Combe, George. 1847. The Constitution of Man and Its Relation to External Objects. Edinburgh: Maclachlan, Stewart, & Co., Longman & Co.; Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., W. S. Orr & Co., London, James M'Glashan, Dublin.

Scanned, OCRed and corrected by John van Wyhe 1999. Reformated 8.2006. RN1

[page ii]

THE

CONSTITUTION OF MAN

CONSIDERED IN

RELATION TO EXTERNAL OBJECTS.

BY

GEORGE COMBE.

"Vain is the ridicule with

which one foresees some persons will divert

themselves, upon finding lesser pains

considered as instances of divine pun-

ishment. There is no possibility of

answering or evading the general thing

here intended, without denying all

final causes."—Butler's Analogy

EIGHTH EDITION,

REVISED, CORRECTED, AND ENLARGED.

EDINBURGH :

MACLACHLAN, STEWART, & CO.

LONGMAN & CO.; SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO.;

W. S. ORR & CO., LONDON.

AND JAMES M'GLASHAN, DUBLIN.

--

MDCCCXLVII

[page iii]

------

PRINTED BY NEILL AND COMPANY, EDINBURGH

[page iv]

ADVERTISEMENT

TO THE EIGHTH EDITION.

______________

The First Edition of the present Work was published

in June 1828; and since that time there have

been printed the following numbers:—

I. Editions in Duodecimo,

11,500

II. The Peoples Edition, in double columns,

royal 8vo, published at 1s. 6d. per Copy, 67,000

III. The School Edition, 12mo, at 1s. 6d.

boards, 1,000

IV. The present Edition, post 8vo. 1,000

Total, 80,500

Numerous editions have been printed

also in the

United States of North America, while translations

have appeared in the French, German, and Swedish

Languages.

These facts seem to indicate that it has been

received

with increasing favour, in proportion as it

has been studied.

The present edition has been revised, corrected,

and

enlarged.

45 Melville Street, Edinburgh

1st July 1847.

[page v]

HENDERSON BEQUEST.

On 27th May 1829, the late W. R. Henderson, Esq. younger of Warriston and Eildon Hall, executed a deed of settlement, by which he conveyed to certain trustees such funds as he should die possessed of; and, in the event of his dying without leaving children, he appointed them to pay certain legacies and annuities to individual friends, and gave the following instructions regarding the application of the residue of his funds. "And, lastly, the whole residue of my means and estate shall, after answering the purposes above written, be applied by my said trustees in whatever manner they may judge best for the advancement and diffusion of the science of Phrenology, and the practical application thereof in particular; giving hereby and committing to my said trustees, the most full and unlimited power to manage and dispose of the said residue, in whatever manner shall appear to them best suited to promote the ends in view: Declaring, that if I had less confidence in my trustees, I would make it imperative on them to print and publish one or more editions of an 'Essay on the Constitution of Man considered in relation to External Objects, by George Combe,'—in a cheap form, so as to be easily purchased by the more intelligent individuals of the poorer classes, and Mechanics' Institutions, &c. ; but that I consider it better only to request their particular attention to this suggestion, and to leave them quite at liberty to act as circumstances may seem to them to render expedient ; seeing that the state of the country, and things impossible to foresee, may make what would be of unquestionable advantage now, not advisable at some future period of time. But if my decease shall happen before any material change affecting this subject, I request them to act agreeably to my suggestion. And

[page] vi HENDERSON BEQUEST.

I think it proper here to declare, that I dispose of the residue of my property in the above manner, not from my being carried away by a transient fit of enthusiasm, but from a deliberate, calm, and deep-rooted conviction, that nothing whatever hitherto known can operate so powerfully to the improvement and happiness of mankind, as the knowledge and practical adoption of the principles disclosed by Phrenology, and particularly of those which are developed in the Essay on the Constitution of Man, above mentioned." Mr Henderson having died on 29th May 1832, his Trustees carried his instructions, in regard to the present work, into effect; but, since 1835, it has not been necessary to make any demand on his funds for printing it in any of its forms. 1st July 1847.

[page] vi HENDERSON BEQUEST.

PREFACE.

________

This Work would not have been presented to the Public, had I not believed that it contains views of the constitution, condition, and prospects of Man, which deserve attention. But these, I trust, are not ushered forth with anything approaching to a presumptuous spirit. I lay no claim to originality of conception. My first notions of the natural laws were derived from a manuscript work of Dr Spurzheim, with the perusal of which I was honoured in 1824, and which was afterwards published under the title of "A Sketch of the Natural Laws of Man, by G. Spurzheim, M.D." A comparison of the text of it with that of the following pages, will shew to what extent I am indebted to my late excellent and lamented master and friend for my ideas on the subject. All my inquiries and meditations since have impressed me more and more with a conviction of their importance. The materials employed lie open to all. Taken separately, I would hardly say that a new truth has been presented in the following work. The parts have nearly all been admitted and employed again and again, by writers on morals, from the time of Socrates down to the present day. In this

[page] viii PREFACE

respect, there is nothing new under the sun. The only novelty in this work respects the relations which acknowledged truths hold to each other. Physical laws of nature, affecting our physical condition, as well as regulating the whole material system of the universe, are universally acknowledged to exist, and constitute the elements of natural philosophy and chemical science: Physiologists, medical practitioners, and all who take medical aid, admit the existence of organic laws: And the sciences of government, legislation, education, indeed our whole train of conduct through life, proceed upon the admission of laws in morals. Accordingly, the laws of nature have formed an interesting subject of inquiry to philosophers of all ages ; but, so far as I am aware, no author hitherto attempted to point out, in a systematic form, the relations between those laws and the constitution of Man ; which must, nevertheless, be done, before our knowledge of them can be beneficially applied. Dr Spurzheim, in his "Philosophical Principles of Phrenology," adverted to the independent operation of the several classes of natural laws, and pointed out some of the consequences of this doctrine, but without entering into detailed elucidations. The great object of the following treatise is to exhibit the constitution of Man, and its relations to several of the most important natural laws, with a view to the improvement of education, and the regulation of individual and national conduct.

But although my purpose is practical, a theory of

[page] PREFACE ix

Mind forms an essential element in the execution of the plan. Without it, no Comparison can be instituted between the natural constitution of man and external objects. Phrenology appears to me to be the clearest, most complete, and best supported system of mental philosophy which has hitherto been taught; and I have assumed it as the basis of this work. But the practical value of the views to be unfolded does not depend entirely on Phrenology. The latter as a theory of Mind, is itself valuable only in so far as it is a just exposition of what previously existed in human nature. We are physical, organic, and moral beings, acting under general laws, whether the connection of different mental qualities with particular portions of the brain, as taught by Phrenology, be admitted or denied. Individuals, under the impulse of passion, or by their direction of intellect, will hope, fear, wonder, perceive, and act, whether the degree in which they habitually do so be ascertainable by the means which it points out or not. In so far, therefore, as this work treats of the known qualities of Man, it may be instructive even to those who contemn Phrenology as unfounded; while it can prove useful to none, if the doctrines which it unfolds shall be found not to be in accordance with the principles of human nature, by whatever system these may be expounded.

Some individuals object to all mental philosophy as useless, and argue, that, as Mathematics, Chemistry, and Botany, have become great sciences without the

[page] x PREFACE

least reference to the faculties by means of which they are cultivated; so Morals, Religion, Legislation, and

Political Economy, have existed, have been improved, and may continue to advance, with equal success, without any help from the philosophy of mind. Such objectors, however, should consider that lines, circles, and triangles-earths, alkalies, and acids—and also corollas, stamens, pistils, and stigmas,—are objects which exist independently of the mind, and may be investigated by the application of the mental powers, in ignorance of the constitution of the faculties themselves—just as we may practise archery without studying the anatomy of the hand; whereas the objects of moral and political philosophy are the qualities and actions of the mind itself:—These objects have no existence independently of mind; and they can no more be systematically or scientifically understood without the knowledge of mental philosophy, than optics can be cultivated as a science in ignorance of the structure and modes of action of the eye.

I have endeavoured to avoid religious controversy. "The object of Moral Philosophy," says Mr Stewart, "is to ascertain the general rules of a wise and virtuous conduct in life, in so far as these rules may be discovered by the unassisted light of nature; that is, by an examination of the principles of the human constitution, and of the circumstances in which man is placed."* By following this method of inquiry, Dr

* Outlines of Moral Philosophy, p. 1.

[page] PREFACE xi

Hutcheson, Dr Adam Smith, Dr Reid, Mr Stewart, and Dr Thomas Brown, have, in succession, produced highly interesting and instructive works on moral Science; and the present Treatise is an humble attempt to pursue the same plan, with the aid of the new lights afforded by Phrenology. I confine my observations exclusively to Man as he exists in the present world, and beg that, in perusing the subsequent pages, this explanation may be constantly kept in view. In consequence of forgetting it, my language has occasionally been misapprehended, and my objects misrepresented. When I speak of man's highest interest, for example, I uniformly refer to man as he exists in this world.

Since the last edition of this work appeared, on 9th June 1828, additional attention has been paid to the study of the laws of nature, and their importance has been more generally recognised.

Edinburgh, 45 Melville Street,

1st July 1847.

[page xii]

[page xiii]

CONTENTS.

---

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS.

General view of the constitution of human nature, and its relations to external objects, . . 1-28

Light thrown by geology on the physical history of the globe before the creation of man, page 1—Death and reproduction appear to have existed before his creation, 4—The world arranged so as to afford him every inducement to cultivate and exercise his understanding, 6—Power of man to control and turn to account the capabilities of the physical world, 6—Barbarism and civilization compared, 7—Progressive improvement of man apparent from history. 8—Reason for anticipating a future increase of the happiness and intelligence of the race, 11—Causes of man's slow progress, 11—Mental Philosophy hitherto very imperfect, 12—Theologians have neglected the order of nature, 13—Constitution of the human mind, and its adaptation to the external world, not expounded in the Bridgewater Treatises, 15—Natural laws, physical, organic, and moral 18—The independent operation of these, very important in relation to the moral government of the world, 19—Definition of "natural law," 20—Objections answered, 22-23—Physiological preliminaries of moral and religious conduct must exist before Preaching can produce its full effects, 25.

CHAPTER I.

ON NATURAL LAWS, . . . . 28-45

Man's faculties capable of ascertaining what exists, and the purpose of what exists, but not the will of the Deity in creation, p. 28—All the departments of Nature have definite constitutions and fixed laws imposed by the Deity, 29—The term law defined and illustrated, 29—Man's pleasure and pain depend, in this world, upon observance of, and obedience to, these constitutions and laws; an opinion supported by Bishop Butler, 32—The Natural Laws di-

[page] xiv CONTENTS.

vided into Physical, Organic, and Moral, and obedience or disobedience to each asserted to have distinct effects; while the whole are universal, invariable, unbending, and in harmony with the entire constitution of man, 35—Death in certain circumstances appears desirable, 40—Benevolence not the exclusive or immediate, but the ultimate, principle on which the world is arranged, 41—Evil in no case the ultimate, but only in certain instances the immediate, principle, and that for wise and benevolent ends, 43—The will of the Deity in designing evil inscrutable, but the mental constitution shewn by Phrenology to bear relation to it, 44.

CHAPTER II.

ON THE CONSTITUTION OF MAN, AND ITS RELATIONS TO EXTERNAL

OBJECTS, . . . . . . 45-97

The constitution of man, on the principle of a subjection of the whole to reflection and the highest sentiments, shewn by Bishop Butler to be conformable to the constitution of the external world, p. 45—(1.) Man considered as a physical being, and the evils resulting from breach of the physical laws shewn to be only exceptions from the benefits habitually flowing from those laws, 47—(2.) Man considered as an organised being, and the rules for the enjoyment of a sound body explained, 49—(3.) Man considered as an animal, moral, and intellectual being, and his mental constitution detailed, 56—(4.) The mental faculties compared with each other, 62—The propensities designed for good, when acting harmoniously with, and guided by, the higher sentiments and intellect; otherwise lead to evil, 64—True happiness of individuals and societies found ultimately to consist in a habitual exercise of the higher sentiments, intellect, and propensities, in harmony with each other, 79—(6.) The faculties of man compared with external objects, and the means of their gratification specified, 87.

CHAPTER III.

ON THE SOURCES OF HUMAN HAPPINESS, AND THE CONDITIONS REQUISITE FOR MAINTAINING IT, . 97-113

All enjoyment arises from activity of the different parts of the human constitution, p. 97—Creation so arranged as to invite and encourage exercise of the bodily and mental powers, 95—The acquisition of knowledge agreeable, 99—Would Intuitive knowledge be more advantageous to man, than the mere capacity which he has received to acquire knowledge by his own exertions? 100—Reasons for answering this question In the negative, 101—To reap enjoyment in the greatest quantity, and maintain it most permanently, the faculties must be gratified in harmony with

[page] CONTENTS. xv

each other, 110—Reasons for believing that the laws of external creation will, in the progress of discovery, be found accordant with the dictates of all the faculties of man acting in harmonious combination, 111.

CHAPTER IV.

APPLICATION OF THE NATURAL LAWS TO THE PRACTICAL ARRANGEMENTS OF LIFE, . . . . 113-127

Suggestion of a scheme of living and occupation for the human race, p. 113—Every day ought to be so apportioned as to permit of (1) bodily exercise; (2) useful employment of the intellectual powers (3) the cultivation and gratification of the moral and religious sentiments; (4) the taking of food and sleep-Gratification of the animal faculties included in these, 116—Why has man made so little progress towards happiness? 118—A reply to this question very difficult—Dr Chalmers quoted on the subject, 119—Has man advanced in happiness in proportion to the increase of his knowledge? 121—his progress retarded by ignorance of his constitution, and its adaptation to external objects, 122—The experience of past ages affords no sufficient reason for limiting our estimate of mans capability of civilization, 123—Recent date of some of the most important scientific discoveries, and imperfect condition of most branches of human knowledge, 124.

CHAPTER V.

TO WHAT EXTENT ARE THE MISERIES OF MANKIND REFERABLE TO INFRINGEMENTS OF THE LAWS OF NATURE? 127-331

SECTION I.

Calamities arising from Infringement of the Physical Laws.

These laws of great utility to animals who act in accordance with them, and productive of injury only when disregarded—Example of law of gravitation, p. 128—Man and the lower animals constitutionally placed in certain relations to that law, 129—Calamities suffered from it by man, to what referable? 130—The objection considered, That the great body of mankind are not sufficiently moral and intellectual to act in conformity with the natural laws, 131—The more ignorant and careless men are, the more they suffer, 133.

SECTION II

Evils that befall Mankind from Infringement of the Organic Laws, 133

Necessity of so enlightening the intellect as to enable it to curb and

[page] xvi CONTENTS.

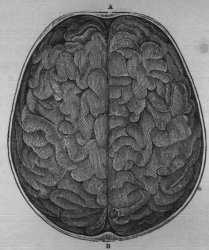

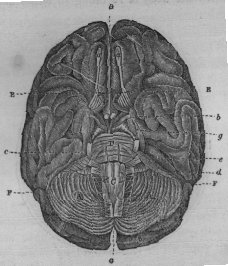

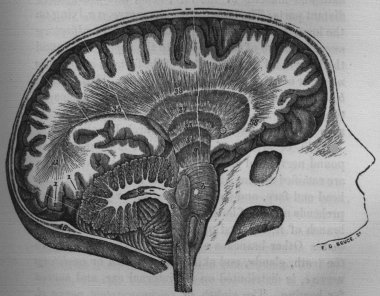

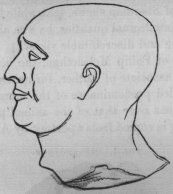

direct the blind feelings which naturally and spontaneously arise in the mind, 134—Organised being defined, 135—A constitution as perfect as possible, must spring from a sound and complete germ; be supplied with food, light, and air; and duly exercise. its function, 135—The human frame so constituted as to admit of the possibility of health and vigour during a long life—Remarkable health of the New Zealanders, 136—The sufferings of women in childbed apparently not inevitable, 137—The organic laws hitherto neglected and little known, 138—Miseries resulting from this cause to INDIVIDUALS, 139—Description of the brain, 142—Necessity for its regular exercise, 148—To provide for this, we must (1) educate and train the mental faculties in youth, and (2) place individuals in circumstances habitually demanding the discharge of useful and important duties, 150—Answer to the question, What is the use of education? 150—The whole body improved by exercise of the brain, 151—Misery of idleness, 153—Instances of evils produced by neglect of the natural laws: The great plague in London, 155; fever and ague in marshy districts, explosions in coal-mines, 157—Answer to the objection, That men are unable to remember the natural laws, and to apply the knowledge of them in practice, 158—Advantage of teaching scientific principles, 160—Farther examples of disease and premature death consequent on neglect of the organic laws, 162—Eminent success of Captain Murray in preserving the health of his crew, 164 ; additional cases, 168—Obedience to natural laws a duty, 170—Erroneous views of some religious writers, 174.

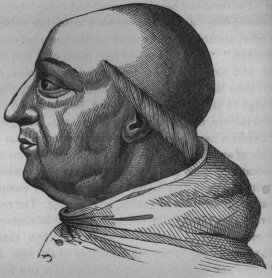

Social miseries from neglect of the organic laws, 177—(1) Domestic miseries—Marriage of persons with discordant minds a fertile source of unhappiness—Phrenology affords the means of avoiding this error—Different forms of head, and the concomitant dispositions, exemplified by the cases of Hare, Williams, Sheridan, Melancthon, and Pope Alexander VI., 178—Crabbe and Dr Johnson quoted, 186—Hereditary transmission of bodily and mental qualities from parents to children—Transmission of diseases well known—Transmission of character remarked by many writers —Horace, Drs John and James Gregory, Voltaire, Dr King, Dr Mason Good, Haller, &c., quoted on this subject, 188—Hereditary descent of forms of brain obvious in nations, 193—The offspring of an American or Asiatic and a European superior to the offspring of two Americans or Asiatics, 194—The extent to which children resemble their parents, considered—Reasons for concluding that the mental character of each child is determined by the qualities of the stock, combined with the faculties predominant in the parents at the commencement of its existence, 196—Transmission of factitious or temporary conditions of the body, 197—Transmission of acquired habits, 198—Appearance of peculiarities in children, in consequence of impressions made on the mind of the mother, 200—Descent of temporary mental and bodily qualities, 203—These subjects still in many respects obscure, 209—General neglect of the organic laws in the formation

[page] CONTENTS. xvii

of marriages, 211—Dr Caldwell quoted, 212—Marriage prohibited in Wurtemberg before certain ages, 214—Advantages arising from the law of hereditary descent, and bad effects which would follow its abolition, 215—Why do children of the same marriage differ from each other? 222—Cases illustrative of the evils resulting from neglect of the law of hereditary transmission, 223—Marriage between blood-relations forbidden by the natural law, 226—(2) hurtful consequences of neglect of the organic laws In the ordinary relations of society, 228—Misconduct of servants, clerks, partners, and agents, 228—Utility of Phrenology in enabling us to avoid this source of misery, 231—Death—A natural and useful institution, 233—Views of theologians respecting it, 236—Death considered as it affects the lower animals, 237; and mankind, 246—Nature does not seem to intend the death of human beings, except in old age, 248—Means provided by nature to relieve men from the fear of death, 251—Death not revolting to the moral sentiments, 252—Frequency of premature death decreasing, 254.

SECTION III.

Calamities arising from Infringement of the Moral Law, 256

Cause of the diversity of moral and religious codes and opinions in different nations and among philosophers, 257—Advantages secured by cultivating and acting under the dictates of the moral sentiments and intellect, 259; and evils induced by the opposite conduct, 263—(1) Sufferings of individuals from neglect of the moral and intellectual laws, 270—(2) Calamities arising to individuals and communities from infringement of the social law, 272—Malthus's principle of population, 270—The inhabitants of Britain too much engrossed by manufacturing and mercantile pursuits, 277—Misery produced by overstocking the markets, 278—Times of "commercial prosperity" are seasons of the greatest infringements of the laws of nature, 284—Injustice and inexpediency of the combination laws, 284—Necessity of abridging the periods of labour of the operative population, and cultivating their moral and rational faculties, 288—This rendered possible by the use of machinery in manufactures, 290—Ought government to interfere with industry? 294—Miseries endured by the middle and upper ranks in consequence of departure front the moral law in the present customs of society, 300—(3) Effect of the moral law on national prosperity, 302—The highest prosperity of one nation perfectly compatible with that of every other, 304—Evil produced by disregard of these principles Illustrations in the project of Themistocles to burn the Spartan ships, the slave-trade, and the American war, 305—England, 307—Rome, 309—Other evils from the same source, 310—Bad effects anticipated from the existence of negro slavery in the United States, 320—The Spaniards punished under the natural laws for their cruelties in America, 324—The civilization of savages more

[page] xviii CONTENTS.

easy by pacific than by forcible measures, 325—Moral science far outstripped by physical, 327—Necessity of cultivating the former, 328—India, 328.

CHAPTER VI.

ON THE EVIL CONSEQUENCES CONNECTED WITH INFRINGING THE

NATURAL LAWS, . . . . . 331

SECTION I.

On Suffering as inflicted under the Natural Laws, 331

Laws may be instituted either for the selfish gratification of the legislator, or for the benefit of the governed, p.331—Gessler's order to the Swiss, an instance of the former, 332; the natural laws of God, of the latter, 333—The object of punishment for disobedience to the divine laws is to arrest the offender, and save him from greater miseries, 334—Beneficial effects of this arrangement—Laws of combustion; advantages attending them, and mode in which man is enabled to enjoy these and escape from the danger to which he is subjected by fire, 335—Utility of pain, 335—Suffering under the natural laws have for their object to bring the sufferers back to obedience for their own welfare, and to terminate their misery by death when the error is irreparable, 339—Punishments mutually inflicted by the lower animals, 341—Punishments mutually inflicted by men, 343—Criminal laws hitherto framed on the principle of animal resentment, 344—Inefficacy of these, from overlooking the causes of crime, and leaving them to operate with unabated energy after the infliction, 346—Moral in preference to animal retribution, suggested as a mode of treatment, 346—Every crime proceeds from an abuse of some faculty or other—The question, Whence originates the tendency to abuse? answered by the aid of Phrenology, 349—Crime extinguishable only by removing its causes, 351—The effects of animal and moral punishment compared, 362—Remarks on the natural distinction between right and wrong, 358—The objections considered, That, according to the proposed moral system of treating offenders, punishment would be abrogated and crime encouraged, 360 ; and That the author's views on this subject are Utopian, and in the present state of society, impracticable, 362.

SECTION II.

Moral advantages of Suffering,

The mental improvement of man not the primary object for which suffering Is sent, 364—Errors of some religions sects adverted to, 366—Bishop Butler teaches, more rationally, that a large proportion of our sufferings is the result of our own misconduct, 366—The objection, that sufferings are often disproportionately

[page] CONTENTS. xix

severe, considered, 367—Recapitulation of the advantages flowing from obedience, and misfortunes from disobedience, to the moral laws, 368.

CHAPTER VII.

ON THE COMBINED OPERATION OF THE NATURAL LAWS, 370-397

Accidents and misfortunes, view of, p. 370—Combined operation of the natural laws illustrated by reference to the defects of the arrangements for jury trial in Scotland, 372—The great fires in Edinburgh in 1824, 375—Shipwrecks from ignorance or irrational conduct in the commander, 379—Captain Lyon's unsuccessful attempt to reach Repulse Bay, 385—Foundering of decayed and ill-equipped vessels at sea, 393—And the mercantile distress which overspread Britain in 1825-26, 394—Laws which regulate human conduct, 395—Can we evade the natural laws? 396.

CHAPTER VIII.

INFLUENCE OF THE NATURAL LAWS ON THE HAPPINESS OF INDIVIDUALS. . . . 398-411

The objection considered, that although, when viewed abstractly, the natural laws appear beneficent and just, yet they are undeniably the cause of extensive, severe, and unavoidable suffering to individuals—Their justice and benevolence, In reference to individuals, illustrated by imaginary cases of suspension of various physical, organic, and social laws, viz., case of the slater, p. 398—The husbandman, 401—The young heir, 405—The afflicted child, 407—The merchant, 408.

CHAPTER IX.

ON THE RELATION BETWEEN RELIGION AND SCIENCE, 413-442

Importance of religion, p. 412—Difference between religion and theology, 412—The religious sentiments may be directed towards the enforcement of obedience to God's natural laws, 413—Great influence of the moral and religious sentiments, 414—Science an exposition of the course of God's secular providence, 415—Objection considered, 417—Men act on their views, right or wrong, of God's secular providence, 418—Necessity of having their principles of actions reconciled with their principles of belief; 415—Necessity of a new Reformation in religion, 418—Examples in Which the religious sentiments might advantageously have been called in to give practical efficiency to dictates of science,—viz.

[page] xx CONTENTS.

In abating the mortality of Exeter, 420—of Edinburgh and Leith. 424—The precepts of Christianity are, and must be, supported and enforced by the natural laws, otherwise they cannot become practical, 426—Illustrations drawn from the history of Ireland, 426—from convict management, 428—Nature and causes of the efficacy of "moral force," 429—Illustrations drawn from Irish agitation for repeal of the Union, 430—from repeal of the corn-laws, 431—Insufficiency of purely doctrinal education to enable men to understand and obey the natural laws, 434—Illustrations drawn from the history of Ireland, 435—Effects of purely doctrinal teaching and of teaching the natural laws, on practical conduct, contrasted, 438—Experience does not disprove the existence of a moral government of the world by God, 439—Scripture doctrines relating to eternity left to clerical teaching, 441.

CHAPTER X.

CONCLUSION, . . 443-461

What is the practical use of Phrenology, even supposing it to be true? p. 443—Its utility pointed out in reference to politics, 445, legislation, 446, education, 446, morals and religion, 449, and the professions, pursuits, hours of exertion, and amusements of individuals, 450—The precepts of Christianity impracticable in the present state of society, 451—Improvement anticipated from the diffusion of the true philosophy of mind, 445—The change, however, will be gradual, 457—What ought education to embrace? 458—and what religious instruction ? 459.

---

APPENDIX.

No. I. Natural Laws, Text, p. 33 . . . 463

II. Muscular Labour, Text, p. 56,... 468

III. Sulphuric Ether and Child-bed, Text, p. 138... 470

IV. Hereditary Descent of National Peculiarities, Text, p. 194, ....471

V. Hereditary Complexion, Text, p. 203, ... 472

VI. Hereditary Transmission of Qualities, Text, p. 207, . 473

VII. Laws Relative to Marriage and Education in Germany, Text, p. 214, . . 485

VIII. Death, Text, p. 256, . . . . . . . . 489

IX. Object of the Author of Nature in instituting Suffering and Death, Text, p. 334, . 494

X. On Suffering Inflicted under the Natural Laws, Text, p. 336 . . 499

XI. On Religion, Text, p. 412, . . . . 502

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS.

___________

GENERAL VIEW OF THE CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE AND ITS RELATIONS TO EXTERNAL OBJECTS.

The science of Geology aims at giving an exposition of the changes which the crust of the earth and its inhabitants have undergone since the original formation of the globe, and it treats of conditions of things which must have existed long anterior to the dates of human records. The causes of the phenomena which it describes, are still subjects of discussion; but a great mass of well authenticated facts concerning the Condition of the globe itself and of its early inhabitants, has been collected, which may fairly be regarded as solid scientific truth. The facts bear a relation to the subject of the present work, in so far as they proclaim that these important changes had taken place in the crust of the globe and among its inhabitants, before Man appeared. All the solid materials of the earth have been in a gaseous or fluid condition, and

A

[page] 2 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

what is now dry land has been at the bottom of the ocean. The remains of myriads of plants and animals are found entombed in the rocks the clay and the soil, without the slightest traces of man's contemporaneous existence.

However startling the results of geological investigations may appear, the records which establish them are too authentic and precise to leave room for doubt as to their substantial truth. "There is no limit," says Professor Ansted,* "to the number and variety of the remains of animal and vegetable existence. At one time we see before us, extracted from a solid mass of rock, a model of the softest, most delicate, and least easily preserved parts of animal structure; at another time the actual bones, teeth, and scales, scarcely altered from their condition in the living animal. The very skin, the eye, the foot-prints of the creature in the mud, and the food that it was digesting at the time of its death, together with those portions that had been separated by the digestive organs as containing no nutriment, are all as clearly exhibited as if death had, within a few hours, performed its commission, and all had been instantly prepared for our investigation. We find the remains of fish so perfect, that not one bone, not one scale, is out of place or wanting, and others, in the same bed, presenting only the outline of a skeleton, or various disjointed fragments. We have insects, the delicate nervines of whose wings are permanently impressed upon the stone in which they are embedded; and we see occasionally shells, not merely retaining their shape, but perpetuating their very colours,—the

* Geology, introductory, descriptive, and practical, by David Thomas Ansted, M.A., F.R.S., &c., 1844. Vol. 1., p. 53.

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE 3

most fleeting, one would think, of all characteristics,—and offering evidence of the brilliancy and beauty of creation at a time when man was not yet an inhabitant of the earth, and there seemed no one to appreciate the beauties which we are perhaps too apt to think were called into existence only for our admiration." In regard to the causes of these phenomena, Sir Humphrey Davy conceived the globe to have been originally a fluid mass, with an immense atmosphere revolving in space around the sun. By its cooling, it became, says he, gradually condensed, and at length dry land and sea appeared. Five successive races of plants, and four successive races of animals, he believed to have been created and swept away, before the system of things became so permanent as to fit the world for man.*

In opposition to these views, Mr Lyell in his Principles of Geology,† chap. IX., maintains that "the popular theory of the successive development of the animal and vegetable world, from the simplest to the most perfect forms, rests on a very insecure foundation," and that the changes in the condition of the globe, brought to light by geological investigations, may, in the present state of our knowledge, be referred to causes still in operation. More recently the author of the work entitled "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation," endeavours to shew that the primitive formation of the globe was the result of the well known laws of physics, and that even the organic world has been developed under the

* The Last Days of a Philosopher, by Sir Humphrey Davy, 1831, p. 134.

† Seventh Edition, 1847.

[page] 4 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

care of the Deity, not by special interferences, but in manner of natural law.*

In reference to the object of the present work, it is not necessary to decide on the merits of these different hypotheses. All geological authorities agree in representing physical nature as having undergone a variety of changes, and having at length attained to the condition which it now presents, before man occupied its surface. "I need not dwell," says Mr Lyell, "on the proofs of the low antiquity of our species, for it is not controverted by any experienced geologist." "It is never pretended that our race co-existed with assemblages of animals and plants, of which all or even, a large proportion of the species are extinct." P. 143.

"In all these various formations," says Dr Buckland, the coprolites" (or the dung of the Saurian reptiles in a fossil state, exhibiting scales of fishes and other traces of the prey which they had devoured) "form records of warfare waged by successive generations of inhabitants of our planet on one another; and the general law of nature, which bids all to eat and be eaten in their turn, is shewn to have been co-extensive with animal existence upon our globe, the carnivora in each period of the world's history fulfilling their destined office to check excess in the progress of life, and maintain the balance of creation."

* The views of this author have been objected to as excluding the influence of the Deity in the universe; but Bishop Butler remarks, that "If civil magistrates could make the sanctions of their laws take place without interposing at all after they had passed them, without a trial and the formalities of an execution; if they were able to make their laws execute themselves, or every offender to execute them upon himself, we should be just in the same sense under their government as we are now; but in a much higher degree and more perfect manner." If this argument be admitted, the hypothesis of the author of the Vestiges cannot logically be considered as denying the influence of the Divine Will on the universe.

[page]CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 5

It is thus admitted by the most esteemed authorities, that death and reproduction formed parts of the order of nature before man can be traced on the globe.

Let us now contemplate Man himself, and his adaptation to the external creation. The order of creation seems not to have been changed at his introduction, but he appears to have been adapted to it. He received from his Creator an organized structure, and animal instincts. The brain is unquestionably the workmanship of God, and there exist in it organs of faculties which impel man to kill that he may eat, to oppose aggression, and to shun danger,—impulses related to a constitution of nature similar to that which is conjectured to have existed prior to his introduction. Man, then, apparently took his station among, yet at the head of, the beings that inhabited the earth at his creation. He is to a certain extent an animal in his structure, powers, feelings, and desires, and is adapted to a world in which death reigns, and generation succeeds generation.

This fact, although so trite and obvious as to appear scarcely worthy of being noticed, is of importance in treating of Man; because the human being, in so far as he resembles the inferior creatures, is capable of enjoying a life like theirs: he has pleasure in eating, drinking, sleeping, and exercising his limbs; and one of the greatest obstacles to improvement is, that many of the race are contented with these enjoyments, and consider it painful to be compelled to seek higher sources of gratification. But to the animal nature of man have been added, by a bountiful Creator, moral sentiments and reflecting faculties, which not only place him above all other creatures on earth, but constitute a different being from any of them, a rational and accountable being. These faculties are his best and

[page] 6 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

highest gifts, and the sources of his purest and intensest pleasures. They lead him directly to the great objects of his existence,—obedience to God, and love towards his fellow-men. But this peculiarity attends them, that while his animal faculties act powerfully of themselves, his rational faculties require to be cultivated, exercised, and instructed, before they will yield their full harvest of enjoyment.

The Creator has so arranged the material world as to hold forth strong inducements to man to cultivate his higher powers. The philosophic mind perceives in external nature, a vast assemblage of stupendous powers, too great for the feeble hand of man entirely to control, but kindly subjected, within certain limits, to the influence of his will. Man is introduced on earth apparently helpless and unprovided for, as a homeless stranger; hut the soil on which he treads is endowed with a thousand capabilities of production, which require only to be excited by his intelligence to yield him ample returns. The impetuous torrent rolls its waters to the main; but as it dashes over the mountain-cliff, he is capable of withdrawing it from its course, and rendering its powers subservient to his will. Ocean extends over half the globe her liquid plain, in which no path appears, and the rude winds oft lift her waters to the sky; but there the skill of man may launch the strong-knit bark, spread forth the canvas to the gale, and make the trackless deep a highway through the world. In such a state of things, knowledge is truly power; and it is highly important to human beings to become acquainted with the constitution and relations of every object around them, that they may discover its capabilities of ministering to their advantage.

Where these physical energies are too powerful to be

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 7

controlled man has received intelligence by which he may observe their courses of action, and accommodate his conduct to their influence. This capacity of adaptation is a valuable substitute for the power of regulating them by his will. He cannot arrest the sun in its course, so as to avert the wintry storms, and cause perpetual spring to bloom around him; but, by the proper exercise of his intelligence and corporeal energies, may foresee the approach of bleak skies and rude winds, and place himself in safety from their injurious effects. These powers of applying nature, and of accommodating his conduct to her course, are the direct results of his rational faculties; and in proportion to their cultivation is his sway extended. Man, while ignorant, is a helpless creature; but every step in knowledge is accompanied by an augmentation of his power.

Again: We are surrounded by countless beings inferior and equal to ourselves, whose qualities yield us the greatest happiness, or bring upon us the bitterest evil, according as we affect them agreeably or disagreeably by our conduct. To draw forth all their excellencies, and cause them to diffuse joy around us—to avoid touching the harsher springs of their constitution, and bringing painful discord to our feelings—it is necessary that we should know their nature, and act with a habitual regard to the relations established by the Creator between them and ourselves.

Man, ignorant and uncivilized, is cruel, sensual, and superstitious. The world affords some enjoyments to his animal feelings, but it confounds his moral and intellectual faculties. External nature exhibits to his mind a mighty chaos of events, and a dread display of power. The chain of causation appears too intricate

[page] 8 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

to be unravelled, and the power too stupendous to be controlled. Order and beauty, indeed, occasionally gleam forth to his eye from detached portions of creation, and seem to promise happiness and joy; but more frequently, clouds and darkness brood over the scene, and disappoint his fondest expectations. Nature is never contemplated with a clear perception of its adaptation to promote the enjoyment of the human race, or with a well founded confidence in the wisdom and benevolence of its Author.

Man, on the other hand, when civilized and illuminated by knowledge, discovers, in the objects and occurrences around him, a scheme beneficently arranged for the gratification of his animal, moral, and intellectual powers; he recognises in himself the intelligent and accountable subject of a bountiful Creator, and in joy and gladness desires to study the Creator's works, to ascertain his laws, and to yield to them a steady and a willing obedience. Without undervaluing the pleasures of his animal nature, he tastes the higher, more refined, and more enduring delights of his moral and intellectual capacities; and he then calls aloud for education, as indispensable to the full enjoyment of his powers.

If this representation be correct, we perceive the advantage of gaining knowledge of our own constitution and of that of external nature, with a view to regulating our conduct according to rules drawn from such information. Our constitution and our position equally imply, that we should not remain contented with the pleasures of mere animal life, but that we should take the dignified and far more delightful station of moral and rational occupants of this lower world.

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 9

The civil history of man proclaims the march, although often vacillating and slow, of moral and intellectual improvement. To avoid too extensive an inquiry, unsuitable to an introductory discourse, let us confine our attention to the aspects presented by society in our native country.

At the time of the Roman invasion, the inhabitants of Britain lived as savages, and appeared in painted skins. After the Norman conquest, one part of the nation was placed in the condition of serfs, condemned to labour like beasts of burden, while the other devoted itself to war. The nobles fought battles during the day, and in the night probably dreamed of bloodshed and broils. Next came the age of chivalry, These generations severally believed their own condition to be the highest, or at least the permanent and inevitable lot of man. Now, however, have come the present arrangements of society, in which millions of men are shut up in cotton and other manufactories for ten or twelve hours a-day; others labour under ground in mines; others plough the fields; while thousands of higher rank pass their whole lives in frivolous amusements. The elementary principles, both bodily and mental, were the same in our painted ancestors, in their chivalrous descendants, and in us, their shop-keeping, manufacturing, and money-gathering children. Yet how different the external circumstances of the individuals of these several generations! If, in the savage state, the internal faculties of man were in harmony among themselves, and his external condition was in accordance with them, he must then have enjoyed all the happiness of which his nature was capable, and must have erred when he changed it;—if the institutions and customs of the age of chivalry

[page] 10 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

were calculated to gratify his whole nature harmoniously, he must have been unhappy as a savage, and must be miserable now;—if his present condition be the perfection of his nature, he must have been far from enjoyment, both as a savage and as a feudal warrior;—and if none of these conditions have been in accordance with his constitution, he must still have his happiness to seek.

Every age, accordingly, has testified that it was not in possession of contentment; and the question presents itself,—If human nature has received a definite constitution, and if one arrangement of external circumstances be more suited to yield it gratification than another, what are that constitution and that arrangement? No one among the philosophers has succeeded in informing us.—If we in Britain have not reached the limits of attainable perfection, what are we next to attempt? Are we and our posterity to spin and weave, build ships, and speculate in commerce, as the highest occupations to which human nature can aspire, and persevere in these labours till the end of time? If not, who shall guide the helm in our future voyage on the ocean of existence? and by what chart of philosophy shall our steersman be directed?

The British are here cited as a type of mankind at large; for in every age and every clime, similar races have been run, with similar conclusions. Only one answer can be returned to these inquiries. Man is, apparently, a progressive being; and the Creator, having designed a higher path for him than for the lower creatures, has given him intellect to discover his own nature and that of external objects, and left him, by the exercise of that intellect, to find out for himself the method of placing his faculties in harmony among

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE 11

themselves, and in accordance with the external world. Time and experience are necessary to accomplish these ends; and history exhibits the human race only in a state of progress towards the full development of its powers, and the attainment of rational enjoyment.

As long as man remained ignorant of his own nature, he could not, of design, form his institutions in accordance with it. Until his own faculties and their relations became the subjects of his observation and reflection, they operated as mere blind impulses. Apparently he adopted savage habits, because, at first, his animal propensities were not directed by the moral sentiments, or enlightened by reflection. He next assumed the condition of the barbarian, because his higher powers had made some advance, but had not yet attained supremacy; and he now devotes himself, in Britain, to commerce and manufactures, because his constructive faculties and intellect have given him power over physical nature, while his love of property and ambition are predominant, and are gratified by such avocations. Not one of these conditions, however, has been adopted from design, or from perception of its suitableness to the whole nature of man. He has been ill at ease in them all; but it does not follow that he must continue for ever equally ignorant of his nature, and equally incapable of framing institutions in harmony with it. The simple facts, that the Creator has bestowed on man reason, capable of discovering his own nature, and its relations to external objects; that He has left him to apply it in framing suitable institutions to ensure his happiness; that, nevertheless, man has hitherto been ignorant of his nature and of its relations; and that, in consequence, his modes of life have never been adopted from enlightened views of

[page] 12 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

his whole qualities and capacities, but have sprung up from the impulsive ascendancy of one blind propensity or another,—warrant us in saying, that a new era will begin, when man shall study his constitution and its relations with success; and that the future may exhibit him assuming his station as a rational creature, pursuing his own happiness with intelligence and design, and at length attaining to higher gratification than any which he has hitherto enjoyed.

In the next place, the inquiry naturally occurs, what has been the cause of the human race remaining for so many ages unacquainted with their own nature and its relations? The answer is, that, before the discovery of the functions of the brain, it was impossible to reach a practical philosophy of mind. The philosophy of man was cultivated as a speculative and not as an inductive science; and even when attempts were made at induction, the manner in which they were conducted was at variance within the fundamental requisites of a sound philosophy.* Consequently, even the most enlightened nations have never possessed any true philosophy of mind, but have been bewildered amidst innumerable contradictory theories.

This deplorable condition of the philosophy of human nature is strikingly and eloquently described by Mons. de Bonald, in a sentence translated by Mr Dugald Stewart, in his Preliminary Dissertation to the Encyclopædia Britannica: "Diversity of doctrine," says he, "has increased from age to age, with the number of masters, and with the progress of knowledge; and Europe, which at present possesses libraries filled with philosophical works, and which reckons

* See System of Phrenology. Fifth Edition, p. 58.

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 13

up almost as many philosophers as writers; poor in the midst of so much wealth, and uncertain, with the aid of all its guides, which road it should follow; Europe, the centre and focus of all the lights of the world, has yet its philosophy only in expectation."

While Philosophy has continued in this unprofitable condition, Religion also has failed to enter into harmonious alliance with the order of nature. Science has banished from the minds of well educated individuals belief in the exercise, by the Deity, in our day, of special acts of supernatural power, as a means of influencing human affairs. Men now act more on the belief that this world's administration is conducted on the principle of an established order of nature, in which objects and agencies are presented to man for his study, are to some extent placed under the control of his will, and wisely calculated to promote his instruction and enjoyment. The creed of the modern man of science is well expressed by Mr Sedgwick in the following words:—"If there be a superintending Providence, and if His will be manifested by general laws, operating both on the physical and moral world, then must a violation, of these laws be a violation of his will, and be pregnant with inevitable misery. Nothing can, in the end, be expedient for man, except it be subordinate to those laws the Author of Nature has thought fit to impress on his moral and physical creation." Other clergymen also embrace the same view. The Rev. Thomas Guthrie In his late admirable pamphlet, "A Plea for Ragged Schools," observes, that, "They commit a grave mistake, who forget that injury as inevitably results from Lying in the face of a moral or mental, as of a physical law."

Nevertheless, the natural order of providence is very

[page] 14 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

meagrely taught by the masters in theology to their followers, as of divine authority, and as regulating this world's affairs. I put the following questions in all earnestness. Are the fertility of the soil, the health of the body, the prosperity of individuals and of nations,—in short, the great secular interests of mankind, now governed by special acts of supernatural power? Science answers that they are not. Are they then governed by any regular and comprehensible natural laws? If they are not, then is this world a theatre of anarchy, and consequently of atheism,—it is a world without the practical manifestation of a God. If, on the other hand, as science shews, such laws exist, they must be of divine institution, and worthy of all reverence; and I ask, In the standards of what church, from the pulpits of what sect, and in the schools of what denomination of Christians, are these laws taught to either the young or old as of divine authority, and as practical guides for conduct in this world's affairs? If we do not now experience a special supernatural government of the world, but a government by natural laws; and if these laws are not studied, honoured, and obeyed, as God's laws, are we not actually a nation without a religion in harmony with the true order of Providence; and, therefore, without a religion adapted to practical purposes?

The answer will probably be made—that this argument is rank infidelity; but, with all deference, I reply that the denial of a regular, intelligible, wisely adapted, and divinely appointed order of nature, as a guide for human conduct in this world, is downright atheism; while the acknowledgement of the existence of such an order, accompanied by the nearly universal neglect of teaching and obeying its requirements, is true, practical, baneful infidelity, disrespectful to God, and injurious

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE 15

to the best interests of man. Let those, therefore, who judge us, take care that they be not judged; and let those who think that they stand, take heed lest they fall. The public mind is opening to such views as I am now unfolding; and they must in future be met by other arguments than cries of irreligion, and appeals to bigotry and passion.

There must be a cause for this untoward state of the relationship between religion and science, and it appears to me to be the following. The popular theology was elaborated in the very dawn of civilization, when little was known scientifically either of the philosophy of the human mind, or of the laws which govern the natural world, and, in consequence of thus ignorance, it was a difficult task to form a theology in harmony with both. The greater number of philosophers and divines, having failed to discover a consistent order of administration in the moral world, rashly concluded that none such exists, or that it is inscrutable by human intelligence. The churches which have at all recognised the order of nature, have attached to it a lower character than truly belongs to it. They have treated science and secular knowledge chiefly as objects curiosity and sources of gain; and have given to actions intelligently founded on them, the character of prudence. So humble has been their estimate of the importance of science, that they have not systematically called in the influence of the religious sentiments to hallow, elevate, and enforce the teachings of nature. In most of their schools the elucidation of the relations of science to human conduct is omitted altogether, and catechisms of human invention usurp its place.

Society, meantime, proceeds in its secular enterprises

[page] 16 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

on the basis of natural science, so far as it has been able to discover it. If practical men send a ship to sea, they endeavour to render it stanch and strong, and to place in it an expert crew and an able commander, as conditions of safety, dictated by their conviction of the order of nature in flood and storm. If they are sick, they resort to a physician to restore them to health, according to the ordinary laws of organization. If they suffer famine from wet seasons, they drain their lands; and so forth. All these practices and observances are taught and enforced by men of science and the secular press, as measures of practical prudence; but few churches recognise the order of nature on which they are founded, as a becoming subject of religious instruction.

Nevertheless, the relation between religion and science has continued to constitute an interesting and important subject of investigation. The late Earl of Bridgewater died in February 1829, and left the sum of L.8000, which, by his will, he directed the President of the Royal Society of London to apply in paying any person or persons to be selected by him, "to write, print, and publish one thousand copies of a work 'On the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God, as manifested in the Creation;' illustrating such work by all reasonable arguments, as, for instance, the variety and formation of God's creatures in the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms; the effect of digestion, and thereby of conversion; the construction of the hand of man, and an infinite variety of other arguments; as also by discoveries, ancient and modern, in arts, sciences, and the whole extent of literature." The President of the Royal Society called in the aid of the Archbishop of Canterbury and of the Bishop of London, and with

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 17

their advice nominated eight gentlemen to write eight treatises on different branches of this great subject.

One of the objects of the Earl of Bridgewater appears to have been to ascertain what the character of external nature and the capacities of the human mind really are, and what is the adaptation of the one to the other; questions of vast importance in themselves, and which can be solved only by direct, bold, and unbiassed appeals to nature. This subject was committed to Dr Chalmers.

In the execution of this object, the first inquiry should have been, " What is the Constitution of the human mind ?" because, before we can successfully trace the adaptation of two objects to each other, we must be acquainted with each separately. But Dr Chalmers and all the other authors of the Bridgewater Treatises have neglected this branch of inquiry. They disdained to acknowledge Phrenology as the philosophy of mind, yet they have not brought forward any other. Indeed they have not attempted to assign to human nature any definite or intelligible constitution. In consequence, they appear to me to have thrown extremely little new light on the moral government of the world.

In the following work, the first edition of which was published in 1828, before the Earl of Bridgewater's death, I have endeavoured to avoid this inconsistency. Having been convinced, after minute and long-continued observation, that Phrenology is the true philosophy of mind, I have assumed it as the basis of my reasoning in this inquiry, it is indispensably necessary to adopt some system of mental philosophy, in order to obtain one of the elements of the comparison; but if he choose, may regard the phrenological hypothetical, and judge of them by the result.

B

[page] 18 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

Or he may attempt to substitute in their place any better system with which he is acquainted, and try how far it will enable him successfully to proceed in the investigation.

In the next place, in instituting the comparison in question, I have brought into view, and endeavoured to substantiate and apply, a doctrine, which, so far as I have yet been able to discover, is the key to the true theory of the divine government of the world, but which has not hitherto been duly appreciated,—namely, the independent existence and operation of the natural laws of creation. The natural laws may be divided into three great classes,—Physical, Organic, and Moral; and the peculiarity of the new doctrine is, its inculcating that these operate independently of each other; that each requires obedience to itself; that each, in its own specific way, rewards obedience and punishes disobedience; and that human beings are happy in proportion to the extent to which they place themselves in accordance with all the divine institutions. For example, the most pious and benevolent missionaries sailing to civilize and Christianize the heathen, may, if they embark in an unsound ship, be drowned by disobeying a physical law, without their destruction being averted by their morality. On the other hand, if the greatest monsters of iniquity were embarked in a stanch and strong ship, and managed it well, they might, and, on the general principles of the government of the world, they would, escape drowning in circumstances exactly similar to those which would send the missionaries to the bottom. There appears something inscrutable in these results, if only the moral qualities of the men be contemplated; but if the principle be recognised, that ships float in virtue of a purely physical law,—and that

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 19

the physical and moral laws operate independently, each in its own sphere,—the consequences appear in a totally different light.

In like manner, the organic laws operate independently; and hence, one individual who has inherited a sound bodily constitution from his parents, and observed the rules of temperance and exercise, will enjoy robust health, although he may cheat, lie, blaspheme, and destroy his fellow-men; while another, if he have inherited a feeble constitution, and disregarded the laws of diet and exercise, will suffer pain and sickness, although he may be a paragon of every Christian virtue. These results are frequently observed; and on such occasions the darkness and inscrutable perplexity of the ways of Providence are generally moralised upon; or a future life is called in as the scene in which these crooked paths are to be rendered straight. But if my views be correct, Divine wisdom and goodness are abundantly conspicuous in these events; for by this distinct operation of the organic and moral laws, order is preserved in creation, and, as will afterwards be shewn, the means of discipline and improvement are afforded to all the human faculties.

The moral and intellectual laws also have an independent operation. The man who cultivates his intellect and higher sentiments, and who habitually obeys the precepts of Christianity, will enjoy within himself a fountain of moral and intellectual happiness, which appropriate reward of that obedience. He will also become more capable of studying, comprehending, and obeying, the physical and organic laws;—of lacing himself in harmony with the order of creation; of attaining the highest degree of perfection, reaping the greatest extent of happiness, of which

[page] 20 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

his nature in this world is susceptible. In short, whenever we apply the principle of the independent operation of the natural laws, the apparent confusion of the moral government of the world is greatly diminished. These views will be better understood and appreciated after perusing the subsequent chapters, the object of which is to unfold and apply them; the aim of these introductory remarks being merely to prepare the reader for travelling over the more abstruse portions of the work with a clearer perception of their scope and tendency. Before proceeding, however, I beg to observe that some obscurity, which it is proper to remove, occasionally attends the use of the words, 'Laws of nature.' A law of nature is not an entity distinct from nature. The atoms or elements of matter act invariably in certain definite manners in certain circumstances; the human mind perceives this regularity, and calls the action characterised by it, action according to law. But the term "law," thus used, expresses nothing amore than the mind's perception of the regularity. The word does not designate the efficient cause of the action; yet many persons attach a meaning to the term, as if it implied causation. The cause of the regularity which we observe in the motions and reciprocal influences of matter, may be supposed to be either some quality inherent in the atoms, or certain powers and tendencies communicated to them by the Divine Mind, which adapts and impels them to all their modes of action. This last is the sense in which I understand the subject, and I coincide in the views expressed in an article in the Edinburgh Review,* generally ascribed to the Rev. Mr Sedgwick.

* Vol. lxxxii., p. 62, July 1845.

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE.21

"What know we," says he, "of the God of nature (we speak only of natural means), except through the faculties He has given us, rightly employed on the materials around us? In this we rise to a conception of material inorganic laws, in beautiful harmony and adjustment; and they suggest to us the conception of infinite power and wisdom. In like manner we rise to a conception of organic laws—of means (often almost purely mechanical, as they seem to us, and their organic functions well comprehended) adapted to an end—and that end the well-being of a creature endowed with sensation and volition. Thus we rise to a conception both of Divine Power and Divine Goodness; and we are constrained to believe, not merely that all material law is subordinate to His will, but that He has also (in the way He allows us to see His works) so exhibited the attributes of His will, as to shew himself the mind of man as a personal and superintending God, concentrating His will on every atom of the universe."

I add that, in adopting Mr Sedgwick's phrase of "a personal God," I use the word "person," according Locke's definition of it, "a thinking, intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and considers itself as itself, the same thinking thing in different times and places." In this sense of the word, our faculties enable us to assign a personal character to the Deity, without presuming to form any opinions concerning His form, His substance, or His mode of being.

These views have now been submitted for twenty years to public consideration, in the present work, and recently in my "Lectures on Moral Philosophy," to which I beg leave to refer. The only plausible objection which I have seen stated to the general doc-

[page] 22 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

trine contained in them, is, that circumstances occasionally occur in which it is virtuous to set the physical and organic laws at defiance;—as when a man rushes into the water to rescue a drowning fellow-creature, or on a railroad-track, in order to remove from it a child or deaf or blind person, who, but for such assistance, would be smashed to pieces by an advancing train. The benevolent agents in such enterprizes occasionally lose their own lives, either saving, or not, those of the objects of their generous care; and it is argued, that in these instances, we applaud the self-devotion which set at nought the physical action of the waves and the train, and risked life to perform a disinterested act of humanity. But these cases afford no real exceptions to the doctrine which I have maintained, that even virtuous aims do not save us from the consequences of breaking the natural laws. A few explanations will, I hope, remove the difficulty apparently presented by these and similar instances. Unless the benevolent actors in these enterprizes are able successfully to encounter the waves and escape the train, there is little chance of their realizing their generous intentions or gaining the objects of their solicitude. Obedience to the physical laws until they succeed is indispensable, otherwise both they and their objects will perish, and the calamity will thereby be aggravated. If they save the object, but die themselves, there is no gain to society, but the contrary; the life lost is most probably more valuable than the one saved.

No man, therefore, is justifiable in leaping into the water even to rescue a fellow-creature, unless he be confident that, by his skill in swimming, or by mechanical aid at his command, he can comply with the physical law which regulates floatation. If he do go into the

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 23

flood deliberately, and in the consciousness that he cannot comply with the conditions of that law, he commits suicide. If, under the impulse of generous emotion, he plunges into the water, miscalculating his power, and is overcome; although we may admire and applaud his humane intention, we must lament the mistake he made in the estimate of his own ability. In the case of the railway train, if the generous adventurer, after removing his fellow-creature from the rail, is himself overtaken by the engine and killed; while we give the tribute of our esteem to his humanity, we must regret his miscalculation. In no case is it possible to set the physical laws at defiance with impunity. Cases, such as those before alluded to, may occur, in which it may be justifiable to risk the sinister influence of a physical or organic law for the sake of a moral object of paramount importance; but even in such instances we are bound to use every possible precaution and effort to obey those laws; because our success in attaining the object pursued will depend on the extent of our obedience. We cannot escape their influence, if we do infringe them, and, assuming that we save a fellow-creature, if we perish ourselves, we shall have only half attained our aim.

The objection to the doctrine of the natural laws, therefore, founded on these cases, appears to me to arise from a misunderstanding of the sense in which I use the word "punishment." The dictionary definition punishment is "infliction imposed in vengeance of a crime;" but this is not my meaning. The inflictions under human laws have no natural, and therefore no necessary, relation to the offence they punish. There is no natural relation, for example, between stealing and mounting the steps of a tread-mill. When, there-

[page] 24 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

fore, I am represented as teaching that, in these instances, the benevolent agent is "punished" with the loss of life, for acting under the impulse of his moral emotions, those who understand the word "punish" in the dictionary sense, are shocked, and reject the doctrine as unsound. But the difficulty disappears when the word is differently defined. By punishment, I mean the natural evil which follows the breach of each physical, organic, and moral law. I regard the natural consequence of the infraction, not only as inevitable, but as pre-ordained by the Divine Mind, for a purpose: That purpose appears to me to be to deter intelligent beings from infringing the laws instituted by God for their welfare, and to preserve order in the world. When people, in general, think of physical laws, they perceive the consequences which they produce to be natural and inevitable; but they do not sufficiently reflect upon the intentional pre-ordainment of these consequences, as a warning or instruction to intelligent beings for the regulation of their conduct. It is the omission of this element that renders the knowledge of the natural laws, which is actually possessed, of so little use. The popular interpretations of Christianity have thrown the public mind so widely out of the track of God's natural providence, that His object or purpose in this pre-ordainment is rarely thought of; and the most flagrant, and even deliberate infractions of the natural laws, are spoken of as mere acts of imprudence, without the least notion that the infringer is contemning a rule deliberately framed for his guidance by Divine wisdom, and enforced by Divine power.

In considering moral actions, on the contrary, the public mind leaves out of view the natural and inevitable. Being accustomed to regard human punishment

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 25

as arbitrary, and capable of abeyance or alteration, it views in the same light the inflictions asserted to take place under the natural moral law, and does not perceive divine pre-ordainment and purpose in the natural consequences of such moral actions. The great object which I have had in view in the present work is to shew that this notion is erroneous; and that there is a natural preordained consequence, which man can neither alter nor evade, attached to the infringement of every natural law.

To express this idea correctly, a term is required, something between simple "consequence" and "punishment." The former fails to convey my idea in its totality, and the latter adds something to distort it. I find it difficult to discover an appropriate word ; but hope that this explanation will render the idea itself comprehensible.

I have endeavoured to present the administration of the present world in a light calculated to arrest attention, and to draw towards it that degree of consideration to which it is justly entitled. This proceeding will be recognised as the more necessary, if one principle, largely insisted on in the following pages, shall be admitted to be sound, viz., that religion operates on the human mind, in subordination, and not in contradiction, to its natural constitution. If this view be well-founded, it will be indispensable that all the natural conditions required by the human constitution as preliminaries to moral and religions conduct be complied with, before any purely religious teaching can produce its full effects. If, for example, an ill-constituted brain be unfavourable to the appreciation and practice of religious truth, it is not an unimportant inquiry, whether any, and what, influence can be exer-

C

[page] 26 GENERAL VIEW OF THE

cised by human means in improving the size and proportions of the mental organs. If certain physical circumstances and occupations,—such as insufficient food and clothing, unwholesome workshops dwelling-places and diet, and severe and long-protracted labour,—have a natural tendency, in consequence of their influence on the nervous system in general, and the brain in particular, to blunt all the higher feelings and faculties of the mind, and if religious emotions cannot be experienced within full effect by individuals so situate, the ascertainment, with a view to removal, of the nature, causes, and effects of these impediments to holiness, is not a matter of indifference. This view has not been systematically adopted and acted on by the religious instructors of mankind in any age, or any country and, in my humble opinion, for this sole reason, that the state of moral and physical science did not enable them either to appreciate its importance, or to carry it into effect. By presenting Nature in her simplicity and strength, a new impulse and direction may perhaps be given to their understandings; and they may be induced to consider whether their universally confessed failure to render men as virtuous and happy as they desired, may not, to some extent, have arisen from their non-fulfilment of the natural conditions instituted by the Creator as preliminaries to success. They have complained of war waged, openly or secretly, by philosophy against religion; but they have not duly considered whether religion itself warrants them in treating philosophy and all its dictates with neglect in their instruction of the people. True philosophy is a revelation of the Divine Will manifested in creation; it harmonizes with all truth, and cannot with impunity be neglected.

[page] CONSTITUTION OF HUMAN NATURE. 27

If we can persuade the people that the course of nature, which determines their condition at every moment of their lives, "is the design-law-command-instruction (any word will do), of an all-powerful, though unseen Ruler, it will become a religion with them; obedience will be felt as a wish and a duty, an interest and a necessity." The friend from whose letter I quote these words, adds, "But can you persuade mankind thus? I mean, can you give them a practical conviction?" I answer—In the present unsatisfactory condition of things, the experiment is, at least, worth the trying; not with a view to questioning the importance of Scripture teaching; but for the purpose of communicating to its precepts in relation to practical conduct in this world, a basis also in nature, and investing the ordinary course of providence within that degree of sanctity and reverence which can be conferred on it only by treating it as designedly calculated to instruct, benefit, and delight, the whole faculties of man.

28 ON NATURAL LAWS.

CHAPTER I.

ON NATURAL LAWS.

In natural science, three subjects of inquiry may be distinguished : 1st, What exists? 2dly, What is the use of what exists? and, 3dly, Why was what exists constituted such as it is ?

It is matter of fact, for instance, that arctic regions and the torrid zone exist,—that a certain kind of moss is abundant in Lapland in winter,—that the rein-deer feeds on it, and enjoys health and vigour in situations where most other animals would die; that camels exist in Africa,—that they have broad hoofs, and stomachs fitted to retain water for a considerable time,—and that they flourish amid arid tracts of sand, where the rein-deer would hardly live for a day. All this falls under the inquiry, What exists ?