Nevertheless, I most willingly

allow that the principal consideration is not the having been the first to

examine the nervous system : the true merit of the inquirer consists in that

which he has effected, that which he had discovered, and justice in these

particulars will, in time, be assuredly tendered to all. If, on occasion,

I seem more especially solicitous in shewing the erroneousness of M. Series's

opinions, it is only because these have received the sanction of the French

Institute, whose influence is great over the public mind.

2. Anatomy is physiological, when the

xxii PREFACE.

structure of parts is studied in relation to their functions.

This kind of anatomical knowledge is essential to practical medicine ; for

without it, the seat of deranged functions cannot be understood. For this

reason, therefore, my anatomical details will always be given in harmony with

the physiological ideas I entertain of the apparatus destined to the manifestation

of the affective and intellectual faculties.

3. Anatomy is peculiarly human, or, it comprehends the other beings of creation.

In the latter event, it is entitled comparative anatomy, and this is a field

that possesses much interest for the anatomist, physiologist, ana practical

physician; I shall, therefore, enter upon it at frequent intervals, always

with the view of advancing the knowledge on the affective and intellectual

nature of man.

4. Anatomy is entitled pathological, when it treats of the organic changes

undergone by parts whether examined in connexion with, or independently of,

their deranged functions. Inquiries in this direction belong less to the present

volume, than to that I have published

PREFACE. xxiii

on Insanity. To it, therefore, I refer the reader for details.

The object of this compendium, then, is to present the principal views that

may be taken of the physiological and comparative anatomy of the apparatus

destined to the affective and intellectual manifestations. It will be found

divided into nine sections:—in the first, I make some general reflections

on the nervous system ; in the second, I speak of the division of the nervous

apparatuses ; in the third, I treat of the nerves of voluntary motion and

of the external senses; in the fourth, I discuss the best mode of examining

the structure of the brain ; in the fifth, I describe the cerebellum particularly

; in the sixth, I do the like in regard to the brain; in the seventh, I examine

the commissures ; in the eighth, the communication of the nervous parts with

each other ; and in the ninth, I go into some anatomical points connected

with physiology. The work will prove that I rather adhere to philosophical

views and principles, than to mere description of the physical qualities belonging

to individual masses, although this last be the most common, I might almost

say

xxiv PREFACE.

the only plan that is generally pursued. I have endeavoured, in an especial manner, to class together the parts that constitute particular apparatuses, a practice which to our predecessors was entirely unknown, as is abundantly evident from their nomenclature of the brain and its parts.

--------------------------

PLATES:

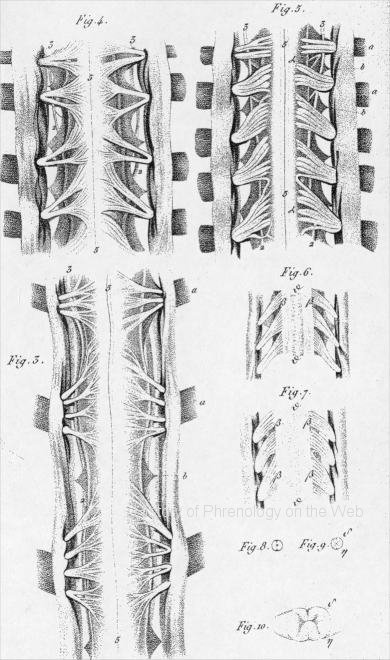

PLATE I.

Fig. I. Four ganglions, with their branches of communication, of the caudal

extremity of a caterpillar. This arrangement of the nervous system reigns

through, the entire length, of the body of caterpillars and worms.

Fig. 2. The caudal extremity of the spinal marrow of a fowl, with, the oiigin

of the three last pairs of doi'sal nerves.

Fig. 3. The three superior cervical pairs of nerves in a calf, seen on the

abdominal surface. The dura mater and arachnoid are slit longitudinally

and turned aside, so as to expose the mode in which the nervous filaments

come from the common mass, their different directions, and the passage of

the bundles through the duia mater. The commencement of the intervertébral

ganglions (a) is covered by the reflected membranes. Between the different

pairs of nerves, the teeth of the ligamentum dentatum (e) are seen on each

side of the nervous mass ; these ligaments separate the abdominal fiom the

dorsal roots, and are attached to the dura mater by means of slips, naturally

different in size and position. At the origin of each pair of nerves, a

swelling is perceivable, varying in magnitude, ia proportion to the volume

of the issuing nerve.

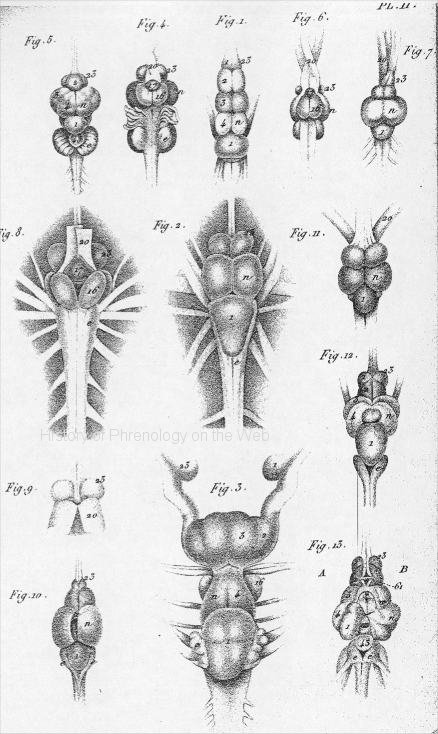

PLATE II. -Brains of Fishes

Fig. 1. The brain of an eel seen from above.

Fig. 2. The brain of a cod seen from above.

Fig. 3. The brain of a skate seen from above.

Fig, 4 The brain of a carp seen, from below.

Fig. 5, The brain of a carp seen from above.

Fig. 6. The brain of a Sounder seen from below.

Fig, 7, The brain of a Sounder seen from above,

Fig. 8. The brain of a cod seen from below.

Fig 9. The optic nerves in the cod are thrown back, to permit a view of

the two roots of the olfactory nerves.

Fig. 10, The brain of a pike, -with the cavity of the optic ganglion exposed.

Fig. 11. The brain of a roach.

Fig, 12. The brain of a barbel seen from above.

Fig, 13. The interior of the brain of barbel, prepared to permit a view

of the ganglions, their cotajnunications, and junctions.

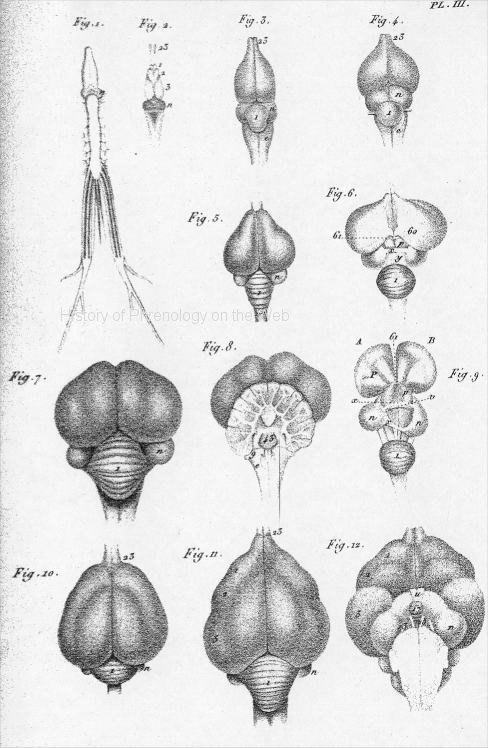

PLATE III. -Brains of Reptiles and of Birds.

Fig. 1. The spino-cerebial system of a frog seen from below.

Fig. 2. The brain of a frog seen from above.

Fig, 3. From M, Carus's work.-The brain of a lizard (lacerta. iguana) seen

from above.

Fig.4. From M. Carus's work- the brain of a young crocodile seen from above.

Fig.5. The brain of a common fowl seen from above. .

Fig. 6. The brain of a fowl,- The two hemispheres separated. to shew the cerebellum,

the optic .ganglions, 'their commissure, the commencement of the supposed

optic thalimai and the part analogous to the fornix of the mammalia.

Fig. 7. The brain of a turkey seen from above.

Fig.8. The brain of a turkey with the cerebellum cleft-posteriorly, to shew

its lamellar structure,

Fig. 9. The brain of a common fowl, prepared to shew the cavity of the optic

ganglion, the posterior commissure, - the .beginning and continuation of the

great cerebral ganglions.

Fig.10. The brain of a duck seen fcom above.

Fig. 11. The brain of a goose seen from above.

Fig, 12. The brain of a goose seen from below.

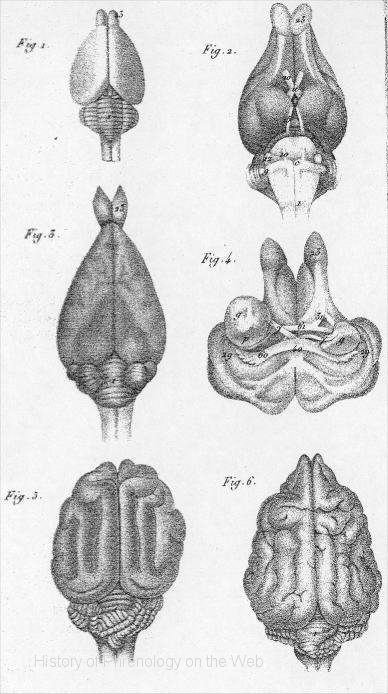

PLATE IV. -Brains of Mammiferous Animals.

Fig. 1. The brain of myrmesophaga didactyla seen from above,

copied from the work of Tiedemann.

Fig. 2. The brain of a hare seen from below.

Fig, 3. The brain of a hare seen from above.

Fig. 4. The brain of a liare placed on its upper .snriaee, like Fig 2; the

mass below the crura cerebri is cut off ; the crura are separated and pushed

sidewards, to see the under surface of posterior lobes; the fornix, 60; the

posterior fold of the corpus callosum, 40: .the anterior pillar of the fornix

y ; the anterior commisure, 61, .and, its two portions.

Fig. 5. The brain of a cat seen from above.

Fig. 6. The brain of a dog seen from above. All are reduced to the fourth

of their natural size.

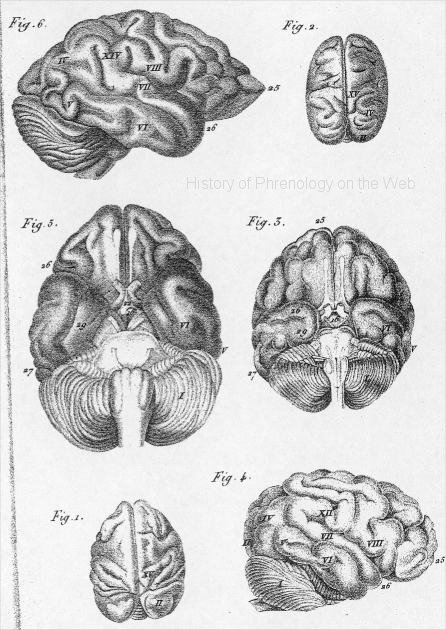

PLATE V.

[The brains and their parts, represented in this plate, and all preparations of the human brain, in the following plates, are only a fourth of their natural size.]

Fig 1. The brain of the monkey, simia saboea, seen from above,

Fig. 2. Tke brain of the monkey, sinnia capucina, seen from above.

Fig. 3. The brain of the ourang-outang seen from below.

Fig. 4. The brain of the ourang-outang seen from the right side.

Fig, 5. The brain of an idiotic girl seen from below.

Fig. 6. The same brain of the idiotic girl seen from the right side.

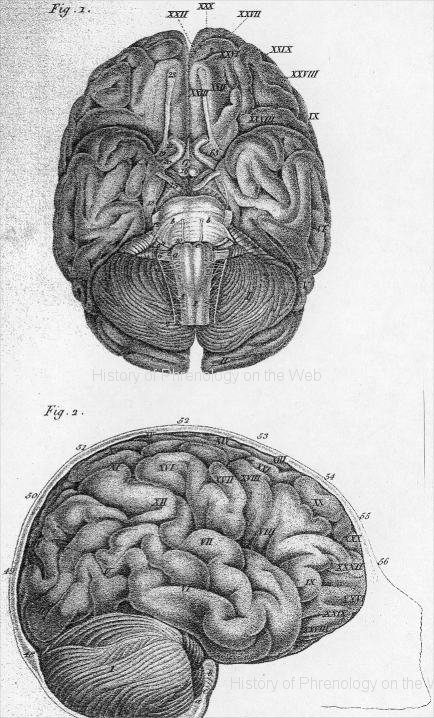

PLATE VI.

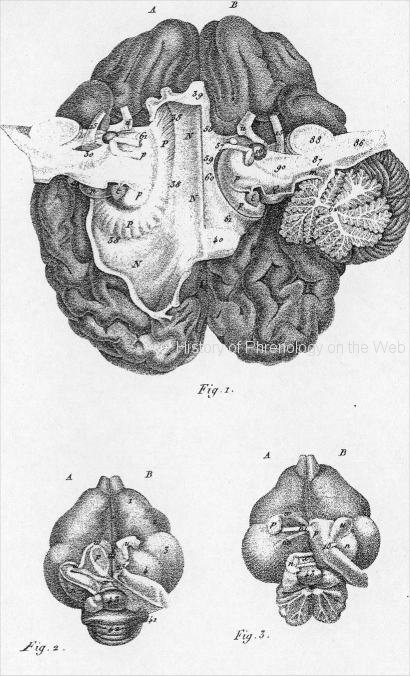

Fig. I. The Basis of the human brain. - All the parts are in

pairs, but not quite symmetrical. The brain is taken from the skull, and turned

on its upper surface; the cerebellum and medulla oblongata have fallen backwards

; the different investing membranes are removed ; the cerebral and nervous

masses alone are visible.

To take-the human brain from the skull, I make an incision from one ear to

the other, turn the integuments backwards and forwards, and detach the temporal

muscles from, the bone. If it is requisite to preserve the skull, it must

be saved about three-quarters of an inch above the superciliary ridge, round

on each, side to the middle of the occipital bone...

Fig, 2. A skull sawed vertically tbrough the middle of the forehead, the vertex

and the occiput to expose the exterior and lateral surface of the brain, cerebeîlom,

aii-ular protuberance, and medulla oblongata in their Batural situations,

The bone here supports the cerebellum and medulla oblongata, whilst in Fig.

1 they had downwards and backwards.

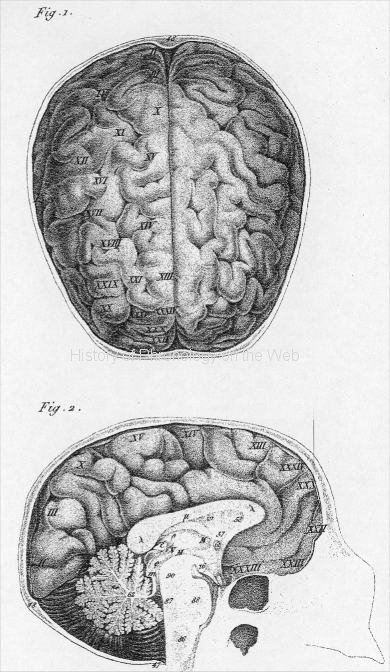

PLATE VII.

Fig. 1. A skull sawed honsontally in a line from the eye-brows,

by tlie middle oi t fee temples, add the tipper part of the occipital borie.

The membranes and blood-vessels are removed, and the two hemispheres are seen

from above.

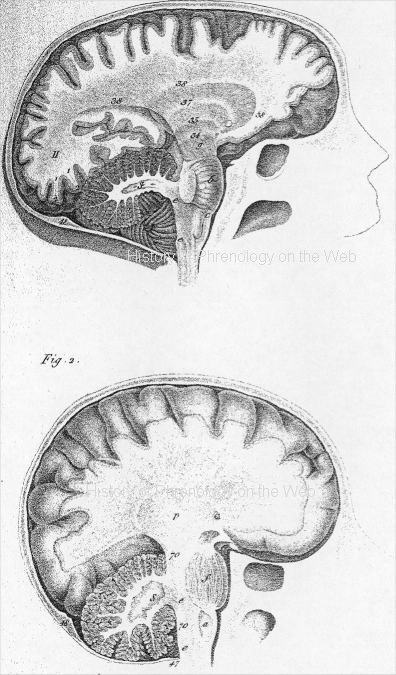

Fig. 2, The skull, brain, and cerebellum cut vertically through the median

line and in their natural situations. In this preparation the various parts

are retained in their proper places, not without considerable difficulty.

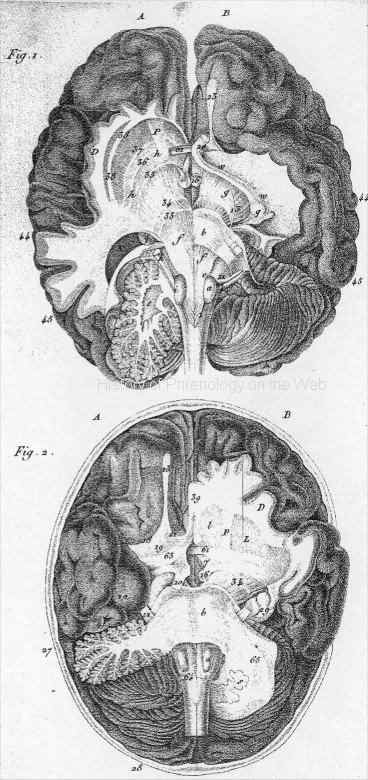

PLATE VIII.

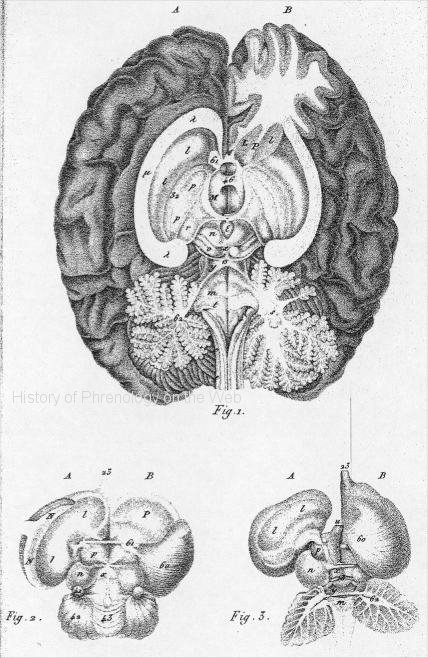

Fig, 1. A preparation exhibiting various parts about the base

of the brain.

...

PLATE IX.

Fig. 1. The cranium sawed on the right side; the cut passes

vertically by the middle of the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, and by

the right orbit- The great union of the cerebellum, b, is cut transversely

behind the exit of the trigeminal nerve, and the external part of the cerebellum

is removed. ...

Fig. 2. The cranium sawed perpendicularly in the middle line of the head.

...

PLATE X.

Fig. 1. The brain laid on its superior surface.

PLATE III.

Fig. 1. The human brain laid on its base. ...

----------------------------------------------

See some additional brain images in Combe's System of Phrenology (1853).

Compare Gall and Spurzheim's engravings to those of earlier anatomists.

Vesalius, De Humani Corporus fabrica (1543).

Thomas Willis, De Anima Brutorum (1672).

For more images: Franz Joseph Gall - Johann Gaspar Spurzheim - The Combe brothers

On the brain see especially: GENERAL VIEW OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM in Combe, System of phrenology, 1850, Carpenter, Principles of mental physiology, 1874, Appendix pp. 709-722.

------------------------

RN3

Digital text and digital images are copyright John van Wyhe 2002.

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.